When a Character Has More to Say

In Virginia City, Nevada, a woman walks into a bar.

In Virginia City, Nevada, a woman walks into a bar.

When she tries to pay for her drinks, none of her credit cards work.

“They all have different names,” says the bartender. “You got any ID?”

“I’m Lianna Dru!” the woman cries. “I’m here for the Boom Town Days and the cast reunion for Silver Sierra, the old TV show. I’m Lianna Dru! Don’t you go to the movies? You must know me!”

That was how I introduced a MINOR character in my novel, Who Have the Power. One of several women with identity issues, Lianna Dru had only a few scenes and a few lines.

I finished that book and moved on to a story about a family with secrets, but Lianna Dru kept popping into my head, insisting that her family, all movie stars, harbored a secret, and it was way better than the ones I was writing about.

Go away! I’m done with you!

As you know, characters don’t always listen. I guess that’s why we call them characters.

So – I listened.

Lianna got me watching movies from the 1930s and 1940s, when her parents would have begun their film careers. Listening to the commentary for The Mark of Zorro (1940), I learned that two cast members’ careers had been cut short by the blacklist, and one had died possibly from the pressure.

Did the Dru family secret have something to do with the Hollywood blacklist?

It seemed so. Because Lianna got quiet.

I didn’t know much about the blacklist, so I started reading and got engrossed and furious about that miserable, senseless, divisive, suspicion-laden part of our country’s history. I hope we never have to revisit that kind of mess again, but it did bring out the best in many people.

I also realized that Lianna’s real name was Dianna Fletcher. (She really had been confused at the bar. Or perhaps I hadn’t heard correctly.)

Dianna Fletcher’s main worry at sixteen, which is when I decided to start her story, was that she would not have the same career her mother had.

She was right.

And the reason she was right had to do with the Hollywood blacklist and the changes in movies and the studios after World War II. These had effects on movie themes and on women’s roles in those movies.

The Golden Age

They call it the “golden age” of movies and “classic” Hollywood,” the time just before, during, and after World War II, when the major studios ran like factories, producing about one film every day of the year. This meant a need for many actors under contract and whole factories of talented artists and crafts people. Studios would train and groom actors, make sure writers would write to actors’ talents, and even pick out a performer’s strongest musical note. Employees had to do what they said – studios figured they owned you – but the strongest stars found a way not to always obey.

Dianna’s parents, the stars John Fletcher and Anne Foster, had worked steadily within the studio system at MGM and Twentieth Century Fox. They were powerful stars, with strong national and international followings.

During World War II, the movies raked in the money. Audiences found both community and a way to escape in theaters. Every studio owned its chain of theaters, and movies poured onto the screens, as did cartoons and newsreels.

But that period wasn’t always “golden.” The studio moguls were lechers and predators on young women and they were deeply prejudiced against African Americans and immigrants. It must be remembered that movies were not inclusive, and people with other than white skin, including fantastically talented artists, struggled to make a living using their talents. Those who made it to the top, like Lena Horne, had to be scripted in such a way that their parts could be cut in southern theaters.

And the long-held prejudice against women in entertainment gave some men, especially the powerful moguls in studios, the belief that they had a right to women’s bodies.

The Production Code

In public, studios waved the flag, mother, and apple pie. During the “golden age,” studios aimed at bringing in a broad national audience for their movies; in other words, the movies couldn’t offend. They had offended for some time before. Movies had started in peep shows, in seedy parts of town, but then grew to the big screen, often sexually frank and exploitive of women’s bodies. Prostitutes didn’t repent. Crime paid. Local censors banned movies, for different reasons depending on the locale, driving the studios nuts. In defense, the movie industry established its own Production Code.

According to a New Yorker article by David Denby (4/25/16),

Producers, directors, and writers were forced to create sex without sex, to produce sexual tension by working around the prohibitions, extending every manner of preliminary to sex. In effect, censorship created plot, and in the process yielded one of the greatest of American film genres: thirties romantic comedy. Sex became play…expressed most romantically, in the movies of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers…

This “sex without sex” had the advantage of strengthening women’s roles. They could be equal to men while the sexual tension rose, heightened through nuance and imagination. Strong women’s roles as well as strong romantic stories appealed to women during the war and brought audiences back.

For several years, nothing could get produced without the Code’s approval. And as much as we can make fun of the Code’s restrictions, the limitations were part of the creation of some multi-dimensional women, even in an industry headed by men: Jean Arthur, Ingrid Bergman, Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Irene Dunne, Olivia de Havilland, Joan Fontaine, Greer Garson, Katharine Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Deborah Kerr, Maureen O’Hara, Barbara Stanwyck, and many others whose names you can supply.

But After the War…

After the war, people went home. Many left the cities and settled in the suburbs. A suspiciously unified campaign encouraged women to leave their jobs to the men and rejoice in the glorious role of homemaker. Men, now on the frontlines in business, went home to dinner and the hearth that featured the new television set. (That is not entirely accurate, but it was the cultural consensus of the 1950s ideal. Many women still worked outside and inside the home.)

That migration and sales of television sets caused movie attendance to drop by half in as little as a year.

That was the first blow to the studios.

There were more: Despite often violent pushback by the studios and accusations of Communist infiltration, unions showed their strengths and gained a hold on the industry. This added to the studios’ costs. Also fighting the unions cost money.

The Supreme Court ruled that studios would have to divest themselves of their theater chains. Without a link between production and exhibition, every movie made became a risk.

The studios cut production, personnel, and departments. They sold off their back lots. They canceled contracts.

Then came the blacklist, and the once powerful studios, who represented the nation to the world, were too weak to defend their own. Eventually, studios would link up with independent production companies, and the men who bought the scripts and brought in the talent would challenge the Production Code, already weakened by a more mature, and diminished, post-war audience.

Then Came the Blacklist

Fear of Communism long predated World War II, and during the Depression, there were those who joined the Communist Party (in California, that amounted to a couple hundred people), or worked with Communists, believing capitalism had failed. The CP also supported civil rights and women’s rights more aggressively than any other organization. Most people left the Party just before or after World War II, disillusioned by tactics. But suspicion against Communists stuck, to be exploited by Joseph McCarthy, the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, and Congress. After the war, the fear of Communism provided another enemy to fight, and the FBI and members of Congress – and business – labeled strikes and union activism as Communist-inspired. The same went for civil rights activists and women’s rights activists. This meant that progressives and liberals were labeled by Congress and the FBI as Communists and “fellow travelers.”

In 1947, deeply concerned about Communist involvement in the industry, conservative Hollywoodites took action. John Wayne and Walt Disney, who headed the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, invited the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to investigate the film industry for Communist influence, particularly on the part of unions and screenwriters.

Newly empowered Republicans taking over Congress were gearing up to repeal the New Deal, including Social Security. For years, members of Congress had criticized such subversive films as It’s a Wonderful Life, The Best Years of Our Lives, Crossfire, and Gentleman’s Agreement as being Communist inspired. HUAC Chair, J. Parnell Thomas, claimed that Hollywood movies were propaganda for Communism and the New Deal, thus pairing the two, and revealing that the Committee, ostensibly after Communists, was really after progressives and liberals. (Note: After some two decades of investigations, HUAC never found evidence of Communism in films.)

HUAC’s silent partner was the FBI, led by J. Edgar Hoover, who fed Congress names of suspected subversives, that is, people active in progressive activities in the CP (a legal political party), with the CP, or not. “Commie” would be stamped across anyone who believed in progressive causes.

HUAC’s and the FBI’s standard of just who was “subversive” was political. Those named would be brought before Congress for their political beliefs, a violation of the First Amendment. Those who refused to describe their political beliefs before Congress who invoked the First Amendment, were cited with contempt of Congress and, eventually, these men known as the Hollywood Ten, served time in jail (alongside the Chairman of HUAC). Subsequent persons called before HUAC would struggle with invoking the Fifth Amendment, which unfairly tagged them as guilty by the public.

