Revising for Tone During Difficult Times

Revising for Tone During Difficult Times

Revising for Tone During Difficult Times

By Katherine Cowley

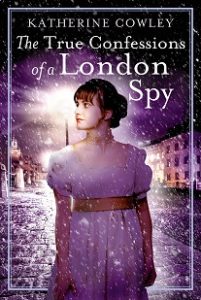

I spent most of 2020 writing and revising my novel, The True Confessions of a London Spy. It was a difficult book to write for all the reasons you would expect…shutdowns, school closures, family worries, life upheavals, the rising pandemic death toll, and sickness spreading, spreading, spreading.

Somehow, I finished a third draft of the book and sent it to my literary agent, Stephany Evans. She told me the mystery worked, the characters worked, the relationships worked, the setting worked, the structure worked…but I needed to shift the tone of the first half of the novel. She wanted the first half of the book to have a lighter, more upbeat, and more hopeful tone.

I agreed with her reasoning, but this left me with two problems.

Problem 1: Tone felt like a nebulous entity. While I could give a basic definition for tone, I didn’t really know what tone was.

Problem 2: I had written this book during a pandemic, and there was no end to the pandemic in sight. How do you write in a tone—or revise for a tone—that is anything but what you are feeling or experiencing during your own life?

*****

In writing, tone is often equated with attitude. Scott Ober says that “Tone…refers to the writer’s attitude toward the reader and the subject of the message. The overall tone of a written message affects the reader just as one’s tone of voice affects the listener in everyday exchanges.”

In essay writing—at least in the sort that I teach in the first-year college writing classroom—tone is often talked about in terms of registers. You can choose a formal tone (which uses more complex words and has more complex sentence structures), an informal tone (like a text message), or a tone that’s somewhere in the middle. Yet none of this knowledge seemed helpful for my current revision task.

I knew tone could be impacted by word choice, sentence structure, voice, point of view, and stylistic choices, but it all seemed very abstract…how exactly did one go about shifting the tone of a story?

Still not quite understanding the definition of tone, I analyzed the first chapter of my book. My main character, Mary Bennet (of Pride and Prejudice fame), has an appointment with a dead body. Halfway through the first chapter, Mary views the dead body, and she feels so ill and disturbed that she has to leave the crime scene for a few minutes to compose herself. This early failure is essential for her character arc—it gives her a greater capacity for transformation and growth. After all, it’s her first official case as a spy for the British government, and the story is about her proving herself, realizing that she can do the job and do it well.

Yet the first chapter of the book read like my experience of March through June of 2020. Terribleness was everywhere, outside and in. I knew it. My family knew it. The news knew it. And my story knew it. I knew that Mary would have a failure in this chapter and that this would haunt her the rest of the book. And the chapter read that way.

I decided to keep the dead body—my novel is a murder mystery, after all. And I decided to keep the failure. However, I also added a new scene at the start of the chapter, introducing the spies and their relationships in a lighter way. Instead of going directly to intensity—stress as they are headed to see a dead body—my characters compete in a word game as they watch snow falling outside the carriage. There’s a playfulness to the interactions between Mary and her fellow spies; we see their personalities and the energy of the moment.

This shifted the tone of the entire chapter, and shifted the attitude the narrator has toward Mary, by choosing what to focus on. It also shifted Mary’s attitude toward her failure. My novel is in close third person—we’re going deep into Mary’s head and perspective—so the tone is naturally going to align closely with Mary’s own attitude towards events. By starting with a lighter, more playful scene, Mary is able to bounce back more quickly after her failure—she returns to the crime scene with less doom and gloom, and more of a desire to prove herself.

The second chapter introduces the major subplot: Mary Bennet’s relationship with her family. In Pride and Prejudice, Mary’s older sisters, Elizabeth and Jane, are close friends, as are her younger sisters, Kitty and Lydia. Mary isn’t close to anyone. At various points, her sisters mock, tolerate, or ignore her. In The True Confessions of a London Spy, I wanted to explore the question: can Mary develop positive relationships with her family members?

Yet the trouble with my second chapter was that Mary knew she had terrible relationships, and this led to this very negative tone. In order to have a transformation, I did need to create room for her relationships to grow, but even if I set up the relationships as inadequate, I didn’t need to use a tone of pain.

I added tiny moments of joy and levity to the chapter—while talking with her family, Mary finds joy as she draws a picture of her aunt, Mrs. Gardiner. There is an amusing moment for the reader when Mary can’t figure out what to do when she has pencil lead all over her fingers.

I also shifted how she interprets the events of the chapter. Mary learns that her sister Jane is pregnant, and everyone else in the family already knew—everyone had been told but her. Before I revised for tone, this was Mary’s reaction:

“Oh,” said Mary. She turned her face to the fire to hide her disappointment that no one had told her the news. “I did not know.”….

This was not the first time people had forgotten to inform Mary of something important. When she was nine years old her grandmother had died. Mrs. Bennet had locked herself in her room for two days, but as that was a somewhat regular event, Mary had continued to focus on her books and not inquired as to the current cause of Mrs. Bennet’s affliction. Her family had already been wearing black in remembrance of a friend in Meryton who had recently died, so there had been no visual signal to cue Mary to the event. Only when her mother decided to again show her face to the world did Mary find out, though her sisters had been informed the moment the news arrived at Longbourn. Mary shut her eyes tight and breathed deeply. She blinked several times, composed her face, and turned back toward the others.

“That is quite exciting for the Bingleys. I am sure Jane will make a wonderful mother.” She swallowed, and then, because she felt obligated to say something more, she recited the only passage about motherhood that she could quickly bring to mind.

In the next draft, I kept the events of the scene: Mary still discovers that she is the only one who didn’t know that Jane was pregnant. But I largely rewrote the passage:

“Oh.” Mary turned her face to the fire to hide her disappointment that no one had told her the news. “I did not know.”….

This was not the first time they had forgotten to inform Mary of something important. Once her family had even managed to not inform her of her grandmother’s death for an entire week. If Mary did not know better, she would think there was a secret competition amongst her family members to keep things from her. It would not surprise her in the least if she were the last person to find out that she herself had become engaged or died.

Mary turned her focus back to the drawing of her aunt. The conversations began to ebb and flow around her, but she did not attempt to join any, savoring instead her little island of solitude.

I ended up making hundreds of changes, big and small, throughout the first half of the novel. Doing so transformed not just the tone, but the novel as a whole. Mary has some dark moments in the middle of the book: terrible things happen, and she blames herself. By shifting the tone in the first half of the book, it not only made the story lighter, more entertaining, and more engaging, it also meant that Mary had farther to fall when she reaches her lowest point. And then, as she rises to a higher point by the end of the novel, we can see the contrast between the beginning of the book—where the tone is light, but much of Mary’s future is unsure—and the end of the book, which culminates in a tone of confidence and joy, with Mary happier with herself and her relationships.

As I revised, I realized that tone truly is attitude—it’s the narrator’s attitude towards and relationship with the subject matter, a lens of interpretation which effects the emotional feel of the book for the reader.

Revising for tone did not just change my book. It also changed my own relationship with my own life. As I looked at Mary’s circumstances and struggles through a new lens and with a new focus, I was able to shift the way I looked at my own circumstances and struggles, to see them with a lighter, more upbeat, and more hopeful attitude.

—

Katherine Cowley loves reading Jane Austen novels, eating chocolate, and visiting national parks. She teaches writing at Western Michigan University and is the author of the blog Jane Austen Writing Lessons, which was selected by The Write Life as one of the 100 Best Websites for Writers in 2021. Her debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, was nominated for the Mary Higgins Clark Award. Her second novel, The True Confessions of a London Spy, continues Mary’s adventures.

Social Media Links:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/KatherineCowleyBooks

Twitter: https://twitter.com/kathycowley

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kathycowley/

THE TRUE CONFESSIONS OF A LONDON SPY

No one said being a spy for the British government would be easy.

No one said being a spy for the British government would be easy.

When Miss Mary Bennet is assigned to London for the Season, extravagant balls and eligible men are the least of her worries. A government messenger has been murdered and suspicion falls on the Radicals, who may be destabilizing the government in order to compel England down the bloody path of the French Revolution.

Working with her fellow spies, Mr. William Stanley and Miss Fanny Cramer, Mary must investigate without raising the suspicions of her family, rescue her friend Miss Georgiana Darcy from a suitor scandal, and solve the mystery before anyone else is harmed—all without being discovered, lest she be exiled back to the countryside.

This is the perfect job for a woman who exists in the background. Can Mary prove herself, or will this assignment be her last?

https://www.amazon.com/True-Confessions-London-Spy/dp/1956387234/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers