My Top Tips For Writing Historical Novels

By Mary Chamberlain

By Mary Chamberlain

As a historical novelist – and also a historian – I’m often asked for suggestions or advice so here are my top tips for writing historical novels…

Tailor your research.

What sort of a historical novel are you writing? Are you, like Hilary Mantel, using fiction to enter into historical debate, as she did with her remarkable Wolf Hall trilogy? In which case, you will need to get to grips with a considerable amount of serious research in libraries and archives on political intercourse and discourse, and the life and manners of Tudor England.

Or are you writing a novel set in, say Regency England, because you love the costumes and houses of the times, with a romance in mind? In which case, your research will focus less on, say, the political context or historical debate, and more on domestic and cultural history.

Or, perhaps, you wish to cast a spotlight on a painful past that has been too often ignored, such as Marlon James The Book of Night Women, or use history to unveil a fresh understanding of contemporary issues, such as Barbara Kingsolver’s Lacuna? In which case… well, you get my meaning. Asking how much research is necessary is like asking how long is a piece of string.

You do enough research to immerse yourself in the period of your novel and its subject matter.

Then stop.

Put it aside.

Start writing.

Wear your research lightly, integrate it casually

The depth of research depends on your purpose. BUT remember – you are writing fiction not history, this is a work of the imagination, not scholarship. Do the research but don’t be intimidated by it, don’t be hemmed in by it, don’t feel you need to get it right.’

It’s the authentic feel that you need. Don’t show off your research, use it sparingly, but pointedly. Immerse yourself in your story, imagine you are there in classical Rome, or medieval Japan, or war time Italy and select only the small, telling details that will allow you to convey authenticity.

We live through our own contemporary times and take for granted so much of what surrounds us. It was the same for those living in the past. They wouldn’t labour what they see, it would just be there, taken for granted and that is what you need to convey. Less is always more: wear your research lightly, integrate it casually. What your research has given you is a squirrel’s hoard for the winter; but you eat it up, one grain at a time.

More than that: you need to digest it, and then re-imagine it…

Use your (historical) imagination

Choose – invent – a good story, and remember that historical fiction can also play with other genres – it can also be a thriller, a whodunit, a ghost story. It can be a romance, or a retelling of an old story or myth, or highlight a moment in history.

If you are using the biography of someone who lived as the theme of your novel then, obviously, you will be constrained by his or her life. But you can still invent the persona, the character, the language. You can invent the emotions, the scenes, the conversations as if you had invented the story from scratch.

You must, in other words, imagine your story as if it was any other kind of fiction.

Use your common sense(s)

You’ve invented a story – now you need to turn the story into something that lives, to people it with characters who have drives and desires, flaws and foibles. Use all the senses to convey what your character(s) see, hear, taste, smell, touch. The senses are a great way – and an economical way – to relate to, and relate, the past, whether it’s classical Troy, Shakespeare’s Stratford, 1950s West Coast America. The senses enable an author to get right inside the head and body and to experience the world as your characters experience it.

But – beware of the anachronisms. Think about the language that you use to convey inner thoughts, mentalities, emotions. Think about the verbs you use to convey action and emotion, the words to convey atmosphere to evoke their historical and social/geographic setting. Get inside your character’s head – but always remember where they are in time and place.

Human sensibilities are different between cultures, and over time. Professional historians use the word ‘mentalities’ to talk about the ways thoughts and beliefs were contained within an historical period, and that’s a concept useful to historical fiction writers. So be careful not to inject modern sensibilities into your historical fiction.

The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there. L.P.Hartley The Go Between.

Finally a few words on plotting and all that jazz

Remember: the story is what you tell, the voice is how you tell it (narrative style), the plot is the route it must follow, the point of view is the perspective you take – singular, multiple or omnipresent.

Some writers map out the plot in detail; others have a vague direction in their head. Choose what is most comfortable for you, and then play with the voice and point of view. Think of the rhythm of your prose, the rhythms of your dialogues, think what means best suits the story you are telling.

Then there’s nothing for it but to plunge in…

—

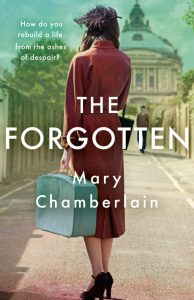

Mary Chamberlain is a novelist and a historian. Her debut, The Dressmaker of Dachau (UK) The Dressmaker’s War (USA) sold to 19 countries and was an international best seller. Her second novel, The Hidden, set in the Channel Islands under the German occupation was made a Sunday Times ‘must-read’ choice in 2019. Her new novel, The Forgotten, will be published in September 2021.

As a historian, Mary Chamberlain was one of the pioneers of oral history and has written widely on women’s history and Caribbean history. Her first book, Fenwomen: a portrait of women in an English village, was the first book published by Virago Press, and was the inspiration behind Caryl Churchill’s award-winning play, Fen.

Twitter @marychamberla12

Facebook @marychamberlainauthor

THE FORGOTTEN

The latest book from bestselling novelist Mary Chamberlain

The latest book from bestselling novelist Mary Chamberlain

How do you rebuild a life from the ashes of despair?

London 1958. Twenty-six-year-old Betty Fisher is one of the first to join the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and attend its inaugural meeting, where she meets John Harris. Posted to Berlin towards the end of the war, John has been left traumatised by his experiences in Germany. And, as his initial admiration for Betty shifts into an overwhelming need to protect her, he is plagued by flashbacks and fantasies. John’s increasing fragility brings to the surface Betty’s own memories. And soon her past, too, begins to unravel…

Preorder HERE

Category: How To and Tips

Great tips! Thank you for sharing. I especially like your point about how we should not “inject” our modern way of thinking into the past. Great quote about how the past is a “foreign country”!

Thank you very much – I’m delighted you found it helpful!