How I Wrote an Historical Novel Set in China

It seems that China has always beckoned to me. The process involved in writing my novel, The Secret Language of Women, Book #1 of the Wayfarer Trilogy, began way before I ever thought of becoming a writer. I was a child growing up in Brooklyn and became entranced by the Chinese family who owned the shop near my grandparents’ house.

It seems that China has always beckoned to me. The process involved in writing my novel, The Secret Language of Women, Book #1 of the Wayfarer Trilogy, began way before I ever thought of becoming a writer. I was a child growing up in Brooklyn and became entranced by the Chinese family who owned the shop near my grandparents’ house.

They offered me a curious fruit—dried lychee—whenever we dropped off my father’s shirts to be laundered. The fruit was dark and soft, but not until many years later would I discover the fresh, fleshy fruit is white and moist.

As a girl, my maternal grandfather told me stories of being in the Italian Navy, traveling the waterways of China and fighting as a sailor during the Boxer Rebellion at the turn of the 19th Century. Grandpa’s narratives were about diminutive Oriental girls with hair the color of jet, European navies, ships and battles. How exotic and alluring!

I’m blessed with a vivid imagination and as he reminisced, I pictured his anecdotes of sailors brawling with other sailors from various foreign nations, and sailors fighting Boxers. He spoke of life in Sicily before voyaging all over China and his time in Shanghai.

Fascinated by these tales, his recollections beguiled me. I saw his passport picture in uniform—young and handsome, a virile man with a big moustache—no wonder my grandmother fell in love with him. His occupation was listed as a fisherman. Even that charmed me.

With this acquired wealth of knowledge, I knew someday I’d visit China and perhaps write a story about gods, tattoos, dragons, statues of Buddha, temples, the tea ceremony, calligraphy, karma, and acupuncture.

What good fortune to be married to a world traveler who afforded me several trips to Asia and China, where I did on location and in-depth research! China’s landscape is magnificent, and when I travelled on the Yangtze River to the Three Gorges, I felt an instant kinetic connection with the past and my grandfather.

In China, I became enchanted by Beijing, formerly Peking, which held Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City. I fell in love with the city of Guilin, a painter’s paradise surrounded by magnificent mauve hills and cliffs, waterways and markets, and used this as the birthplace of my main character Lian.

China enthralled me, and I surrendered to its spellbinding history, culture, superstitions, art, cuisine, medicine. I learned about Nüshu, the secret language women communicated in, now extinct, like the binding of female children’s feet.

Later, I culled from all of these stimuli surrounding me and which I absorbed into a personal aesthetic and part of my very being. These persuasive influences, I used in my novel-writing. Returning from Asia equipped with travel notes, I began a romantic story in alternating chapters, incorporating China’s historical details, using the Boxer Rebellion as backdrop. I had paid attention and there was going to be a pay-off.

My horoscope predicted I’d write a novel. I was born in the Year of the Horse. So after I’d completed my MFA in Creative Writing at Florida International University, I began writing my historical literary novel The Secret Language of Women. The kernel of the novel was a short story, entitled “The Rain,” which I’d written as part of my thesis in Grad school at FIU. This collection of short stories was published as The Other Side of the Gates. To this revised short piece, I added material based on family stories converted into fiction. I had learned the art of listening while young, and coupled with that tool, I merged intense and ferocious reading and my love of cinema.

I not only read Asian-American writers such as Ha Jin, Amy Tan, Lisa See, Anchee Min, Pearl S. Buck, but a host of Chinese authors in translation: Hua Yu, Gao Xingjian, Gelling Yan. I read fiction and biography by American and British authors set in China for theme and scene, and I read historical novels for structure. I watched a host of Chinese films repeatedly: Raise the Red Lantern, Crouching Tiger, Flying Dragon, Farewell My Concubine, Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl, The Flowers of War and many others.

I listened, I read. I watched. And so I began to write a story in a third person male POV. I researched and described a ship that would have been in China during that epoch. For a workshop I was about to take in the University of Iowa’s summer program, I had to write twenty pages. I didn’t want to hand in anything already written—here was a golden opportunity to plunk down something new. I literally dashed down twenty-two pages in the first person POV of a fictitious, bi-lingual woman whom my fictional character, loosely based on my Grandpa, would fall in love with.

It didn’t hurt that I’m fluent in Italian and Spanish and love to fling foreign words into my fiction and poetry. I studied many Mandarin expressions for chapter headings and to disperse throughout the novel to give it authenticity, and my friend Guo Liang, who is from Beijing, made sure these were correct. I also sent an early draft to his friend, Dawn Li, who is also bilingual.

For the workshop, I assigned the name Giacomo for my sailor, and Lian for the main character—I’d found my protagonist and the female perspective I needed. When I realized the main character would be a woman, the writing flowed. It wasn’t forced and came naturally.

Next, when I returned home, I researched and added exciting scenes—writing about subjects and topics I’d never dared to consider writing before: abandonment, abortion, rape. All difficult themes for me, but I wanted and needed a challenge. Another thought-provoking skill I acquired during the writing was using people who had actually lived during this era—the Empress CiXi and the priest Alberico Crescitelli.

I also included my horoscope sign and wrote important scenes for a horse. I love horses and they appear in all of my novels. One caveat I learned well and should serve for all writers: be careful not to get stuck in the research. Remember, writers write, and make the research appear seamless.

Although I certainly don’t know if any of my story was part of my Grandpa’s living existence in China, it made me ponder and pursue a line of thinking from which I fashioned into a strong plot. Of course being a poet, I included poetry and lyrical writing because I feel this is where my strength lies.

I re-read my friend and mentor John Dufresne’s nonfiction books: The Lie That Tells a Truth and Is Life Like This?—on how to write a first novel draft in six months, a refresher course of what John had taught me at FIU. I started a notebook into which I jotted down things like links to Google sites, Chinese words and English translations, Chinese poets, lines of poems, names of characters, lists of character attributes and traits, foods, drinks, names of places and rivers, notes on the Boxer Rebellion, the Empress CiXi, Opium Wars, Chinese herbs, medicines, and acupuncture.

I wrote a first draft of The Secret Language of Women sketching back story, themes, motifs, metaphors, settings, dialogue, obligatory scenes, character motivation, conflict, cause and effect, climax, resolution and denouement. I have never been successful with writing outlines and the plot developed and germinated out of the story. This was the exhilarating, creative part, next would come the cerebral part—revision. I revised this novel numerous times. To be truthful, nine complete times.

Each time, I revised for a different component or a combination: structure, layout and format, POV, language, plot, exposition that told but didn’t show, scenes comprised of action, dialogue and use of the five senses, transitions, tightening and cutting. This didn’t happen overnight. It took years. I’m fortunate because I am tenacious, and my persistence yielded a final draft.

I convinced myself it was time to give up seeking representation, and focus on representing myself to small, independent publishers. I submitted to three of them in a listing of the first 101 best. Turner Publishing was the first I submitted to, and has to its credit fourteen NY Times best-selling authors, and is listed in the top tier fastest-growing small publishers. The acquiring editor at Turner said my novel was “sensational,” something this author dreamt of hearing for years, and I secured a three-book deal for my trilogy. Would I do it again? Probably not with what I know now. I certainly wouldn’t give away my audio, film or foreign translation rights for sure!

The year I received the acceptance from Turner, the Chinese horoscope was the zodiac sign the Year of the Horse—I felt strong and powerful, and knew good things were in store for me. Perhaps I was also in the right place at the right time, but I’d done my homework, researched, and knew this publisher was interested in historical fiction. I feel truly blessed.

—

Nina Romano earned a B.S. from Ithaca College, an M.A. from Adelphi University and a B.A. and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from FIU. She’s a world traveler and lover of history. She lived in Rome, Italy, for twenty years, and is fluent in Italian and Spanish. She has authored a short story collection, The Other Side of the Gates, and has published five poetry collections and two poetry chapbooks with independent publishers. She co-authored Writing in a Changing World. Romano has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize in Poetry.

Nina Romano earned a B.S. from Ithaca College, an M.A. from Adelphi University and a B.A. and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from FIU. She’s a world traveler and lover of history. She lived in Rome, Italy, for twenty years, and is fluent in Italian and Spanish. She has authored a short story collection, The Other Side of the Gates, and has published five poetry collections and two poetry chapbooks with independent publishers. She co-authored Writing in a Changing World. Romano has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize in Poetry.

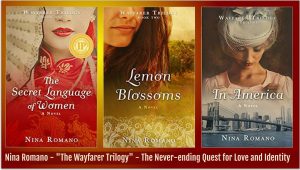

Nina Romano’s historical Wayfarer Trilogy has been published from Turner Publishing. The Secret Language of Women, Book #1, was a Foreword Reviews Book Award Finalist and Gold Medal winner of the Independent Publisher’s 2016 IPPY Book Award. Lemon Blossoms, Book # 2, was a Foreword Reviews Book Award Finalist, and In America, Book #3, was a finalist in Chanticleer Media’s Chatelaine Book Awards. She is currently working on a WIP set in Russia.

AMAZON: https://amzn.to/2MQZpNC

AMAZON Author Profile: https://amzn.to/2zVdmq9

GOODREADS: https://bit.ly/2PA0hHR

TWITTER: @ninsthewriter

FACEBOOK: https://bit.ly/2Eq6OUl

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing