Reaching Back and Recovering Women’s Voices

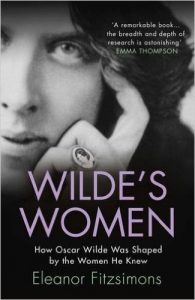

My passion is bringing women back from the past. I wrote Wilde’s Women when I realised that (male, for the most part) biographers had largely ignored the brilliant women who helped make Oscar Wilde the man he was.

My passion is bringing women back from the past. I wrote Wilde’s Women when I realised that (male, for the most part) biographers had largely ignored the brilliant women who helped make Oscar Wilde the man he was.

That’s why, last Saturday, 26 November, having spent two intensive days sitting in a lecture theatre in Kingston University, Surrey, England, listening to a parade of eminent philosophers and psychoanalysts speak with great passion about their respective fields, I stood up to deliver a paper of my own.

‘Oh you’ve really done it this time,’ said that nagging little voice in my head. ‘What on earth are you doing standing here, so far out of your depth, among experts in fields you know practically nothing about’? In response, I did what we should all do. I ignored that voice and started speaking.

Admittedly, I really don’t know a whole lot about philosophy or psychoanalysis. Fortunately, the title of the conference was ‘Nietzsche, Psychoanalysis and Feminism’, and I do know plenty about that last one. More importantly, I know more than most about proto-modernist writer George Egerton, who wrote Keynotes, a hugely popular collection of short stories published in 1893, and who, in this and in her follow-up collection, Discords, was one of the very first people to engage with and refine the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly his pronouncements on women. If you don’t know her, I wrote about her on my blog. I’ll summarise her importance here.

Egerton was born Mary Chavelita Dunne in Melbourne, Australia, in 1859, to Isabel George, a Welsh Protestant, and Captain John J. Dunne, an Irish Catholic. A militiaman’s daughter, her unsettled childhood unfolded between Australia, Chile and New Zealand. She was also educated for a time in a German Catholic boarding school. The early death of her mother, when she was just fourteen, obliged her to abandon aspirations of becoming an artist in order to spend her formative years in and around Dublin, helping her widowed father raise her younger siblings. As a result, she considered herself ‘intensely Irish’.

In adulthood, Egerton lived for a time in Norway. A talented linguist, she learned Norwegian and also studied the writings of Nietzsche in German a decade before he was translated into English; she incorporated his ideas and her response to them into her experimental and provocative short stories, and in doing so offered what is now recognised as ‘a sustained and intelligent response to Nietzsche’s philosophy, and in particular to his take on women’.

In her interlinked stories, Egerton explores the gradual acceptance by her female protagonists that the purity required of them was a patriarchal construct imposed in order to deny them sexual freedom and fulfilment. In ‘Now Spring Has Come’, she is scathing in her criticism, writing:

Men manufactured an artificial morality; made sins of things that were as clean in themselves as the pairing of birds on the wing; crushed nature, robbed it of its beauty and meaning, and established a system that means war, and always war, because it is a struggle between instinctive truths and cultivated lies.

Her women reject their prescribed roles as guardians of morality. Instead, they cooperate with other women, often overcoming constructed ethnic and social divisions in pursuit of agency and self-determination. ‘Woman, where her own feelings are not concerned, will always make common cause with women against men’, she wrote in ‘The Spell of the White Elf’, the third story in Keynotes.

George Egerton

The fact that the women in Egerton’s stories express sexual desire led to her being classified as an ‘erotomanic’ alongside Wilde and Ibsen. Her fictional world was described as ‘topsy-turvey’; Punch parodied her viciously; and The Pall Mall Gazette refused to quote from Keynotes ‘for fear of giving to this book an importance which it does not merit’.

Her engagement with Nietzsche was used against her too; she was accused of being in thrall to ‘a German imbecile who, after several temporary detentions, was permanently confined in a lunatic asylum’. Yet, her friend Laura Marlow Hansson recognised Keynotes as a book intended for women’s ‘private use,’ and understood that it was ‘not addressed to men and it will not please them’. Egerton’s value to us, writes literary scholar Dr Tina O’Toole, is that she ‘created the intellectual and aesthetic space for early feminists to explore theoretical perspectives and to invest in themselves’.

Although Egerton wrote five short story collections, an epistolary work, one novel, and several plays, she never replicated the success of Keynotes. She spent the final four decades of her long life in relative solitude and died in 1945. As one obituary writer put it:

George Egerton’s death brings back to mind the so-called ‘new woman’ school of fiction of the nineties in which the ‘problems’ of the relations of the sexes for the first time in English literature were put before a somewhat bewildered Victorian public.

After I delivered my paper, I put my notes aside and explained why I was there. ‘We’re always wrestling with Nietzsche’s misogyny,’ I said, ‘and qualifying our condemnation by reminding ourselves that he was a man of his time. Well, here is a woman who lived when he lived, who read his work while he was alive and who commented from the perspective of someone who knew exactly what society was like back then’.

Happily, all those lovely philosophers and psychoanalysts approved. Although most had never heard of George Egerton before I spoke to them, all agreed that she was indeed important to the study of Nietzsche, and of Freud, whose ideas she also engaged with. They thanked me for bringing this very important woman to their attention and, best of all, the wonderful Christine Battersby, a leading feminist philosopher, mentioned in her keynote speech how pleased she was that George Egerton was included on the programme.

Over the course of history, women’s voices have been suppressed, ignored and forgotten about to a far greater extent than their male counterparts. Yet, these women were not silent in their day: they were writing, publically and privately; speaking out even when this brought condemnation down on their heads; and reacting to male thinkers in very significant ways.

There is an onus on us to ensure that their voices are recovered and their ideas rehabilitated. If we fail to do this, we lose a crucial part of our history and run the risk of having our voices forgotten too.

Here in Ireland a strong movement with a stated aim of recovering women’s voices is emerging. In the past twelve months, The Long Gaze Back and The Glass Shore, two brilliant anthologies of short stories written by Irish women, past and present, and edited by champion of literature Sinead Gleeson, have been published by New Island.

Here in Ireland a strong movement with a stated aim of recovering women’s voices is emerging. In the past twelve months, The Long Gaze Back and The Glass Shore, two brilliant anthologies of short stories written by Irish women, past and present, and edited by champion of literature Sinead Gleeson, have been published by New Island.

Both have sold extremely well and each was deemed ‘Best Irish-Published Book of the Year’ at the Irish Book Awards. Several of the women featured also appear in Wilde’s Women but their work had not been in print for decades. A new Irish independent publishing company called Tramp Press has produced the first two books in its Recovered Voices series: The Uninvited by Dorothy Macardle and Orange Horses by Maeve Kelly. Both are brilliant and deserve to be read.

In November 2015, responding to the launch by the Abbey Theatre, Ireland’s national theatre, of its programme to mark the centenary of the 1916 Rising, in which only one out of the ten plays programmed were written by a woman and three out of ten were directed by women, a grassroots organisation called Waking the Feminists held a public meeting calling for change. The success of this group has been phenomenal and their energy is unfailing.

I’m lucky enough to have been involved in several events organised by the brilliant Herstory, which describes itself as: ‘A new cultural movement that will tell the lost stories of hundreds of Irish women from history and today’. Their Culture Night event in 2016 attracted a huge crowd of hip young women and men who queued in the cold, waiting to get in. I’ve also written guest posts for the brilliant Sheroes of History, a project run by Naomi Wilcox-Lee in the UK, and I’ve contributed profiles of forgotten literary women to USA based Professor Anne Boyd Rioux’s Bluestocking Bulletin.

It’s genuinely exciting to see the emergence of such a plethora of books, projects and organisations dedicated to recovering the voices of forgotten women. The benefits of getting involved, or taking the initiative to set something up, are enormous – participation allows us to promote our own writing, to connect with like-minded people, and to be inspired by the tenacity of some amazing women from history.

So, look around you. What can you do to help?

Why not start by reading some of the brilliant books by women that have been allowed to fall out of circulation? Many are out of copyright and available free on-line at www.archive.org or www.gutenberg.org. These women deserve to be heard.

—

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing