On Writing Memento Mori by Eunice Hong

Memento Mori revolves around different interpretations of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, as told by a Korean woman to her younger brother. In its simplest and most well-known form, the story goes something like this:

Memento Mori revolves around different interpretations of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, as told by a Korean woman to her younger brother. In its simplest and most well-known form, the story goes something like this:

On her wedding day, Eurydice dies of a snakebite. Grief-stricken Orpheus, newly wedded and widowed, descends to the underworld to bring her back. A musician of divine skill, he plays the lyre so beautifully that Persephone and Hades, the gods of the underworld, agree to reunite him with his wife. They impose only one condition: Orpheus must walk ahead of Eurydice without looking back at her until they both reach the surface. Simple enough. Just before he takes the final step, however, he looks back, and Eurydice vanishes forever—if indeed she was ever there at all.

As a child, I was haunted by that last step. I obsessed over the question that invariably follows: Why does he look back? As I grew older, though, my heartache for his plight hardened into disdain. Only a reckless, selfish idiot would squander that rare gift of a second chance. Does he have no self-control? Is he stupid?

It never crossed my mind to ask whether Eurydice wanted to come back.

But then my beloved grandmother, the cradle of my childhood, began to slip away from me. What started as a feeling of déjà vu devolved into wholesale repeated conversations intermingled with strange tales that I wasn’t always sure were true. I began to write down every story she told me, from her childhood in Japan-occupied Korea to the flowering trees she saw that morning in the park with her friends.

Soon thereafter, we learned that Alzheimer’s disease was starting to tangle her memories. Five years, the doctor told us. Ten, if she’s lucky.

My parents devoted their lives to her care. They wanted to make sure they gave her the chance to be lucky. But even as she far outlived her doctor’s expectations, she became a diminished shadow of herself. She grew too tired to walk in her garden and required a wheelchair. She set her books aside and glued her eyes to the television until her head became too heavy for her neck. When she forgot the words to her favorite hymns, I played the melodies on my cello, but she barely acknowledged my presence. When she looked at me, she did not know me.

She stopped speaking. She stopped eating. The doctor told us she had forgotten how to swallow and instructed my mother to give her an IV of essential nutrients. Though the IV kept my grandmother’s heart beating, her weakening limbs kept her bedbound. Each time her breathing faltered, I clutched her hands and wept for her to please stay with me.

Once in a while, she came alive again. We could never predict the days that she would suddenly eat well and laugh with us and remember our names. But behind those precious flashes of lucidity, I could sense her wondering what she was still doing here. A devout Christian her whole life, she had often told me that she was not afraid of God calling her to heaven. She would welcome the blessing of God’s peace, she said, and she looked forward to reuniting with her husband, the grandfather who died before I was born.

But I did not share her unshakeable faith. I knew only that I was terrified of death and that I loved my grandmother beyond reason. I clung to her life because she would not. I was incapable of considering that perhaps she did not want to come back—that she was content with the life she had lived, and she was ready to move on from a body worn away by time and disease.

The last morning of her life, she again refused to eat. We tried everything to cajole her, but she would not swallow. My mother said we could try again in a little bit and tucked her back into bed without the IV. As my grandmother curled up onto her arm, she gave me a bright, loving, uncomplicated smile before drifting off to sleep.

An hour later, she died.

I expected to wallow for months, maybe years. Instead, I forgot. I wasn’t delusional; I knew she was dead. But unless someone directly asked me about her, my brain papered over her passing as if it had never happened. It was only a year later, in preparation for her memorial service, that the reality of her death started to sink in as I tried to capture in words the life I had been so desperate to preserve at the cost of her happiness. As I looked back, I was finally forced to acknowledge that my grandmother no longer existed except in the stories and memories she left me. And though I mourned her absence, I was also profoundly grateful that she no longer suffered.

Perhaps, then, Orpheus does not look back because he is reckless or selfish or stupid, but because he knows how the story must end. He cannot help trying to regain what he has lost—who of us can?—but he also recognizes that the very nature of looking back means accepting what is and should remain in the past. Perhaps, when Orpheus looks back at Eurydice, he performs his last and greatest act of love—he lets her go.

—

Eunice Hong is the director of the Leadership Initiative and a lecturer in law at Columbia Law School. She was previously a litigation associate at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP and a law clerk to the Honorable Richard M. Berman in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. Eunice received her J.D. from Columbia Law School after graduating from Phillips Academy Andover and Brown University. She resides in New York, New York. Her author website is www.eunicehong.com, and she can be found on Instagram (@eunicejhhong) and Twitter (@eunicehong). MEMENTO MORI is her first novel.

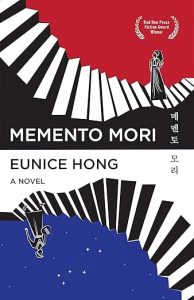

MEMENTO MORI

Don’t look back.

Don’t look back.

Did Eurydice want to return from the underworld? Did anybody ask?

In this brilliant portrait of rage and resilience, a Korean woman tries to connect with her younger brother and grapple with family tragedy through bedtime stories that weave together Greek mythology, neuroscience, and tales from their grandmother’s slipping memory.

Recasting the myths of Eurydice, Orpheus, Persephone, and Hades through the lens of a Korean American family, Eunice Hong’s debut novel offers a moving and darkly funny exploration of grief, love, and the inescapability of death.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing