The Process of Writing A Memoir by Kathryn Gahl

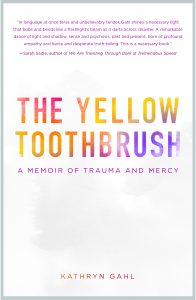

From award-winning Wisconsin-based poet and fiction writer Kathryn Gahl (The Velocity of Love, Messengers of the Gods) comes THE YELLOW TOOTHBRUSH, a poetic memoir that delves deeply into the many facets of motherhood: tragic loss, brave resilience, and unconditional love.

In THE YELLOW TOOTHBRUSH (Two Shrews Press, August 30, 2022), Kathryn Gahl offers a stunning look at anxiety, depression, OCD, and paranoid thinking through the eyes of a mother whose daughter is experiencing the unimaginable: a jail sentence after committing filicide. Postpartum depression and anxiety remain widely misunderstood conditions in modern society, and through THE YELLOW TOOTHBRUSH, Gahl sheds light on these mental disorders in hopes of helping families in the future.

In THE YELLOW TOOTHBRUSH (Two Shrews Press, August 30, 2022), Kathryn Gahl offers a stunning look at anxiety, depression, OCD, and paranoid thinking through the eyes of a mother whose daughter is experiencing the unimaginable: a jail sentence after committing filicide. Postpartum depression and anxiety remain widely misunderstood conditions in modern society, and through THE YELLOW TOOTHBRUSH, Gahl sheds light on these mental disorders in hopes of helping families in the future.

In this striking collection of poetry, Kathryn Gahl graciously shares details of her daughter’s pain and suffering that led to the loss of Gahl’s own grandson via filicide. She writes of visiting her daughter in prison and in words too deep for tears relates the realities and consequences of a brokenhearted family. What happens to us when mental illness puts our loved ones in prison? What questions do we ask ourselves when their illness results in personal tragedy, and incarceration is their fate? How does a mother move forward, putting the love of her daughter above her actions and afflictions? For Kathryn Gahl, there is no other option than to fight for her daughter’s freedom, both physically from her jail cell and mentally from the disease that took over her being.

The Process of Writing A Memoir

by Kathryn Gahl

August 2022

I had no idea I was writing a memoir when words burst out of me, phrases, raw facts, bloody emotions. I was simply doing what I’d done for decades: put art to work when things got tough. My son’s basketball coach would say, quick feet, make an adjustment.

Yet, here was an adjustment more important than winning a basketball game; I was in the game of life, without a playbook. As nurse and writer, I knew about the workings of the mind, how better writing came from the subconscious—I don’t know what I write until I write it—but the best writing came from the unconscious, the unknown, the dark shadows, the fears that affect us all. Still, how could my unconscious write about the unconscionable, a calamity that had landed my daughter in prison?

I had to get out of the way, smash my ego looking for shame or blame, and shatter the real bugaboo: my rational mind looking for A Reason. Because with mental illness, there is not A Reason; there are a thousand reasons, maybe a galaxy of reasons randomly lining up to explode.

Could I follow the explosion, explain it? Would it matter? Compelled, I wrote snippets, with no goal except to emerge from the hole I was in. When I would climb out of one hole, I would fall into another. What could I do but write, write, write, sometimes badly. Mostly, honestly, badly. Because as the next hole cracked, interstellar dust would settle in the vacuum of space called my brain. Vacuums sucked at my entire being, wrists, ball-and-socket hips, hinged joints coming unhinged. The most dramatic were in my legs, calves attacked by muscle spasms that recurred for months despite a gifted manual therapist dissolving the knots.

Finally, I asked him, what’s going on with my legs.

You are struggling to walk into the future, he said.

It was so obvious, but I needed him to enunciate it.

Legs carry us forward in life, he said, adding, life is for you.

It is? It was? A life of grief and disbelief? After a year of volleying with words, I took a memoir class, thinking I needed to learn how to organize the heap. I read The Art of Memoir by Mary Karr. Diligently, I completed class assignments on structure and shape. None of it worked and I decided to forego a finished piece. My story was too big, layered, and convoluted. It had no clear beginning, middle, or end. And then I recalled a basic tenet I had learned from Frank Conroy in his Fiction Intensive: strive to write with meaning, sense, and clarity.

I looked at my mess and began to revise. Writing is rewriting. Doing so gave me emotional distance as I replaced my writer hat with my editor hat for something I had never written. Nonfiction. I was a fiction writer who had taken a few poetry classes to write ‘word pictures.’ It had been fun and liberating to paint on the page, experiment with white space, line breaks, and sorry Sister Oliver, incomplete sentences. To write one true sentence, Hemingway said, was the challenge. I picked up the gauntlet to write true, complete sentences or not. The higher your structure is to be, wrote St. Augustine, the deeper must be its foundation.

I still did not know the structure, but with an editor’s eye and ear, I could build a foundation of meaning, sense, and clarity. Simultaneously, how could I manage time? The passage of time in telling a story can be circuitous, confusing, or used effectively to build tension and forward motion. What structure would work for this? In memoir, Karr wrote, the heart is the brain. My heart was broken and my brain was mush. In that muddied state, I stopped seeking a shape or structure, probably because I still did not know I was writing Something Big. Say, a book. I was only writing about worlds heretofore unknown to me as I scribbled on yellow pads, jotted notes while driving, scrawled on tear-stained pages. As the pile grew, I typed them up, printed them, and was reminded, once again, of the need for a beginning, middle, and end, which in turn spun the merry-go-round toward the necessity of a structure or a shape.

Experimentation followed, but no structure seemed to work, whether prose, chapters, prose poems, narrative prose, hybrid, cross-genre, flash, vignettes, epics, linked stories, or elegies. There were no shape templates for me either, whether chronological, time-travel, backwards in back story, spiral, punch-to-the-gut present, or admixtures of circumspection and candor. I felt frenetic and vulnerable. I knew that I could not know what I did not know. And so, I gave up.

And, seriously, a new form surfaced, nameless, with brush strokes of chaos and calm. Call it touched by the angels or the feminine divine—an aura of mystery touched me, tapping the source of creativity. It was the silence of a human soul wanting only to be heard. And I listened.

—

Kathryn Gahl holds dual degrees in English and nursing. Her works appear in three anthologies, four ekphrastic art shows, and over fifty journals, with awards from Glimmer Train, Margie, Chautauqua, Rosebud, The Mill, Talking Writing, The Hal Prize for Fiction and Poetry, New Millennium Writings, and Wisconsin People & Ideas.

A Pushcart nominee, she served as Writer-in-Residence at Lakeland University. In 2019, The Council of Wisconsin Writers presented her the Lorine Niedecker Poetry Award and in 2021, THE VELOCITY OF LOVE (Water’s Edge Press, 2020) received an Outstanding Achievement Award from the Wisconsin Library Association.

Category: On Writing