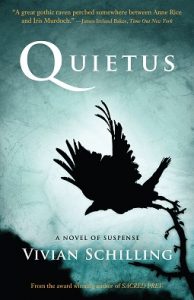

QUIETUS A Spirit of Thought

On a Boston winter’s day long past, I began my journey into the tactile world of Quietus. Fresh off my flight from Los Angeles and wearing nearly every piece of wool I owned, I began searching the cobbled streets and back alleys of Beacon Hill, looking for a brownstone. I was there to map and piece together the physical lives of my characters and to take my plot to the next level. I wanted a residence at the top of a hill, one of considerable size that would provide a marker for the home of socialite Dora Greyson. My protagonist, Kylie O’Rourke, would spend much of her time there working on the mansion’s renovations.

On a Boston winter’s day long past, I began my journey into the tactile world of Quietus. Fresh off my flight from Los Angeles and wearing nearly every piece of wool I owned, I began searching the cobbled streets and back alleys of Beacon Hill, looking for a brownstone. I was there to map and piece together the physical lives of my characters and to take my plot to the next level. I wanted a residence at the top of a hill, one of considerable size that would provide a marker for the home of socialite Dora Greyson. My protagonist, Kylie O’Rourke, would spend much of her time there working on the mansion’s renovations.

From the beginning, there was never any doubt that Quietus was to take place in Boston, in the New England city with its vibrant youth and rich history, its sizable Catholic population and Irish diaspora. A city of art and intellect, of the working man and pride. With its shadowy streets, river walks and far-reaching subway, it was a place a character could get lost in on her journey inward.

The seed for Quietus was borne out of a dark night in my eighteenth year when the car I was traveling in slammed into a tree at an estimated sixty-five miles an hour. I was an unbuckled passenger in the front seat, yet I inexplicably survived the impact with only minor injuries. Four years later, I lost both of my parents unexpectedly. As a young woman, I found myself face to face with mortality, struggling to comprehend its seemingly ruthless and random nature. Though it would be years before I would write Quietus, my grief led me on an existential journey into the vast subject of death, into the world’s philosophical, spiritual and cultural views surrounding life’s greatest mystery—what happens after the body’s last breath.

Quietus is titled after the moment of death. It is about body and spirit and the tenuous thread of breath that connects the two. Though full of hope, it treads into the darkened territories of the human spirit, into dreams and memory, and the unreliable convictions of the past. It toes the liminal space between life and death as my protagonist searches for answers to her own harrowing brush with mortality after her plane goes down in the White Mountains.

Thirty-four-year-old Kylie O’Rourke emerged as my protagonist for a reason, but the particulars of her circumstances continued to elude me, my instincts telling me that an undercurrent had stretched through her life long before the fateful crash. I felt strongly she was a daughter of Boston and knew I could find the answers there.

Konstanin Stanislavski once said, “The truth in art is in the truth of your circumstances.” A well-prepared actor must ground himself in his situation by looking to the moment, to the earth at his feet. Only then can he begin to act and through the doing find his truth.

Like an actor, a novelist must step into the perspective of each of her characters and ground them in their circumstances to build honest worlds around them. Without a place to act, a character remains a disembodied idea without true intention or will. I knew once Kylie and the rest of my characters were at home in their physical space, my understanding of them would increase tenfold. At that point they would begin to act and help guide the story where it needed to go.

On the second day of that first wintry trip to Boston, I am drawn to Swampscott to learn more about Kylie’s father, Sean McCallum. I know little more than that he is a first generation Irish American whose wife had died years earlier and that he is a lobsterman by trade.

With the fishermen’s cottages behind me, I stand at the iced edge of Nahant Bay, uncertain where to turn next, when I am drawn to a narrow pier that extends fifty-feet out over the water. Invigorated by the sting of the cold, I grasp the rope railing and edge out onto the slatted walkway. As I take a look down into the ice-slushed water, the pier sways and my heart bolts. In the rush of adrenaline, a character I had not expected materializes before me. It is Dillon O’Rourke, the brother-in-law of Kylie, a young Harvard graduate and an accomplished cardiologist. At once, I know why he is there and the pit in my gut becomes a pit in his own, only his is of a deep sadness. As I feel the sting of the frigid air reach the depths of his heart, a critical subplot I had not foreseen expands before me, edging the door wider into Kylie’s world.

In the spring I revisit Nahant Bay, this time for a trip out on a boat so that I can better understand Sean McCallum’s trade. It is at the day’s end at the shoreline when I take in the salt air and reach for the lobster trap that the gentle giant appears before me. I see his sun-weathered face with blue eyes as clear as the sea at his boots, his hands large and weathered, scarred from hooks and hammers. I catch an errant scent of rye-whiskey and instantly know the pain and worry he has for his daughter. Imagining and staring into this moment, I see something of my own father, a working man who had a kind spirit and a body that had grown too tired too young.

After standing close enough to Sean McCallum, I now realize Kylie is taller, bigger boned and stronger than I had expected. I also finally understand her attraction to her husband, Jack. Like her father, he is of the earth and sun, but unlike Sean, his spirit is restless and ridden with self-doubt.

Later that evening in a tavern, I notice a painting of a ship with a female masthead, a mythological being of beauty and strength that guides the vessel over glistening waters. At once I imagine Kylie at the helm with her shoulders wide, riding the waves above the sea’s ebony abyss. She keeps her focus locked on the horizon, instinctively knowing if she loses sight of it her world will drown in the undertow of darkness. In the next moment, I see a random flash of Kylie’s past—she is clutched in the arms of her mother deep in the subway, the lull of the train calming her colic.

It is not until my story takes me to South Boston that I finally see Kylie whole. From the train station I begin walking toward the sunset, uncertain of my destination. After a few blocks, I am drawn to a grade school with its empty playground. When I explain that I am a writer, a kind principal allows me a walk through the abandoned hallways. It is in the shine of the floors that I see a reflection, a seven-year-old girl skipping along with pigtails and singing a dainty melody. Her back is to me, yet I recognize her from thirty feet away. She never turns around yet the image brings a whole young narrative to life. One of a spirited protagonist who remains apart, lost in her own world. At last the floodgate opens and I understand the dark current that has run beneath Kylie’s character all along and realize she is not wholly of this place. The answer waits far down the coast in the Georgia bayou. Kylie has finally claimed her own will and begins to lead me.

It is not until my story takes me to South Boston that I finally see Kylie whole. From the train station I begin walking toward the sunset, uncertain of my destination. After a few blocks, I am drawn to a grade school with its empty playground. When I explain that I am a writer, a kind principal allows me a walk through the abandoned hallways. It is in the shine of the floors that I see a reflection, a seven-year-old girl skipping along with pigtails and singing a dainty melody. Her back is to me, yet I recognize her from thirty feet away. She never turns around yet the image brings a whole young narrative to life. One of a spirited protagonist who remains apart, lost in her own world. At last the floodgate opens and I understand the dark current that has run beneath Kylie’s character all along and realize she is not wholly of this place. The answer waits far down the coast in the Georgia bayou. Kylie has finally claimed her own will and begins to lead me.

As a novelist, location research is invaluable to my process. Not until I breathe in the world of my characters can I get close enough to see the play of sunlight on their lashes. I love nothing more than going out into their worlds, teasing and pulling and coaxing them to life.

In the end, they teach me about myself and my own past. They dig into the shadows and draw out memories, twisting and turning them like old play things, molding and adapting them, disguising them so that even I don’t always recognize them. Still, I catch glimpses of my life in these characters, of my mother and father, my siblings and dearest friends. I see an old professor, a cranky neighbor, and a gay friend who suffered yet triumphed over a brutality. I catch a shy glimpse of my mother in Lila Gascoyne as she covers her mouth and glances away.

In following Kylie through the seasons and years, a lifetime of relationships has formed. These characters have become a part of my being, their lives so intertwined with Boston in my mind, that the city and Quietus are now synonymous, one ceasing to exist without the other. I have walked in their streets, visited their bars and workplaces. After stalking them through their subways, spying at their doorways and even slipping into their beds, they have become so real to me that I don’t want to let them go.

In a writer’s admission of madness—an expansive place has been forever carved into my memory, one where the characters of Quietus continue to live and thrive long after their last scenes have been written. Though I am not there to bear witness, they carry on in a parallel plane of existence where I half believe if someone looks close enough they will see them.

—

Vivian Schilling is the author of the acclaimed novels Quietus and Sacred Prey, as well as a screenwriter, producer and director of independent films. She recently completed work as co-writer and producer of the French documentary “Bonobos: Back to the Wild” and is currently at work on her third novel. For more information visit www.vivianschilling.com.

Category: On Writing

Quietus was such a great story and this article by Vivian was wonderful to read. Thank you Vivian and I eagerly (and patiently) await your next novel.

Thank you, Tom. I appreciate your kind thoughts and encouragement.