Minding the Gap: American Women Writers and World War I

Travel the roads from the scenes of battle; search the trains; wounded, frozen,

Travel the roads from the scenes of battle; search the trains; wounded, frozen,

starved thousands are dying in agonizing torture—not hundreds, but thousands.

—Nellie Bly, “Hospital in Budapest Is Arena of Horror,” Washington Herald, 20 Jan 1915

As famed reporter Nellie Bly makes clear, women witnessed and wrote about the horrors of World War I, but the war narratives that are remembered are predominantly male (think Erich Marie Remarque, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos).

If any activities of women are mentioned, they tend to be those of the most prominent (think Edith Wharton). Since the commemoration of World War I’s centenary began in August 2014, discussion of the war has received increased attention, including women’s participation in it (such as a new exhibition by the United Kingdom’s Imperial War Museum that features art by women in the war).

But what is disquieting is that few of these treatments deal with the varied roles of the nearly 100,000 American women in the war (a figure from the Overseas Women’s Service League) nor do they provide the women’s own perspectives.

As seen with Bly (whose World War I reporting appeared neither in her New York Times nor Washington Post obituary), this situation results in overlooked, minimized, or forgotten contributions and sacrifices of the U.S. women in the war.

Author and World War I nurse Vera Brittain asked in her autobiography Testament of Youth, “Didn’t women have their war as well?” Asking “didn’t American women have their war as well?,” I compiled In Their Own Words: American Women in World War I to highlight first-person accounts by U.S. women in the war.

These include bestselling novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart, who covered the war for the Saturday Evening Post and held professional nursing credentials, and Grace Gallatin Thompson Seton, a travel writer who—on behalf of New York Women’s City Club—headed the Woman’s Motor Unit of Le Bien Etre du Blesse that transported food to diet kitchens at French aid stations (her daughter was author Anya Seton).

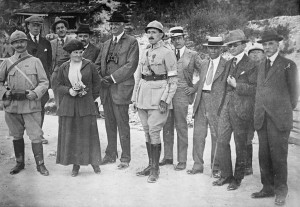

National Geographic’s Harriet Chalmers Adams with journalist Charles Edward Russell (third from right) and others in Rheims, France, ca. 1916. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Among the war correspondents represented are Bly; Harriet Chalmers Adams of National Geographic; Peggy Hull of the El Paso Morning Times; and Alice Rohe of United Press, the first female bureau chief of a U.S. press service. Also featured are suffrage playwright Elizabeth Robins, who worked in a London hospital during the war, and writer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, who was in Japan at the time of that country’s declaration of war on Germany and later worked in the paymaster general’s office in Washington, DC.

“What on Earth Is Mother Doing Here?”

Despite attempts by Saturday Evening Post editor George Lorimer to dissuade Rinehart from an assignment that meant exposure to sub-infested waters and other dangers, she headed to Europe in early January 1915. She interviewed the king and queen of Belgium as well as toured hospitals (resulting in the book Kings, Queens, and Pawns).

Once home, Rinehart visited army posts and naval stations in preparation for future articles she intended to write and reported her findings to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. “[C]ommanding officers had consulted my ignorant self about the construction of trenches,” she stated deprecatingly and then proceeded to point out deficiencies in trench construction that she had seen at Fort McPherson and were based on trenches she had seen in Europe.

She did not remain stateside. According to an NPR interview with Rinehart’s great-grandson, Stanley Rinehart Jr.—in France with the AEF—learned of his mother’s presence in the country in 1917 and sent the following telegram to his father: “What on earth is Mother doing here?”

Chalmers Adams, an explorer listed as the first woman permitted to visit French front-line trenches, wrote of being caught in an air raid: “…[W]e all bolted for the nearest house with the biggest Lorraine cross. . . .We had barely reached the cellar steps when the first crash came.

I have never heard anything as ominous as the sound of those Titanic shells, each crushing out homes and human beings.” Rohe covered the war in Italy, writing of a treatment facility for servicemen traumatized by war, “It is the garden of hope, the oasis where the human will is supreme, the haven where wreckage of war, men cast into the waste of life, are saved from the refuse.”

The women themselves did not emerge unscathed. Because Hull obtained privileged access to an AEF training camp that stemmed from a prior acquaintance with General John J. Pershing, male reporters retaliated and had her recalled to Paris, thereby limiting what she could cover from that point forward.

Rohe eventually left journalism because she could not earn wages equal to male correspondents. Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, who wrote for periodicals such as Century, McClure’s, and the New Republic, was seriously injured when a member of her party touring a battlefield picked up a live grenade.

Poet Gladys Cornwell, after experiencing constant bombardment as a canteen worker in France, committed suicide by jumping from the S. S. La Lorraine on her way home to the United States. Some 350 other American women in military roles died during their war service—four under combat conditions, and many others due to complications from influenza.

As the centenary of the U.S. entry into World War I approaches in 2017, it is important to acknowledge the full picture of the war—one that incorporates the many roles and voices of American women.

—

Elizabeth Foxwell is managing editor of Clues: A Journal of Detection (the only U.S. scholarly journal on mystery and detective fiction) and editor of the series McFarland Companions to Mystery Fiction. In conjunction with her anthology on U.S. women in World War I, she has created the blog American Women in World War I.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post