Michelle Cruz: On Writing

If I’m honest, it’s Tom Clancy and John Grisham’s faults.

Although they weren’t exactly approved authors in my ultra-conservative upbringing, at least they weren’t forbidden. But there were few women, and—especially in Tom Clancy’s case—they were tangential to the plot, barely mentioned, and often more of a footnote. So in all the audacity of my teenage self, I decided to fix that, spurred on Beverly Cleary’s quote that if you don’t see the book on shelves you want, you should write it.

Although they weren’t exactly approved authors in my ultra-conservative upbringing, at least they weren’t forbidden. But there were few women, and—especially in Tom Clancy’s case—they were tangential to the plot, barely mentioned, and often more of a footnote. So in all the audacity of my teenage self, I decided to fix that, spurred on Beverly Cleary’s quote that if you don’t see the book on shelves you want, you should write it.

Given that I lived in a pre-Google/pre-Wikipedia age, in rural East Texas with no real connection at that time to the military, intelligence communities, or law, none of this fiction will ever see the light of day.

For the most part.

But in my early twenties, I dabbled with the draft of a novel that featured Reagan, the bored wife of a Dallas criminal defense attorney, Cade, drawn into a murder investigation after the widow of a law school classmate drops an envelope full of mystery into their laps. Even then, though, I knew it needed something, but I lacked the life experience and knowledge to know what.

Like so many women writers, I put my writing aside as I progressed in my twenties—first, for the sake of a career within the Air Force, and then for marriage and family. I left the military, but my days remained full, with two kids, an often deployed spouse, and graduate school. In my academic pursuits, I found an outlet for my writing in military/veteran advocacy; however, when I accepted a position as a district staffer for a congressional representative, I had to agree to give this up as a condition for employment.

It wasn’t until I had a health scare and then stood next to the casket of a state trooper even younger than myself that I realized if I died, the characters who still lived in my head died with me. Deciding that maybe it didn’t count as breaking my employment agreement if I wrote fiction under a pen name, I began quietly resuming my craft.

And I wrote some truly awful fiction in the search to find my adult voice.

At the first writers’ conference I attended, a man in the critique group I got placed in told me that I would never be published, because my writing was too soft and feminine to ever succeed in mystery, suspense, or thriller. I despaired the whole drive home from downtown Dallas, but my spouse’s response, “What, you’re going to quit and prove that guy right?” encouraged me to keep trying.

As lockdowns swept the nation in 2020, the Department of Defense was rocked with Vanessa Guillen’s murder. Although I was no longer employed by a member of Congress, I felt I had been out of the advocacy world too long to do anything more than proofread and suggest edits to the pieces written by my friends who were still in writing. But when I tried that can’t-help-wish-I-could-but-I-write-fluffy-fiction schtick, a friend/mentor pushed back, chiding me for minimizing my talents and pointing out the power of story. People, he reminded me, forget facts and numbers, but they’ll never forget a character. No one reaches for a policy paper when they’re stressed, but a novel can set the world on fire.

It was a September afternoon and I sat in my car in the elementary school pickup line, engine off, windows down, scanning over the bill introduced in Congress named for Vanessa Guillen. A woman’s voice whispered in my mind so clearly it was like she’d dropped into the passenger seat beside me, “Everyone has secrets. No matter how clever you are, there’s always the inevitable moment of carelessness. That’s where I come in.”

I pulled my phone out, opened my notes app, and started writing.

She was fiery hot, practically simmering with anger, but she somehow felt familiar. It wasn’t until the end of the first scene that she mentioned a Dallas criminal defense attorney named Cade, and I thought to ask her name. Reagan, she said, as if I ought to have known, and maybe I should have, even if this iteration was vastly different from the one I’d written what felt like a lifetime before. I churned through a first draft in just over sixty days, aided by how persistent her voice was in my head. And although one of my critique partners affectionately nicknamed her my little ball of rage, Reagan had plenty of reasons for her dogged pursuit of justice.

Reagan represents the 1.5% of American women that are military veterans. It’s a sisterhood forged in sweat, tears, and blood, a silent agreement to always have each other’s backs, and an acknowledgement of a community that often has to work twice as hard to get half as far, knowing that any individual mistake reflects on the collective. Although women veterans often struggle more quietly in transition to civilian life and are less obvious than their male counterparts, the indicators are there if someone knows where to look.

It wasn’t just the plight of her sisters-in-arms that had her so angry, but the injustices she saw around her and the secrets kept by those in power that had so much impact. Even knowing that not everyone would understand her or like her, I launched her out to the query trenches. When my dream agent requested a call only after eight weeks of querying, I laid my head on my desk and cried.

After a move this fall, I opened a large box and discovered all those manuscripts from my teenage years and early twenties. Many were handwritten, compiled into old binders I’d scrounged from abandoned school supplies. One was a stack of typewritten pages crammed loosely into a folder. I skimmed the opening paragraphs, prepared to consign it to the shred pile, until I saw the names of the characters in the first dialogue exchange between them.

No one may ever see that first ugly draft from nearly twenty years ago, now stowed safely in my desk drawer. That’s fine, because Reagan’s story—the one that was meant to be told, the one that I knew I wasn’t ready to tell all those years ago—will be out in the world in mid-March. Like her, love her, or hate her, I’m not sure she’ll care, so long as you’ll listen to the reasons why she’s doing her best to bring a little justice to her corner of the world.

Somehow, I think Tom Clancy, John Grisham and especially Beverly Cleary would approve.

—

Michelle Cruz is a seventh-generation native Texan who served as a commissioned officer in the United States Air Force and staffed a member of Congress. She resides with her family in the Texas Hill Country.

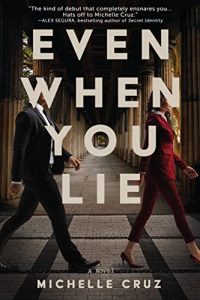

EVEN WHEN YOU LIE

Perfect for fans of Lisa Scottoline and Kimberly McCreight, Michelle Cruz’s debut novel will have readers furiously turning the pages as they plunge headlong into the seedy underbelly of glitzy and glamorous Dallas in this gripping Texas noir.

Perfect for fans of Lisa Scottoline and Kimberly McCreight, Michelle Cruz’s debut novel will have readers furiously turning the pages as they plunge headlong into the seedy underbelly of glitzy and glamorous Dallas in this gripping Texas noir.

Reagan Reyes hunts other people’s secrets. A former intelligence officer, she’s currently the in-house investigator for pricey criminal defense attorney, Cade McCarrick…and she’s his lover, despite the law firm’s rules forbidding romantic relationships between partners and staff. But their love—including their agreement never to lie to each other—is the only authenticity they have in a world of subterfuge and betrayal.

That agreement is pushed to its limits when a mysterious woman leaves an envelope for Cade and is soon discovered dead. While the envelope’s contents aren’t related to any of Cade’s current cases, Reagan uncovers a connection to a recent murder outside a Deep Ellum nightclub—and an even more ominous link to the dead woman.

The police don’t seem to care about either death, but they hit too close to home for Reagan to ignore. As she digs deeper into Dallas’s sordid underbelly, she’s completely on her own except for Cade—and there’s a killer bent on eliminating them both at any cost.

This pulse-pounding romantic thriller offers a fresh new take on big-city crime, from a dazzling and exciting new voice in the genre.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips