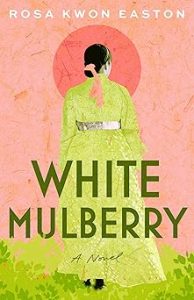

My Immigration Story and the Role it Played in Writing My Historical Debut Novel White Mulberry

by Rosa Kwon Easton

White Mulberry is inspired by the life of my Korean grandmother, a young woman coming of age in 1930s Japan-occupied Korea. The story follows the journey of Miyoung, an eleven-year-old girl who has dreams too big for her poor, farming village outside Pyongyang – to become a teacher and avoid an arranged marriage. When she’s offered the chance to live with her older sister in Japan and continue her education, she’s elated, but soon realizes she must pass as Japanese to survive in a society rife with anti-Korean sentiment.

White Mulberry is a rich, deeply researched novel, about a woman torn between two worlds, and her quest to reclaim her true self. It’s a story of resilience, love, and the power of identity. It is also an immigrant story. While White Mulberry is set in a different place and time, the theme of being an outsider and searching for belonging is one that resonates with many immigrants, including me.

My family immigrated to Los Angeles from Seoul, South Korea in 1971, when I was seven years old. My parents brought me and my two younger brothers here for better economic and educational opportunities. In essence, my family moved for the same reason Miyoung in my novel did—for a better future. Sadly for Miyoung at the time, she moved because girls in Korea couldn’t go to school past primary school. Education, and the pursuit of it, is also an important aspect of my novel, as well as my own family’s immigrant dreams.

When we immigrated to LA, my younger brothers and I didn’t speak any English and had very little knowledge of American society, culture, or customs. We stood out, so we changed our old Korean behaviors to resemble those of the dominant American culture through a process of assimilation. We acquired “American” names, watched popular TV shows like The Partidge Family, and wore jeans and tennis shoes. We imitated everyone else because that was how we were going to adapt and survive.

For me I copied whole novels into my notebooks so I could learn English and the American way of life. I checked out books from our local library by authors such as Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, and Laura Ingalls Wilder. I never saw characters that looked like me in those books, so I began to emulate the characters I read about to become more American.

That’s what Miyoung did in my novel, too. She passed as Japanese in a society that didn’t accept her. For Miyoung, she looked Japanese and spoke fluent Japanese, so it was easy to blend in. It was a decision she had to make to survive. But it caused a lot of pain, to repress an essential part of herself.

Assimilating is what my brothers and I also did to survive. We slowly shed our old Korean selves in favor of the new American ones. We denied a part of who we were to fit into mainstream society, because that was what we thought society, and our family, expected. We thought we had to identify with the dominant white American culture in order to succeed.

Meanwhile our parents had difficulties too. My father, a former banker with an MBA in Korea, used to cry at the dinner table at night after coming home from cleaning bathrooms as a janitor. My mother, also an educated woman in Korea, stood up for eight hours straight on an assembly line during her graveyard shift, and then had to take care of three small children. They couldn’t afford to pay a babysitter, so my mother had to call her mother to come from Korea to help. My father eventually became an accountant and built a successful accounting practice with my mom as the general manager, but it took years, and we became latchkey kids.

In White Mulberry, Miyoung worked as a server in a Japanese restaurant until one of her male co-workers, someone she liked, discovered she was Korean and got her fired. Miyoung then passed as a Japanese maid and kept to herself to avoid getting hurt. She eventually married a Korean activist, but became a widow with an infant son when she was just twenty. She studied to become a nurse and midwife to support her family, but had to continue to pass as Japanese to acquire and keep her jobs.

While Miyoung was able to “pass” as Japanese to blend in, I couldn’t do the same in America even if I wanted to because of my race. I longed to be like everyone else, not someone who was different and an outsider in society. I rejected my Korean heritage and was embarassed about my slanted eyes and straight brown hair. My heart sank at hearing my parents’ broken English at parent/teacher conferences, when the teachers would have to speak ever so slowly and I would have to translate. I made fun of myself alongside my classmates when they teased me. “Hey, Chink! Go home!” It sounds cliché, but I went along to get along.

I threw myself into my studies because I didn’t want to be judged by my looks. I was voted Most Likely to Succeed in high school, went to a good college, became a lawyer, married, and had two wonderful children. On the outside, I met all the external requirements for success.

But inside I often felt invisible and powerless. I was conflicted about who I was, but couldn’t talk about it with anyone. I was ashamed of myself, my family, and my birthplace. That shame stayed with me even as I grew into adulthood. I only started becoming curious about my Korean identity in college after a summer of learning Korean in Korea. I began to reconcile my American self with my Korean past. I began to lean into my heritage, and see a new, more whole version of myself.

For the first time, I became interested in my own family’s history. I spent my junior year abroad in Kyoto, where I discovered that I had Korean Japanese relatives who were third or fourth generation Koreans, yet they were still treated differently because of their race. I discovered my grandmother’s old nursing and midwife certificates written in Japanese. I wondered why she was a Korean woman living in Japan, and wanted to know more about her. I wanted to re-embrace my heritage and my Korean identity. I didn’t know it, but the seeds of my novel were planted then.

In novel writing, there must be conflict to move the story forward. In White Mulberry, the central conflict is the question of identity and who Miyoung is: Is she Korean? Is she Japanese? My conflict growing up was the same: was I Korean? Was I American? Was I “passing” too, and not embracing my complete self like Miyoung was? I didn’t have to look far in order to write scenes for my novel: they came straight from my own childhood and experience.

I internalized a lot of pain growing up, which I began to unravel as I wrote. To me, writing was therapy, to be able to heal through writing about my grandmother’s experience, discovering my own story, and perhaps coming up with a different outcome. This is the ending to my story—publishing my novel—and sharing my grandmother’s incredible immigrant story, and in turn my own, with the world. By doing so, I hope to empower all of us to explore, share, and celebrate our authentic selves. I hope we will see ourselves and others differently, and in some small way, change the way we think.

—

Rosa Kwon Easton was born in Seoul, Korea, and grew up with her extended family in Los Angeles. Easton holds a bachelor’s degree in government from Smith College, a master’s in international and public affairs from Columbia University, and a JD from Boston College Law School. She is a lawyer and an elected trustee of the Palos Verdes Library District. She has two adult children and lives with her husband and Maltipoo in sunny Southern California.

WHITE MULBERRY

“A beautiful and deeply researched novel…If you loved Pachinko, you’ll love White Mulberry.” —Lisa See, New York Times bestselling author of The Island of Sea Women

“A beautiful and deeply researched novel…If you loved Pachinko, you’ll love White Mulberry.” —Lisa See, New York Times bestselling author of The Island of Sea Women

Inspired by the life of Easton’s grandmother, White Mulberry is a rich, deeply moving portrait of a young Korean woman in 1930s Japan who is torn between two worlds and must reclaim her true identity to provide a future for her family.

1928, Japan-occupied Korea. Eleven-year-old Miyoung has dreams too big for her tiny farming village near Pyongyang: to become a teacher, to avoid an arranged marriage, to write her own future. When she is offered the chance to live with her older sister in Japan and continue her education, she is elated, even though it means leaving her sick mother—and her very name—behind.

In Kyoto, anti-Korean sentiment is rising every day, and Miyoung quickly realizes she must pass as Japanese if she expects to survive. Her Japanese name, Miyoko, helps her find a new calling as a nurse, but as the years go by, she fears that her true self is slipping away. She seeks solace in a Korean church group and, within it, finds something she never expected: a romance with an activist that reignites her sense of purpose and gives her a cherished son.

As war looms on a new front and Miyoung feels the constraints of her adopted home tighten, she is faced with a choice that will change her life—and the lives of those she loves—forever.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing