Females on ships in the age of sail – from women dressed as men to lone travellers

My second novel, SONG OF THE SEA MAID, is set in the mid-C18th and my main character Dawnay Price needs to travel in order to do what she wants to do. She is a scientist – or as they’d say in those days, a natural philosopher – and she wants to study the flora and fauna of islands. She can’t do that from her front room. As she says, “a true discoverer must study their subject in situ… I simply must travel.”

My second novel, SONG OF THE SEA MAID, is set in the mid-C18th and my main character Dawnay Price needs to travel in order to do what she wants to do. She is a scientist – or as they’d say in those days, a natural philosopher – and she wants to study the flora and fauna of islands. She can’t do that from her front room. As she says, “a true discoverer must study their subject in situ… I simply must travel.”

When I was planning my story, I knew that Dawnay would go abroad, but then I realised I had no idea how she’d get there. For narrative reasons, it was important she did not have a companion. So, how did unaccompanied women travel abroad in the C18th? I set myself to find out.

Four books came in useful. The first I found randomly in a second-hand bookshop in Horncastle. It was called ‘The Wynne Diaries’ (ed. Anne Fremantle) and was a very entertaining account of two well-to-do sisters travelling on board various ships in Napoleonic Europe. It was a bit late for my setting (Dawnay travels in the 1750s), but I wanted to understand what life on a ship was like for an 18th-century woman.

As it turned out, though it was a delightful book, much of their time was spent looking for husbands at parties, with very little information about life on board ship for more ordinary people. It did however teach me some lovely C18th turns of phrase, such as “every time we take a walk we carry home our pockets full of impertinences which the peasants bestow upon us”!

So, I decided next to look into women who took a bit more of an active role on ships. I found a fascinating book about women in the age of sail: ‘Female Tars’ by Suzanne J. Stark. This brilliant piece of revelatory history begins with chapters on Prostitutes and Seamen’s Wives and Women of the Lower Deck, detailing the extraordinarily hard lives many working class women suffered on board ship both in port and at sea.

So, I decided next to look into women who took a bit more of an active role on ships. I found a fascinating book about women in the age of sail: ‘Female Tars’ by Suzanne J. Stark. This brilliant piece of revelatory history begins with chapters on Prostitutes and Seamen’s Wives and Women of the Lower Deck, detailing the extraordinarily hard lives many working class women suffered on board ship both in port and at sea.

And it goes on to examine cases of women who dressed as men in order to join the Navy, some of these women going along quite happily undiscovered for years. It turns out nobody washed very often, thus few opportunities for anyone to notice that there was something missing down their breeches…

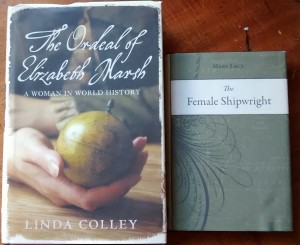

This led me to a marvellous find: ‘The Female Shipwright’, written by Mary Lacy, a real life cross-dressing sailor, whose autobiography was first published in 1773 and is still available to read today. It not only gave me some wonderful uses of language – such as “cut their cables”; “great and boisterous seas” and “put a hand to the staysail braces, and help to hale them up” – but also gave me a wonderful insight into the male environment on board ship; in fact, the male-dominated nature of most foreign travel in those days and how it was a task that carried with it some danger and certainly apprehension for many females who wished to travel.

My character, though, was not to be a sailor dressed in men’s clothing – although I could not resist the idea of it and did have one of my other characters mention the true case of a woman who followed her husband to war in the army, dressed as a man and served for some time before an injury revealed her secret.

Dawnay reflects upon this as the height of excitement, when she hears of it as a girl, but the soldier who tells her makes the point that it “must be a tricky thing to lie all the time, every day, and to live that lie”. Thus, the difficulty of being a woman in a man’s world.

All three of these books gave me priceless information, not only about ships, yet also the limitations placed upon women at that time and the sometimes ingenious and often brave ways in which women sought to circumvent them. Despite objection, Dawnay does manage to fulfil her plan of travelling alone aboard ship to Portugal and onwards into the Mediterranean.

I had heard mention of accounts of unaccompanied women on such voyages, so I felt that Dawnay’s travels had basis in historical fact. But it wasn’t until I’d actually finished the novel that I was recommended another great book about an intrepid woman of this age: ‘The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A Woman in World History’ by Linda Colley.

I had heard mention of accounts of unaccompanied women on such voyages, so I felt that Dawnay’s travels had basis in historical fact. But it wasn’t until I’d actually finished the novel that I was recommended another great book about an intrepid woman of this age: ‘The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A Woman in World History’ by Linda Colley.

This is the true story of a prolific traveller, in whose extraordinary yet largely unknown lifetime she crossed the oceans with seeming ease; indeed, one of her greatest adventures was when she travelled alone aboard ship only to be captured by Moroccan pirates and presented to the Sultan.

I realised that in my own character’s battles to be freed of the restrictions of her age, Dawnay was not alone, and had the hidden histories of other courageous women to keep her company in that sometimes lonely yet often liberating space.

—

Rebecca Mascull

Rebecca Mascull is the author of two novels published by Hodder and Stoughton. THE VISITORS is the story of Adeliza Golding, a deaf-blind girl living on her father’s hop farm in Victorian Kent; it was nominated for the Edinburgh Festival First Book Award. SONG OF THE SEA MAID follows Dawnay Price, an eighteenth century orphan who becomes a scientist and makes a remarkable discovery. Rebecca lives by the sea in the east of England with her partner Simon, their daughter Poppy and cat Tink. She has worked in education and has a Masters in Writing.

http://rebeccamascull.tumblr.com/

https://twitter.com/rebeccamascull

https://www.facebook.com/RebeccaMascull

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing