Embracing a Nonlinear Narrative Structure

When I set out to write a story about climate change, I got about fifty pages in and felt the spark sputter and die out. For the longest time, I sat there, watching the spiral of gray smoke. I had thought a solitary protagonist, Eleanor, could carry the story, crawling through the obstacle course of a traditional plot, utterly altered by the end. But it felt flat and tired and dishonest.

Why was I surprised? How could the hardest thing humans have ever faced be rendered with one character? Sometimes, narrative artifice is so far from truth that it becomes paralyzing.

Still, I felt the urgency to figure it out. For years, my scientist friends have said they need stories about the climate crisis and that mere information alone is insufficient to spur changes in behavior, especially when the destruction is unfolding at an alarming pace. But kind of what story? How to tell it?

Rebecca Solnit echoed this in a recent Guardian article, “Every crisis is in part a storytelling crisis. This is as true of climate chaos as anything else. We are hemmed in by stories that prevent us from seeing, or believing in, or acting on the possibilities for change.”

The answer was elusive until I reread Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1986 essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” In this profound piece, she calls for stories other than the hero’s journey. She reminds us that before the spear, the primary tool was the carrier bag. Humans gathered nuts, seeds, roots, sprouts, shoots, and berries, adding bugs and mollusks and netting or snaring birds, fish, rats, rabbits, and other tuskless small fry to up the protein. Mostly women did this gathering and carrying, along with children hammocked on their backs. Yes, the story of spear-throwing and hunting animals was thrilling, with blood and battle, but it left out vast swathes of life experience: the gathering story.

A gathering story, I thought, isn’t about one protagonist but a group of people collecting, working together, solving something—food supply, survival, the climate crisis. It’s the oldest story, though most of us have forgotten it. it wouldn’t be easy, I was stuffed with the hero journey story. Le Guin warned about this: “It’s unfamiliar, it doesn’t come easily, thoughtlessly to the lips as the killer story does.”

To experience one possible shape of a baggier story, I read Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century novel, The Decameron, 100 tales told by seven women and three men, unified by the theme of love. I read The Feast of Love by Charles Baxter, who was influenced by Boccaccio; Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann; There There, by Tommy Orange, who was influenced by McCann; and The Overstory by Richard Powers.

I learned from John Gardner in The Art of Fiction that the design of these bag-like stories has a name: thematic juxtaposition. A story can be created by putting characters and incidents in relationships, not causally but thematically.

After that, other characters arrived quickly. Eleanor’s daughter, Ava, a scientist working to solve the massive plastic problem, grapples with whether to have a child. Eleanor’s son, Ed, is a ballet dancer who, for an art performance, is attempting to inhabit the consciousness of a rat. A young boy, Lincoln, wants to bring the natural world to his bleak urban neighborhood. A middle-aged woman, Lucinda, prefers to be in the company of dogs to humans and spends all her extra time volunteering at the humane society.

Like a long thread, Eleanor weaves in and out of most of these other stories, which began to take the shape of a short story collection (though I still think of it as a bag.) But Eleanor’s stories ended differently than traditional short stories. They were far more open, like a window letting in the wind. Seventy years old, an environmental economist, she devoted her life to convincing companies to do the right thing. She learned the corporate language, capitalism’s language, arguing that the right thing—clean air, clean water, sustainable practices—benefited the bottom line. “Growing old has brought the inevitable, the body working furiously at demolition; she knew she would not escape that. But she wasn’t prepared to experience it at the same time as the planet’s demise.”

After the first draft, I wondered if I should fix her stories and make them feel more like short stories. But then, I thought, no, she’s like a bag, waiting and hoping for something other than grief to fill her being. She is, as we all are, a human in the world, and her stories leave the door open for something to come in and lift her out of her grief-stricken place. Or for her to step out and encounter something, someone to lift her.

This is part of the book’s design, too. With enough characters and different voices—including Nature’s voice—it’s an open bag for readers to step in and find laughter and sorrow and rays of hope.

—

Nina Schuyler’ s novel, Afterword, was published in 2023. Her novel, The Translator, won the Next Generation Indie Book Award for General Fiction and was shortlisted for the William Saroyan International Writing Prize. Her novel, The Painting, was shortlisted for the Northern California Book Award. Her nonfiction book, How to Write Stunning Sentences, is a bestseller. She teaches creative writing for Stanford Continuing Studies and the University of San Francisco. She lives in California.

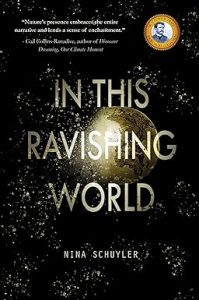

IN THIS RAVISHING WORLD

In this Ravishing World is a sweeping, impassioned short story collection, ringing out with joy, despair, and hope for the natural world. Nine connected stories unfold, bringing together an unforgettable cast of dreamers, escapists, activists, and artists, creating a kaleidoscopic view of the climate crisis. An older woman who has spent her entire life fighting for the planet sinks into despair.

In this Ravishing World is a sweeping, impassioned short story collection, ringing out with joy, despair, and hope for the natural world. Nine connected stories unfold, bringing together an unforgettable cast of dreamers, escapists, activists, and artists, creating a kaleidoscopic view of the climate crisis. An older woman who has spent her entire life fighting for the planet sinks into despair.

A young boy is determined to bring the natural world to his bleak urban reality. A scientist working to solve the plastic problem grapples with whether to have a child. A ballet dancer endeavors to inhabit the consciousness of a rat. In this Ravishing World is a full-throated chorus— with Nature joining in— marveling at the exquisite beauty of our world, and pleading, raging, and ultimately urging all of its inhabitants toward activism and resistance.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing