Rethinking Structure

In the light of the recent sexual misconduct cases, I have been questioning again the way that we tell story. The hero’s journey, taught on so many creative writing MFAs the world over, is still our go to method for structuring our story. It is either an inward journey or an outward one.

In the light of the recent sexual misconduct cases, I have been questioning again the way that we tell story. The hero’s journey, taught on so many creative writing MFAs the world over, is still our go to method for structuring our story. It is either an inward journey or an outward one.

We walk with characters through the journey, hitting each point as they go: they live in the ordinary world, they are called to adventure, they refuse the call, the mentor arrives. If you haven’t heard of it, look it up.

When I taught it, the two examples I would use were the classic ‘Lord of the Rings’ plus – I would ask each student to write down a favourite film or book on their pad, and then as I followed the journey through, I asked them to peg the journey of their story to it. It works. It is with sad weariness that I say this.

When I was published, I wrote a book of connected short stories. I wrote them in this way for a very specific reason: I had studied the structure of the hero’s journey and in my simplistic manner, had conflated it with the singular journey that we were being peddled by big business. We must be selfish and move forward within our own lives ambitiously, in order to achieve individual success. This had influenced art and film to the extent that the movies I had seen for fifteen to twenty years had started to sicken me: film after film about white males dominating and winning.

Women were handmaidens to the achievements. The biggest franchises in the world were being reinvented: Bond, Batman – though at their helm was still, a white male, helped by clever women (the concession to the modern age).

Literature and the art of writing could and is flouting this system. With my own book, I decided to write about various characters from one community, so that eventually my book would be a village, newly made, in London. It was ambitious, but received well. However, when trying to write the longer work next, I have stumbled and failed, over and over again. I have written five drafts of one novel and two of another, and all have failed. I cannot write a singular journey, it seems. Maybe being brought up by a socialist, feminist father has gone so deep I can’t be swayed?

This structural impasse has caused me to pause and look at the world. Structures are everywhere, and have become the sharp focus of what we do and how we do it. The internet and our usage of it is laid out in structural patterns. The way we click from one thing to another, the way we get a sugar high when someone likes something we have said (or weirdly, a picture of our face) on whichever social media platform we use, is all calculated by the businesses – Facebook, Twitter etc. – that designed structures that would keep our attention.

The way this clicking through undermines my ability to concentrate on one thing – click, click, click is disquieting. It has infected every strata of life: the political, with President Trump tweeting or our own MPs sacked for trolling, to our young people’s mental health affected. And what does it do to us, the writers, the thinkers?

Weinstein and his business tribe had remade our viewpoint on how films should be structured. If the storyline did not follow the hero’s journey rigidly, we used to not like it: we were so conditioned to understand a singular person’s journey. However, recently, the Marvel comic storylines have expanded, so that (now the singular journeys have been exhausted) the heroes work collaboratively. Netflix and other TV makers are churning out series after series of shows about more than one character, and they’re often not male or white. We are voting with our discernment and buying into the world of multiple character, multiple viewpoint.

This is the brave new world, I think. Art is political, whatever we think to the contrary. When we write, when we read, when we watch film or TV, we can subvert what big business wants from us. We can subvert what Weinstein and his merry band have wanted to do to our culture – to demean women and put them in supporting roles to the singular male journey. We can rebalance the inequality that has been peddled to us for so long.

Thinking expansively – sideways, along the well travelled road – is the way forward for all of us, I think. Audiences are being reconditioned. Of course, the hero’s journey is applied to each individual character – but there is a shift in the way sub plot characters are simply serving the main characters: the sub plot characters are easily as important as the protagonists, now. Everyone is a protagonist. When Rose McGowan opened the floodgates and the MeToo hashtag strengthened, each individual story became important – as if collectively, we rose up and said – my story is as important as yours, and no matter how much money or power you have will not stop me telling it.

To see the world clearly for what it is is the gift of our age. We will see that there is room for all stories. It is such a hopeful time. All of the old structures are falling, and in their place is the new, more expansive world that is reflective of all of us. These are the books I want to read. These are the films I want to see.

—

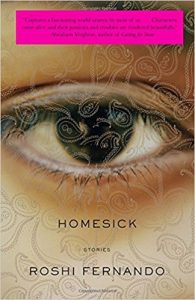

A stunning work of fiction about contemporary immigrant life from a dazzling new writer.

A stunning work of fiction about contemporary immigrant life from a dazzling new writer.

It’s New Year’s Eve 1982. At Victor and Nandini’s home, family and friends gather to celebrate. Whiskey and arrack have been poured, poppadoms are freshly fried, and baila music is on the stereo. In the middle of it all is sixteen-year old Preethi, tipsy on youth, friendship, and pilfered wine, desperate to belong. Moving back and forth in time, between London and Sri Lanka, and circling the people in Preethi’s world, Homesick is a poignant narrative that blends love with loss, politics with pop culture, and tradition with rebellion.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing