This Valentine’s Day, Be Glad You Don’t Live In The Times Of Bridgerton…

This Valentine’s Day, be glad you don’t live in the times of Bridgerton…

This Valentine’s Day, be glad you don’t live in the times of Bridgerton…

If you ever write a book, you’ll get used to answering silly questions. As a writer of historical fiction, there’s one in particular that gets me every single time. “Would you like to have lived in the nineteenth century?” people ask me, their voices crackling over the poor Zoom connection. It’s all I can do not to laugh.

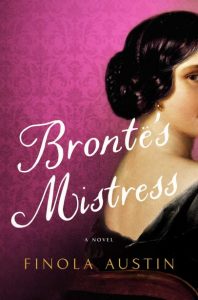

By this point, they’ve usually read my novel, Bronte’s Mistress, or, at least, listened to me talk about it for the best part of an hour. My book is fiction, but it’s based on the true story of an older (read: 43-year-old) woman who had an affair with Branwell Bronte, the Bronte sisters’ (then 25-year-old) brother.

Trapped in a loveless marriage, with no access to divorce, my protagonist Lydia is more privileged than many Victorian women, but still, essentially, powerless. As a woman, her education has been limited, designed only to give her the requisite accomplishments to land a man. As a mother of a certain class, her babies have been taken from her at birth, her breastfeeding discouraged, and her teenage daughters entrusted to the care of another (Branwell’s sister Anne). And, as a wife, her husband has rejected her, giving her no prospect of enjoying sexual pleasure again, without risking her way of life.

Lydia has no money or property, and can’t have a career. She can’t even dye her hair when it starts to turn gray. And it’s not like she can just pop on Amazon to buy a vibrator! Frankly, that’s not the sort of existence I’d be willing to sign up for. Still, I get asked this question. A lot. And the only culprit I can think to blame is the TV costume drama.

Corsets and balls, dressmakers and dance cards. Not to mention dashing, chiselled, and presumably well-showered male leads. Who could resist this vision of the past? The historical shows we’re used to on big and small screens are sanitized. Deep discussion of social inequalities, or details like menstrual rags and body hair, do not swoon-worthy television make. (Note: An early male reader of my novel actually stopped reading in disgust at a reference to my heroine’s leg hair).

But, reader, I must make a confession. It’s very possible to know that the pullout method is unreliable, while still longing to be ravished in a library by the Duke of Hastings. And, in the same way, being a writer of grittier, more “realistic” historical fiction doesn’t preclude me from enjoying the romantic escapism of Bridgerton.

While I wouldn’t advise any woman to jump in a time machine to return to the 1800s, I think there’s an equally important place in the world of historical fiction for romantic fantasies and more critical examinations of the past. This is especially true when alternate histories offer audiences a chance to see a more diverse slate of actors in leading roles (I highly recommend Salamishah Tillet’s article on race in Bridgerton for the New York Times).

So, this Valentine’s Day, don a ballgown, role play, and tell your partner you burn for them, or just snuggle up in front of Netflix with snacks. But know that some fantasies are best left for the bedroom, and be careful what you wish for…

—

Finola Austin is a Brooklyn-based writer of historical fiction. Oprah Magazine described her debut novel Bronte’s Mistress as “meticulously researched” and “in a word, juicy.” It is available in hardcover, ebook and audiobook now. Find Finola online at www.finolaaustin.com

Social Links

www.facebook.com/FinolaAustinWriter

www.instagram.com/finola_austin

https://www.goodreads.com/finolaaustin

Brontë’s Mistress

“My whole life has been waiting. Waiting to be asked, waiting to be visited. Human beings must have action, or they will make it themselves.”

“My whole life has been waiting. Waiting to be asked, waiting to be visited. Human beings must have action, or they will make it themselves.”

Yorkshire, 1843: Lydia Robinson—mistress of Thorp Green Hall—has lost her youngest daughter and her mother within the same year. Now, with her teenage daughters rebelling, her hateful mother-in-law breathing down her neck, and her marriage grown cold, Lydia finds herself yearning for something more.

Change comes with the arrival of her son’s tutor, Branwell Brontë, brother of her daughters’ governess, Anne Brontë, and of those other writerly sisters, Charlotte and Emily. Handsome and romantic, a painter and a poet, Branwell is also twenty-five to Lydia’s forty-three. Colorful tales of his sisters’ elaborate playacting and made-up worlds form the backdrop for seduction, and soon Branwell’s intensity and Lydia’s loneliness find a dangerous match in each other.

Meanwhile, Mr. Brontë has his own demons to contend with, and grave consequences for Lydia’s impudence loom. Her prying servants blackmail her for their silence, her husband becomes suspicious as his health declines, and Branwell’s behavior grows increasingly erratic while whispers of the affair reach his bookish sisters.

With this swirling vortex of passion and peril threatening to consume everything she has built, the canny Mrs. Robinson must find the means to save her way of life, and quickly, before clever Charlotte, Emily, and Anne reveal all of her secrets in their deceptively domestic novels.

That is, unless she dares to write her own story first.

Deliciously rendered and captivatingly told, Brontë’s Mistress reimagines the scandalous affair that has divided Brontë enthusiasts for generations and gives voice to the woman vilified by history as the “wicked elder seductress” who allegedly brought down the entire Brontë family.

Category: On Writing