The Importance of Writing Nonsense

Not long before we were married, my husband and I found ourselves chaperoning a road trip with a group of high school students. My grandmother, now deceased, had been kind enough to send along some homemade goodies for the journey. Two rest stops into the trip, my husband lifted the lid on Grandma’s Tupperware to find a batch of scotch bars, a delicious butterscotch version of Rice Krispie squares.

Not long before we were married, my husband and I found ourselves chaperoning a road trip with a group of high school students. My grandmother, now deceased, had been kind enough to send along some homemade goodies for the journey. Two rest stops into the trip, my husband lifted the lid on Grandma’s Tupperware to find a batch of scotch bars, a delicious butterscotch version of Rice Krispie squares.

He took a big bite. Then surprise overwhelmed his features as he sprinted for the nearest trash can to spit it back out. In front of a bunch of laughing teenagers my soon-to-be groom exclaimed, “Oh, it tastes like feet!”

That was the day he came to understand a truth every member of my family already knew: Grandma was a terrible cook.

My grandmother had many gifts. She was smart and witty, kind and loyal, but she was never good with food. Without fail she purchased the worst version of every ingredient, tried the strangest combinations, and made the most awful substitutions. On this occasion, she’d forgotten to buy marshmallows, but happened to have a bag of circus peanuts handy.

The great circus peanut incident has since been absorbed into family lore, a place where many such tales reside, contributing to the kind of communal family experience that produces meaningful glances and inside jokes, which might appear to the uninitiated as nonsense.

As a writer who dabbles in history both from the perspective of fiction and nonfiction humor, I have come to view the stories I pen in a similar way. Filled with specific dates, unique names, and verifiable details as history may be, the moments I find most intriguing and strive to inject into my work are the nonsensical ones.

While writing humorous essays about historical people and events, I am mindful that when we read history, we are absorbing the narrative of the human family. If anything can be learned from the surge in fascination with ancestry research and DNA analysis, it’s that many of us recognize the family stories that came before the one we’re now living still matter.

Ingrained in us is a desire not only to know what came before us, but to become intimately connected with the people who lived the lives that impact our own. My intention when writing humorous, historical essays is to evoke in the reader a sense of belonging to the story, of getting the joke, of being privy to the nonsense, because the people of the past were, in many ways, much like the people of today.

When I share the story of John Joseph Merlin, the eighteenth century inventor often credited with the creation of the first roller blades and, perhaps not surprisingly, the first big inline skating accident in history, I pair that with a tale of my own trepidation at accompanying my children to their first elementary school skate night event.

The shadow cast by my own fears of broken bones and any accompanying ridicule will certainly not find a place in the history books. No one hoping to learn about the many impressive works of Merlin, a talented clockmaker and inventor of musical instruments and automatons, would care about my silly parenting woes. Yet it is anecdotes like these that encourage connection.

When I embarked on writing historical fiction, I came to realize the process is similar. Though I am not injecting myself into history in the same way, I am situating characters with intention. Some are pulled from history while others are placed there by me, but all must become familiar to the reader. Research into the past can only provide a limited understanding of all that transpired around an event. Getting the details correct, or as nearly as possible given the amount of information available, may be critical to establishing credibility as an author, but the part of a story that sweeps a reader away into another world rarely has much to do with the facts.

Instead, it is the way a reader recognizes the familiar in the narrative that matters most, regardless of how distant it may initially seem when viewed through the lens of centuries. When the deep, longing of a character jumps from the page into the heart of a reader who identifies with the emotion, then the facts of history become internalized and the story of the human family carries on.

The moments of this magical connection don’t occur in the facts but rather in the nonsense. They happen in the inside jokes and shared experiences of humanity: the meaningful glances, the embarrassing gaffes, the ill-considered substitutions of circus peanuts for marshmallows. They happen when we see in the characters, whether real or fictional, the truth of the human condition that forms the frame of all our experiences.

The stories we tell, be they ripped from history or set on a faraway planet in the distant future, must include a touch of nonsense.

—

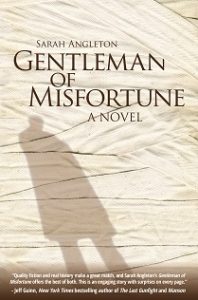

Sarah Angleton is the author of the essay collection Launching Sheep & Other Stories from the Intersection of History and Nonsense, and the historical novel Gentleman of Misfortune. She lives with her husband, two sons, and one loyal dog near St. Louis, Missouri where she loves rooting for the Cardinals, but doesn’t care for the pizza. Keep up with her blog and other happenings at www.Sarah-Angleton.com.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sangletonwrites/

Twitter: @SarahAngleton

Instgram: https://www.instagram.com/angleton.s/

Gentleman of Misfortune in the tale of nineteenth-century gentleman swindler Lyman Moreau, who finds his next big scheme and loses his heart amid a shipment of mummies bound for the most successful prophet in US history.

Gentleman of Misfortune in the tale of nineteenth-century gentleman swindler Lyman Moreau, who finds his next big scheme and loses his heart amid a shipment of mummies bound for the most successful prophet in US history.

“An engaging story with surprises on every page.” —Jeff Guinn, New York Times bestselling author of The Last Gunfight and Manson

“A dark tale of intrigue, mystery, and forbidden love.” —Pat Wahler, award winning author of I Am Mrs. Jesse James

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

I almost sprayed my computer over the “feet” story. Great thoughts on writing historical fiction and keeping the humor in life.

It was always a bit of a risk eating at Grandma’s house. 🙂