My Top 7 Memoir-Writing Lessons

Writing memoir is a tricky thing. Memoirists, like me, find real-life images to describe weaving life events into the story of our lives. For the seamstress, it’s like fashioning fabric; for the potter, molding a lump of clay into something recognizable; for the builder, it’s construction from the foundation.

As a former Mennonite, my history is bound up in my European heritage. My forebears, most of them farmers, emigrated from Switzerland to escape religious persecution and claim land in Pennsylvania offered by William Penn during the early 1700s. When I visited the Longenecker dairy farm in Langnau, Switzerland, in some ways it felt like coming home.

Paging through a photo album of my trip to Switzerland, I’ve discovered that the contours of the Swiss Alps with its “W” shape fits the plot and theme my story of the first twenty-four years of my life in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The ups and downs of my path toward transformation mimic the jagged angles of alpine topography.

Finding the right shape for telling our stories is a critical step in the memoir writing process. Writers call it the narrative arc. Such an arc is not set in stone: It’s flexible and can change as the story unfolds.

1. First, I created a timeline of vivid memories in my life. This is how I hoped to arrive at my turning points, moments of significant change. As I drew, I thought in terms of chronology. What is my first memory? What stands out in elementary school? What family event pops up? Who looms large as a mentor? Answers to these questions became turning points.

2. Then I thought about scenes. On coloured sticky notes, I randomly wrote phrases that came to mind. For example: The phrase “Daddy yodeling” could turn into a scene about my sisters and me taking turns singing with Daddy at the piano, relating to the impact of music upon my formative years.

3. Next, I gathered random scenes into a sensible order, based on theme. For some writers, it could be about recovering from a challenging situation like an illness or abuse, or perhaps the struggle of becoming a chef.

3. Next, I gathered random scenes into a sensible order, based on theme. For some writers, it could be about recovering from a challenging situation like an illness or abuse, or perhaps the struggle of becoming a chef.

I chose scenes based on how well they related to my theme, the message of my memoir. My own theme can be stated like a question: How can a girl from a sheltered and restrictive Mennonite culture find her place in an emerging new life?

A memoir is not an autobiography. I couldn’t include every detail of my entire life. I selected only those scenes that related to my theme of how I searched for ways to express my true self as a young woman.

4. Sometimes I felt stuck. Fatigue set in during a long climb. Air became more rare as I moved into a higher altitude, “alp-titude” in Swiss terms. I took breaks – hours in a day, sometimes weeks or months. During the nearly six years time it took to write my memoir, three family members died. Thus, there were time-outs to settle their estates and clear out their houses. While these were hardly vacations, I returned to my manuscript with fresh eyes.

5. I printed out drafts. As I progressed, I printed out drafts from my laptop. Although corresponding manuscripts were placed in labeled folders on my computer desktop, I found it helpful to print out the story, touch the pages, and make marginal notes in colored ink. It felt book-like, more real.

6. I tried to overlook messiness in my workspace. Generally, I’m a “neatnik,” but worries about order, except in my writing, distracted from my creative process. If you are a “creative messy,” no need to worry about this point.

7. From the beginning, I connected with published authors I admire. Coming from an academic background, I had to learn the basics of storytelling. Taking courses on craft helped, but so did soliciting authors to read my memoir drafts. Some I met on a retreat; others through my blog.

Writers tend to get tunnel vision. That’s why we need other readers, beta readers, who scrutinize their manuscripts.

Beta Readers, numbering in the double digits, read my drafts with a spyglass. They used microscopes, telescopes, and periscopes. Some even used prisms to enable me to see the draft from many angles. Most accepted a digital copy, using Track Changes, a feature of Microsoft WORD, for their suggestions. I mailed a hard copy to two authors who wrote marginal suggestions.

My first reader asked, “What is your story about?” (Not a good sign!) I sighed because I thought my story theme was obvious. Apparently not, so back to the drawing board I went.

As I waited for their constructive analysis, I read and reviewed their books, both memoir and novels. It’s good to remember that in the writing community, reciprocity is a good thing.

***

What followed: Multiple revisions, searching for a title, engaging developmental editors and a copyeditor, securing a design company for layout and publishing, and figuring out the how-to of book promotion.

Some final thoughts:

Writing memoir is hard, but so rewarding. As memoirist Jerry Waxler puts it, “Your effort to turn your memories into a coherent whole is both a literary endeavor (you’re writing a book), and a psychological one (you’re reconstructing and repairing part of your own psyche).

Sometimes at my desk I had been so into a scene that when I looked away from the manuscript, I was surprised to find I was at home in my writing studio and not trying on hats in my Grandma Longenecker’s bedroom long ago. If the scene was difficult to re-live, I was there too. With Mary Karr, I believe that zipping oneself into the skin of one’s former self is a key to memoir-writing success.

Memoir as Legacy

As Laurence Overmire, states in Digging for Ancestral Gold, “ If you can make your ancestors real for yourself, learn their stories and who they were, your life – and death – will take on added meaning. You will see yourself in the Big Picture that includes all human life that has come and gone on the planet.” I couldn’t agree more.

LINKS:

Book:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07XL5FPW6

Blog: https://marianbeaman.com

https://marianbeaman.com/2018/09/26/what-editing-looks-like-memoir-update/

https://themennonite.org/issue/september-food-faith/

“Making Love Edible: Lessons from Fannie Martin Longenecker”

https://facebook.com/marianbeaman

https://twitter.com/martabeaman

https://instagram.com/marianbeaman

—

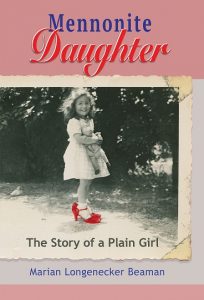

MENNONITE DAUGHTER: THE STORY OF A PLAIN GIRL, Marian Longenecker Beaman

Mennonite Daughter: The Story of a Plain Girl, Marian Longenecker Beaman

What if the Mennonite life young Marian Longenecker chafed against offered the chance for a new beginning? What if her two Lancaster County homes with three generations of family were the perfect launch pad for a brighter future? Readers who long for a simpler life can smell the aroma of saffron-infused potpie in Grandma’s kitchen, hear the strains of four-part a capella music at church, and see the miracle of a divine healing.

Follow the author in pigtails as a child and later with a prayer cap, bucking a heavy-handed father and challenging church rules. Feel the terror of being locked behind a cellar door. Observe the horror of feeling defenseless before a conclave of bishops, an event propelling her into a different world.

Fans of coming-of-age stories will delight in one woman’s surprising path toward self-discovery, a self that lets her revel in shiny red shoes.

In Mennonite Daughter–Story of a Plain Girl, Marian Beaman invites you into a world gone by with a loving tribute to her Mennonite family. We learn how we may cling to our roots while needing to find our own path, and how our growth can include respect for the past while creating new family traditions. You will be charmed by her depiction of a simple, plain life in a Mennonite community in the fifties, and her gentle shift into modern times.

–Linda Joy Myers, Founder of the National Association of Memoir Writers, author of Don’t Call Me Mother and Song of the Plains

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: How To and Tips

So interesting, thank you. I found the Quaker tradition of journalling was helpful to get me started into serious writing. (Writing is a thing I’ve always done, but it took me a while to take it seriously.)

All the best,

Fran Macilvey