I had Life Boredom and didn’t know it

By Elizabeth Gonzalez James

By Elizabeth Gonzalez James

I used to be a singer. From sixth grade on, I practiced scales and memorized entire musicals alone in my bedroom. I sang at competitions. My first job when I was sixteen was belting out operatic Happy Birthday serenades at Macaroni Grill. My senior year I was voted “Best Voice.” In those days I had no future plans other than somehow getting from my hometown of Corpus Christi, Texas to Broadway, and then somehow getting onstage. In high school I was sure all my dreams would come true. If I could only get to New York.

And then a weird thing happened. Around the beginning of my senior year of high school, when my other choir friends began flying to Chicago and New York and Boston to audition for different music schools, I didn’t join them. I didn’t visit campuses; I didn’t record a polished rendition of me singing Beethoven’s “Ich liebe dich.” I don’t think I even browsed music school websites. I couldn’t afford airplane tickets to any of those exotic locations—even the $80 application fees were a full weekend’s wages for me. But I was being stopped by something else, something perhaps even more obstructing than poverty.

By the fall of my senior year, I had decided not to go to music school, and that I would instead study Business Administration, choosing a practical major over a fanciful one. It’s a safer bet, I told my friends. I can always join a choir or something, get my singing in on the weekends. But I knew even that wasn’t the whole truth. Because when I said these things there was always at the back of my head an unspoken rejoinder, heard and absorbed by only me: Who was I kidding? I’d never get into music school anyway.

A couple of friends questioned the soundness of my decision, and made halfhearted attempts to talk me into at least auditioning, but that was it. If my parents and my choir teachers had opinions about my plans, they kept them inside. Life, it seemed, would not stage an intervention on my behalf. That winter I was accepted to the Retailing program at Syracuse University. By my own hand, with a checkmark in one box instead of another, my music career came to a sudden halt.

Except I didn’t stick with Retailing. I added a minor in Fashion Design but soon dropped it in favor of Asian History. Then I swapped Retailing for Art History. But before I graduated in 2004, I loaded up on American History courses because I was planning on applying to PhD programs in that area the next fall. (I took the GRE, but then never applied to any programs.)

After graduation I got a secretarial job at the university and tried to think about my future. I thought I might like to get into property development. No…fiber arts. I taught myself to crochet, but soon decided I should get a Masters in Accounting. I spoke to a faculty adviser who recommended an MBA instead, around which time I thought that perhaps it wasn’t too late to go back to school and study voice after all. I read a few books on music theory but decided law was a better path.

I prepared for the LSAT and taught myself basic logic, but switched course at the last moment and took the GMAT instead, finally enrolling in an MBA program in 2007. This brief and dizzying account of three years’ worth of career pursuits is not complete however, as I neglected to include the months I spent trying to get a job as a wedding planner, the semester I wrote a screenplay about vampire politicians, and the time I bought a bunch of leather and purse hardware because I had a business plan to upcycle t-shirts into handbags and sell them online. When I say this time was dizzying I mean it literally. Until I enrolled in graduate school I felt like I was stuck in the middle of some spinning plate act, racing from dish to dish, turning and turning my head, never sure where to stand or where to look.

And the ultimate irony was still to come: After finally arriving at a career path, after deciding in grad school that after graduation I wanted an entry-level job in corporate finance, I would find that all those jobs had vanished in the wake of the Great Recession. I would graduate from business school just a few months after the subprime mortgage crisis caused the collapse of Bear Sterns and Lehman Brothers. I would apply for between three and four hundred jobs, and I would get nothing. I would eventually give up and become a stay-at-home mother who started writing a novel in the evenings to preserve her sanity. And eventually, ten years later, that novel would find a publisher. But why did it have to be so hard? Why was choosing a career so, so difficult? What was wrong with me?

All these years later, I finally have an answer: I had life boredom.

Boredom is typically understood as a situational state—This movie is boring, This party is boring, etc.—but for some people, boredom follows wherever they go and colors every experience, suggesting that boredom may be a personality trait. And if this is true, it’s an especially pernicious one: Researchers have linked habitual boredom with drug use, criminal activity, and other self-destructive and risk-taking behaviors. And boredom differs greatly from depression. While a depressed person will generally blame themselves for their perceived shortcomings and lose hope of living a different life, the habitually bored person blames others for their situation, while remaining passively hopeful that someone will come along and rescue them.

Dr. Richard Bargdill of Virginia Commonwealth University has spent twenty years studying boredom and the way it manifests in people, and reading his work is like reading my own life story. In 2000 he published an investigation into the lives of six people and their experiences of life boredom, and their stories all follow the same trajectory: They had a goal, were thwarted from achieving this goal, and found themselves unfulfilled and unable to sustain enthusiasm for future projects.

Whereas participants’ pre-bored selves appeared to be unified toward their goals, they now were conflicted and divided… To some degree, the participants understood that they were turning away from their own-most selves, but felt compelled to work on these modified projects that they soon found their hearts were not in. This turning away from their own desires would become a repeated pattern of passivity and avoidance.

Had I been leaping from one career path to another to avoid contending with the fact that I’d torpedoed my own dreams because of low self-esteem? Was the endless pursuit of graduate programs and artistic fulfillment just my way of wishing to be rescued? Bargdill says ambivalence is a huge marker of life boredom, as well as finding oneself trapped in a cycle of attraction to a new and shiny project, only to abandon it at the first roadblock. Then the boredom spreads like ooze, swallowing up friends and hobbies until everything is boring, and everything is futile.

Futility is an important piece of this puzzle, too. Bargdill found that the subjects he interviewed were in a state of paralysis, frozen in place waiting to be rescued because they did not believe in their own ability to change their lives. This is one area where boredom and depression overlap, in a pervasive sense of emptiness, a lack of forward momentum, and an inability to see any meaningful shape in life. “Habitual Boredom is an encounter of nihilism,” Bargdill wrote in Toward a Theory of Habitual Boredom in 2014, “the bored person’s total lack of pre-ordained meaning in human existence.”

This reminds me of the Jose Luis Borges story, “The Immortal,” wherein a narrator finds immortal beings lying facedown in some shallow sand pits. When he asks them why they’re just lying there, they respond by saying that they’re basically bored, that they’ve done everything there is to do in life, that an immortal life has no shape because they will not die, and that the only logical thing for them to do then is lie facedown in the dirt. Oh Il-nam, the old man in Squid Game, complains of a similar predicament.

“Peoples’ identities are made up of who they have been, how they find themselves now, and what they intend to become,” Bargdill writes. Having a future identity in mind is important for growth because it gives you a destination. I want to be a person who can run a 5k, for instance, or I want to be a person who spends more time with my children. In order to become this future person, you have to use your experiences and skills to grow. But inside of life boredom, this process of becoming is blocked. On this Bargdill does not mince words. Life boredom coalesces into “a general sense of stagnation,” as he puts it. Recalling my own years of frustrated ambitions, it did often feel like lying facedown in the dirt.

In a sense I was eventually rescued from my predicament. After grad school, after a year of his own unemployment, my husband found a job that could support us, and I got pregnant. Without a job to leave once the baby came, I decided I would stay at home with my newborn, and I also decided that I would use my scant downtime to take a more serious stab at writing, something I’d flirted with on and off for years. I told myself that my time at home with my new baby was an opportunity. I could try writing for five years, five years of diapers and playdates and Thomas and Friends, as well as dozens of Writers Digest articles on character development and plotting, and many stolen moments alone with Toni Morrison or George Saunders.

If by the end of five years I didn’t have a published novel or any meaningful progress toward publication, I would quit and try something else. And I don’t know why writing stuck when so many of my other career pursuits failed, but I have to believe it had to do with the fact that my options were severely limited to things I could do for free, in small snatches of time, inside my tiny apartment while raising a baby. “Those participants who did [resolve their experience of boredom],” Bargdill writes, “typically returned to having an active sense of agency because someone else forced them to do so…This meant returning to active participation in their lives.” I’d found freedom through constriction, finally able to allow myself to pursue one goal with singular focus because I had scant other options.

I started writing and I liked it. I joined a Meetup for local writers and found that my work was actually pretty good. I could read about a technique in a book and then apply it to my novel and see the story improve in real time. I could start to analyze the novels I read, parsing sentences for subtext, tone, and theme. It was an incredible, alchemical time. And that’s not to say it was without setbacks. But I didn’t think of quitting. The stakes were somehow different this time. Perhaps because I had failed to follow through with so many projects, I felt especially driven to complete this, to see one thing all the way to the end. And besides, I could see my stories getting stronger, my thoughts more clearly expressed. I hate to quote my fellow Texan Ross Perot, but I think constantly about one thing he said: “Most people give up just when they’re about to achieve success… They give up at the last minute of the game one foot from a winning touchdown.” I couldn’t be certain how far away I was from the goal line, but I didn’t want to walk away when I could see something like success shimmering on the horizon.

I finished my first novel in 2015, exactly five years after I’d started writing. That same year I got a literary agent and went on submission. My book failed to find a publisher that year, but I still didn’t give up on it, and this summer it finally made its debut. The subject of my novel is a story that will sound familiar: An ambitious young woman loses her Wall Street job during the Great Recession, and finds herself in a tailspin of unemployment and self-loathing when she cannot figure out what she wants to do next. Fortunately for her and for me, after years of flailing and stumbling and spinning and failing, I’ve learned the antidote to a life of boredom: Find an achievable goal and go after it. It isn’t simple, but it’s the thing that’s finally given my life shape and meaning, and instilled in me the belief that I can impact my own trajectory. At almost forty I’m now in a place that was almost inconceivable to me twenty years ago, as shrouded as my own future was in smoke and shadows. But the next twenty years are not nearly as dim. From here I can see quite far.

—

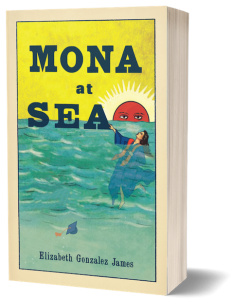

Before becoming a writer Elizabeth Gonzalez James was a waitress, a pollster, an Avon lady, and an opera singer. Her stories and essays have appeared in The Idaho Review, The Rumpus, StorySouth, PANK, and elsewhere, and have received numerous Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominations. She is the Interviews Editor at The Rumpus, as well as a regular contributor to Ploughshares Blog. Her first novel, MONA AT SEA, was a finalist in the 2019 SFWP Literary Awards judged by Carmen Maria Machado, and is available now from Santa Fe Writers Project. Originally from South Texas, Elizabeth now lives with her family in Massachusetts.

You can find her on Twitter and Instagram: @unefemmejames

Find out more about Elizabeth HERE

MONA AT SEA

Named Most Anticipated of 2021 by The Rumpus * Betches * Frolic * and The Millions!

Named Most Anticipated of 2021 by The Rumpus * Betches * Frolic * and The Millions!“A delightful debut…James is a writer to watch.” — ADAM JOHNSON, National Book Award winner and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Orphan Master’s Son

A darkly funny coming-of-age tale set against the backdrop of the Great Recession that takes the audience on a wild journey through a strange, uncertain modern America. For fans of Chloe Caldwell’s I’ll Tell You in Person and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

Mona Mireles is a quintessential overachiever: a former spelling bee champion and valedictorian of her college class, she has a sterling résumé and a wall of plaques and medals in her bedroom that stretches floor to ceiling.

She’s also broke, unemployed, back at home with her parents, and completely adrift in life and love.

Mona is seven months out of college and desperately trying to reassemble the pieces of her life after the Wall Street job she had waiting for her post-graduation dissolves in the wake of the Great Recession. When her reaction to losing her job goes viral and she is publicly branded the “Sad Millennial,” Mona begins a downward spiral into self-pity, bitterness, and late-night drunken binges on cat videos. Mona’s the sort who says exactly the right thing at absolutely the wrong moments, seeing the world through a cynic’s eyes.

Set in suburban Tucson amid the financial and social malaise of the early 2000s, 23-year-old Mona must not only find a job, but quickly learn to navigate the complexities of adult relationships within the black hole of her parents’ shattering marriage.

At her mother’s urging, Mona grudgingly joins a support group for job seekers, and slowly begins to see that all is not lost, and that perhaps losing the job on Wall Street was a blessing in disguise. She might even learn what it is she finds meaningful in life. The question is:

Will she be brave enough to go after it?

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips