The Strange and Expansive World of Narrative Craft By Angie Elita Newell

The Strange and Expansive World of Narrative Craft

By Angie Elita Newell

Almost every writer will tell you, you actually spend more time thinking about writing than actually writing. In that strange moonlit landscape an idea dances in the mist, consuming you, it plays like a lucid dream in your head. In this transcendental space you know you have a story.

Almost every writer will tell you, you actually spend more time thinking about writing than actually writing. In that strange moonlit landscape an idea dances in the mist, consuming you, it plays like a lucid dream in your head. In this transcendental space you know you have a story.

I’m trained as a historian, but also hold degrees in English literature and creative writing. As a historian, you work partly as a detective and partly as a storyteller. To be truly good at it, particularly at indigenous studies which has massive genocidal gaps in archiving this history according to Western convention, you need to have a solid imagination.

I would listen to what indigenous elders from all different tribes would tell me, their surreal history exploding in my mind like the thunderbirds they spoke of, whose eyes shot lightning, their wings beating thunder, roaring across the skies protecting, nurturing, guiding.

And then I would read reports written by historical figures such as General Philip Sheridan (March 6, 1831-August 5, 1888) who stated the only good Indian, is a dead Indian, setting the stage for the ideology that set the precedence for the horrific and enduring Indian boarding schools, kill the Indian, save the man.

As my knowledge expanded and I explored the colonial history of North America under the tutelage of a university education, statements like the above cut through to my blood, they stopped my heart, the thunderbird died.

I began to find non-fiction writing limiting. It hindered where my mind wanted to drift to., What would make an individual who finds themselves in a position creating a collective identity be so evil, and what is evil?

The problem was that this historical mindset is still prevalent and still controls and dictates indigenous society across North America, although there are some differences between Canada and the United States the ubiquitous jackboot of oppression stomps on both our faces.

Myself and my family, we’ve all experienced things that no one should ever experience at the hands of a government that keeps on claiming reconciliation, acceptance, and help. Forced sterilization, police brutality, discrimination, rape, children practically ripped from wombs and given to people deemed better parents than those who carried them, children forced to attend schools that were little more than differently named concentration camps, where they were tortured, experimented on, and murdered. This all happened in the twentieth and twenty-first-century. Some of these things happened to me. And they were accepted and encouraged for this simple fact, we are Indians, the only good Indian is a dead Indian, kill the Indian, save the man.

Despite everything I’ve experienced and lived through, my heart is not filled with darkness. As my worldview has expanded I realize great tragedy has befallen this entire earth, regardless of heritage. My ancestors taught us that we are all one, separation based on a concept such as race is an illusion. So I did what any writer would do, I challenged these words with new words, I claimed the thunderbird’s power back.

The Battle of Little Big Horn stood out to me historically. Previous to the mid-nineteenth century we, the indigenous people of North America, had done a relatively good job at standing our ground and held a lot of agency, we openly intermarried and fused Western culture and technology with our own, taking particularity well to the horse and firearms. This fascinated me because although we adsorbed these technologies we interpreted and used them in an entirely different fashion. For example, horses were stabled in colonial society, but under the moonlight amongst the trees with the Indians, the horses never lived in a barn but were allowed to wander, and appeared to not have not run away.

When I started writing this novel I wanted to highlight the differences and similarities and realized the best way to do that was to have different storylines set against one and other, woven together in a quilt of humanity. I wanted to show that we did have and still have agency and the policies of destruction enacted against us are alive and well and still exist in the present.

That is where the third story came from, Nancy. Named after my long dead mother, I had to weave in the American Indian Movement, because just like the pinnacle of the American Indian Wars, the pinnacle of the American Indian Movement culminated in the exact same geological location with the same indigenous people leading, the Sioux. These are a people connected to the creator in such a deep way thunder roars through their soul, they know what is at stake, and they know when to take a stand. That kind of courage and integrity most people can only aspire to, mostly with false words. They lie to themselves and say that they possess these truths. The Sioux and their allies will not only stand in the truth, but they will fight for it.

I knew to portray this integrity I had to write the truth, and this truth is violent. My literary heroes lie in the mist of the first half of the twentieth century, they too were confronted with a violence that sucks the air out of your lungs and were not afraid to bare their souls and share what was illuminated before them. As a young adult, I was lost in utter admiration to the words and works of Wilfred Owen, T.S Eliot and Ernest Hemingway. I connected to them and their stories for I had grown up in the shadow of dark truths, and these writers are all a different ethnicity and gender than I, and to me this demonstrated that art is universal. Art is timeless, it is a snapshot of a moment. In one memory as the reader you learn everything about that person in that memory, and as the reader or viewer you are someone glimpsing at something foreign yet similar to your own existence.

I set out like my literary heroes to produce something parable, with a fluidness guiding you through memories long forgotten, reminding us nothing is ever truly lost. We are still here and this isn’t just our truth and journey, it belongs to everyone, for just like the art I love, humanity it is an interwoven quilt of heartbreak, wonder, and love. Maybe in this violence we can gleam the truth, the only thing preventing us from harmony is ourselves.

—

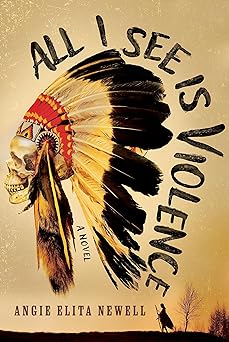

Angie Elita Newell belongs to the Liidlii Kue First Nation from the Dehcho, the place where two rivers meet. A trained historian, she blends a tradition of oral stories with academic history and holds university degrees in English literature, creative writing, and First Nations history with an emphasis on colonialism. Angie is a heavily tattooed global wanderer, a mother to daughters, and a connoisseur of coffee, she has a profound appreciation for humanity and what we as a people can instill upon this awe-inspiring world. She is the author of the new historical fiction about the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn, All I See is Violence (Greenleaf Book Group / January 2024). Connect with Angie Elita Newell at angieelitanewell.com.

Newell is also the co-host of a recently launched podcast, Apparently Transparent, along with co-host and former professional skateboarder, Ross McLeister. Exploring a variety of topics, featuring guests and conversation, this podcast aims to rethinking the human mind and the universe that controls it. This world is large and talk can be small, Apparently Transparent tries to make it big.

ALL I SEE IS VIOLENCE

A woman warrior, a ruthless general, and a single mother―three stories deftly braided into the legacy of a stolen nation

A woman warrior, a ruthless general, and a single mother―three stories deftly braided into the legacy of a stolen nation

The US government stole the Black Hills from the Sioux, as it stole land from every tribe across North America. Forcibly relocated, American Indians were enslaved under strict land and resource regulations. Indigenous writer Angie Elita Newell brings a poignant retelling of the catastrophic, true story of the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn and the social upheaval that occurred on the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1972 during the height of the American Indian Movement.

Cheyenne warrior Little Wolf fights to maintain her people’s land and heritage as General Custer leads a devastating campaign against American Indians, killing anyone who refuses to relocate to the Red Cloud Agency in South Dakota. A century later, on that same reservation, Little Wolf’s relation Nancy Swiftfox raises four boys with the help of her father-in-law, while facing the economic and social ramifications of this violent legacy.

All I See Is Violence weaves love, loss, and hard truths into a story that needs to be told―a journey through violence to bear witness to all that was taken, to honor what all of our ancestors lived through, and to heal by acknowledging the shadows in order to find the light.

PREORDER HERE

Category: On Writing