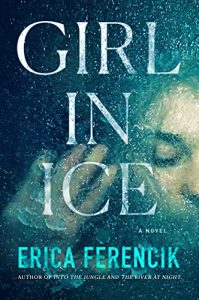

The Story Behind the Story of Girl in Ice By Erica Ferencik

The Story Behind the Story of Girl in Ice

By Erica Ferencik

Photo by Kim Borovik

Like a lot of novelists, I write what I’d like to read, what I wish existed in the world but as far as I know, does not. Girl in Ice was inspired by a mingling of five fascinations: a scene from the original, 1931 version of the movie Frankenstein I couldn’t shake, something I witnessed one winter morning, an obsession with writing on the knife edge of what is real and what is not, a love of science and language, and a lifelong enchantment with arctic settings, specifically Greenland.

One of the final scenes in this black and white rendition of Frankenstein has haunted me since the day I saw it, more than forty years ago. Frankenstein’s monster; hunted, bloodied, in despair, has given up on finding any kindness or acceptance from mankind. He turns from the camera and lurches forward into an unforgiving Arctic landscape, a mad blizzard swirling all around him. Slowly, his blocky, ink-black silhouette is devoured by all the ravenous white, and he is gone. This image broke my heart in ways I’m still trying to parse, but I think it has to do with human cruelty, and our intolerance for our own human variety. There is no Frankenstein’s monster in Girl in Ice, but that feeling of desolation and desperation is something I’ve always wanted to render somehow in one of my novels.

The actual spark for the book came one bitterly cold morning in the winter of 2018. I was walking in the woods near my home, and came upon three juvenile painted turtles frozen mid-stroke in the ice along the shallow edge of a pond. They didn’t look alive…but they didn’t look dead either.

It turns out there are some animals (and plants too!) that have this freezing-and-coming-back-to-life thing down. Painted turtle hatchlings, some species of beetle, wood frogs, certain alligators, even an adorable one-millimeter length creature called a Tardigrade or “water bear” that can be frozen to -359C and thaw out just fine. Most of these creatures possess a certain cryo-protein that protects their cells from bursting when they freeze.

It turns out there are some animals (and plants too!) that have this freezing-and-coming-back-to-life thing down. Painted turtle hatchlings, some species of beetle, wood frogs, certain alligators, even an adorable one-millimeter length creature called a Tardigrade or “water bear” that can be frozen to -359C and thaw out just fine. Most of these creatures possess a certain cryo-protein that protects their cells from bursting when they freeze.

A protein that…we don’t possess. Still, the image of a young girl frozen in a glacier in the Arctic popped into my head. From there, I asked myself: How did she get there? What was her story? She became an obsession.

I love any great story no matter where it’s set; however, I’ve got a real soft spot for any novel or film set in a forbidding place, especially the Arctic. I could speculate all kinds of deep psychological reasons for my love of survival stories. Let me put it this way: like so many others, I survived an extremely challenging childhood, and so I have ready access to dread, to feeling trapped, to planning creative ways to survive. In short, my fight or flight hormones remain close to the surface.

To create the language the girl in ice uses, I immersed myself in the sounds and cadences of the living Nordic languages, among them: Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Finnish, Icelandic and of course Greenlandic, in order to get a feel for inflection and tone. I also dove into recordings of Old Norse, the main language of the Vikings, in order to create morphemes, or units of meaning that sounded Nordic, but that were just slightly distinct from known languages, all to create Sigrid’s unique tongue.

Photo by Kim Borovik

What I had to grapple with next was: How would Val, the linguist protagonist, be able to interpret Sigrid’s speech if there was no correlation to any living or dead language? I consulted some linguist friends who said that without any remnants of written language or cultural clues from a society that spoke it – with nothing to go on, basically – you’d have to start with simple nouns, verbs, and concepts, almost like a baby pieces together her language. But for two people to connect, they have to both want to, or need to, and only when Sigrid realizes she must communicate to survive, does she make the effort.

The plot touches on what I call “ice winds,” my own terminology for a kind of wind that freezes people instantly. These don’t exist, per se, but there are such things as katabatic winds; in Greenland they’re called piteraqs: brutally strong winds generated by radically different air temperatures, often barreling down the slopes of mountains or glaciers. I’m not a climate scientist or meteorologist, but I do know that climate change strengthens hurricanes, tornadoes, wind events in general, as well as prompting dramatic swings in temperature, so I thought it wasn’t too far of a reach – for story purposes – to conjecture that deadly ice storms are in our future and might have been in our past.

Finally, Greenland. This is going to sound silly, but what surprised me the most about it was its size; it’s just so vast, and yet so few people live there. Only 57,000 souls – one-tenth the residents in all of Wyoming – call this island, the largest in the world at about a third the size of Canada, home. Most live in Nuuk, the capital; the rest live in towns often with fewer than 300 inhabitants along a three-thousand-mile coastline, mostly on the west side. The ice sheet measures fifteen hundred miles north to south, is two miles deep at its thickest, covers 80% of the land mass, and has been frozen for three million years.

The second thing that shocked me was how close Greenland is to pre-history. As recently as 1950, people lived in sod huts: low, square dwellings built by digging a hole in the ground during the short summer season – plus or minus fifty days – then creating a supporting structure for a roof out of whale ribs or driftwood, finally sealing it with skins, peat and rocks.

And it’s one thing to read that the economy is mostly subsistence hunting and fishing; it’s another to witness it, to read about quotas for narwhal and minke whale, learn what happens when a polar bear is spotted (it’s not gentle), understand that sled dogs are seen as possessions – not pets – that need to be fed. And, sad as it is to witness for someone unaccustomed to this life, it’s cheaper to hunt seal than cough up five dollars for a can of imported dog food.

I hope you enjoy Girl in Ice; that as a reader it pulls you out of your world into another one entirely. More than that, I hope – as a writer – you find joy and inspiration in all of the most unexpected places.

—

Award-winning novelist Erica Ferencik has received glowing critical praise for her literary thrillers featuring women who face extreme physical challenges in nature, even as they grapple with internal struggles. Devoted to authenticity in her craft, Erica spent weeks in the wilderness of northern Maine as research for her debut novel, The River at Night, an Indie Next Pick that New York Times bestselling author Ruth Ware called “raw, relentless, and heart-poundingly real.” For her “hair-raisingly vivid” (Kirkus) follow-up, Into the Jungle, Ferencik journeyed a hundred miles up the Amazon to experience firsthand the lush and perilous Peruvian jungle. Now, inspired and informed by a month-long trip to Greenland, Ferencik sets GIRL IN ICE (Publisher’s Weekly, starred review “Exemplary…Ferencik outdoes Michael Crichton in the convincing way she mixes emotion and science.”) in one of the most unforgiving, unforgettable landscapes imaginable.

GIRL IN ICE, Erica Ferencik

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips

From the author of The River at Night and Into the Jungle comes a harrowing new thriller set in the unforgiving landscape of the Arctic Circle, as a brilliant linguist struggling to understand the apparent suicide of her twin brother ventures hundreds of miles north to try to communicate with a young girl who has been thawed from the ice alive.

From the author of The River at Night and Into the Jungle comes a harrowing new thriller set in the unforgiving landscape of the Arctic Circle, as a brilliant linguist struggling to understand the apparent suicide of her twin brother ventures hundreds of miles north to try to communicate with a young girl who has been thawed from the ice alive.