At first, many in the movie industry fought back. A caravan of stars to Washington DC, led by Humphrey Bogart, intent on supporting the writers, directors, and actors HUAC had subpoenaed to defend themselves and their beliefs, crumbled at the first attack by Congress and scurried out of Washington. Bogart was pressured to admit he’d been a sap for the Communists in a major article in Photoplay. It was that or his career.

The movies were under attack.

HUAC’s hearings through the 1950s were essentially a mud sling, with names tossed out without evidence, accusations leaving a bleak image of an industry under siege. (“Expert” witnesses, such as character actor Adolphe Menjou, mentioned one actor who “acted like a Communist.” Walt Disney mistakenly claimed the League of Women Voters was a Communist organization.)

The once powerful movie studios could not object to governmental interference in their business. They might have, once. Not now. Knuckling under pressure, not wanting to appear unpatriotic and further damage their bottom lines, the studios proclaimed that no one suspected of subversion (and who invoked the First or Fifth Amendment as witnesses) would be hired or permitted to work in the industry. The FBI collected names and conducted intense surveillance, monitored houses, knocked on doors, questioned those inside, phoned them in the night, and searched through trash. Congress passed the McCarren Act, in which they set aside camps where, given a national emergency, “suspected subversives” would be rounded up and sent. Ex-FBI agents issued lists of names and then offered, for a fee, to clear them.

On the Small Screen

The blacklist spread its tentacles of fear throughout the 1950s and beyond, infecting movies, television, radio, and theater. Thousands lost their jobs. In movies and television, particularly, content changed. Movies that had engaged in social criticism vanished.

New kid in the living room, television, believed it needed to be on its best behavior and canceled shows where stars had the least bit of controversy. Somehow, shows with progressive creators, African American and Jewish performers, and women writers who had been climbing up the production ladder in the 1940s, were canceled. What did we get? Westerns with white men shooting from the hip littered the television screen as did crime dramas. If you want to know why television and movie content changed, why Leave It to Beaver and Donna Reed became the documentaries of the good old days, this is why. Producers and advertising sponsors were not going to risk controversy in any part of the country – east, west, north, or south. Which is why, although variety shows were planned with African American stars, they never happened for decades.

Former FBI agents compiled a book called Red Channels, with lists of names of suspected subversives, followed by organizations they supported, very few of them accurate, many of them misleading. But if your name was in the book, no television sponsor wanted you on their show.

And on the Big Screen

The movies had to compete with television and offer what television couldn’t. Big screens. Lush colors. Sex. And nothing un-American. And no pushy women in men’s jobs. If that was the character, they were ridiculed and pressured to accept women’s true calling, that of home and family. And if women weren’t aiming at marriage and children, they were fodder for fun as seen by the male gaze of the camera.

No, I haven’t forgotten about Dianna

She had played National Velvet, Anne Frank, and Juliet, and she was hoping for serious roles, like the ones her mother had played. She was still sixteen, though, and in 1960, movies and recordings discovered a powerful new teenage market. A new genre of movie, totally obsessed with sex that centered on male fantasy, became popular. Gidget Goes Hawaiian suffered emotional ups and downs about her steady, Moondoggie, and beach movies became a full-fledged genre with the all-American Disney Annette Funicello.

Even in Walt Disney’s Bon Voyage, the teen actress wore a bikini and boys gawked at her for several minutes of screen time. Going steady was made to be such a big deal that it was a major musical event in Bye Bye Birdie, and even in parody, it approved the intensity that girls thought of nothing else but catching a boy. More seriously, in Splendor in the Grass, the boy – high school star and handsomest boy in school – forced his girlfriend to her knees to worship him, and when the girl lost the boy, she had a nervous breakdown.

Dianna also had some concerns about the major films of the day.

She enjoyed Some Like It Hot (which did not get a Production Code seal and made tons of money, pretty much putting the Code out of business) but was uncomfortable with the use of Marilyn Monroe’s body as a joke – the train’s steam aiming at her rear end, the camera’s fascination with her legs, and the need for her to jiggle chest and rear end. The two men pretending to be women kept being annoyed by being pinched, but it didn’t occur to them that women would be annoyed by the same behavior from them.

Then there were the movies reprimanding women for working and enjoying careers. The Best of Everything advertised itself as being about “the ambitions and emotions of the girls who invade the glamorous world of the big city seeking success, love, money, and the best of everything – and who often settle for much less.” Three Coins in the Fountain told the story of three American women who took jobs in Rome, completely absorbed not by their jobs or being in Italy but snagging a husband. In Imitation of Life, when Lana Turner achieved her dream, success as an actress, John Gavin ordered her to stop, go home, and be a mother (because I love you!). Turner was in the wrong by doing what she wanted to do.

The film also criticized her mothering – or lack of it – seeming to ignore the fact that the “good” mother in the movie had a lousy kid. Psycho’s shower scene appalled Dianna (it fascinated her date) not only for the slashing of a naked woman in the shower but that the rationale for the blame was all dumped on “Mom.” Room at the Top and Anatomy of a Murder treated women as objects (and career women as objects of humor) and for some reason, Anatomy contained a long scene of a gratuitous joke about that humorous word, “panties.”

Where things were going is perhaps best exemplified by, of all things, a Julie Andrews film, The Americanization of Emily (1964), actually one fine film and a great role for Andrews between Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music. The director, Arthur Hiller, fought producers for a series of scenes to be “honest” – that is, with full nudity – not of Andrews’ character, who enjoyed a mature affair with Garner, but for three anonymous young women, each discovered in bed with James Coburn at different times and dubbed “the nameless broads 1,2, and 3,” (for the record, they were played by Janine Gray, Judy Carne, and Kathy Kersh).

At every interruption, Coburn and the “broad” would leap out of bed. Hiller wanted the actresses to be naked, but instead, they each grabbed something to cover their breasts. This wasn’t honest enough for Hiller. After all, they’d been having sex! But so had Coburn, and when he leaped out of bed, he was clad top to toe in striped pajamas. “Honesty” had to do with women’s bodies as one-off jokes. The male gaze of the camera had its own opinion about honesty. But that is the price of the male gaze – men using women’s bodies to think with and to entertain themselves with.

So Dianna, a skilled actor who loved her craft, faced a situation that would deteriorate in the next several years as men, freed from the constraints of the Production Code, controlled what the camera saw and how it saw it. Even as protected as Dianna was by her family’s power, her body was already being fetishized, and a director assaulted her.

Dianna learned, too, that there was another blacklist, one that prevented her talented Puerto Rican friend from auditioning for West Side Story, one that forced a brilliant jazz singer and an actress to make a living as servants in her home.

The treatment of actresses, particularly the young and vulnerable, continues to be a problem in the movie industry, which now inserts “nudity clauses” into contracts, their stipulations often broken by pressure on the sets. These elastic clauses were one of the triggers for the #MeToo movement.

It seems that Lianna/Dianna was telling me a story that leads right down to where we are and who we are.

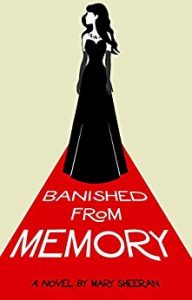

With Dianna’s encouragement, I wrote Banished From Memory.

Let’s not forget.

—

MARY SHEERAN has acted in plays, sung in operas, and created and performed in recitals and cabaret shows, all in New York City. She is the author of two novels, Who Have the Power (2006), an exploration of cultural conflict, feminism, and Native American history, and Quest of the Sleeping Princess (2012), set in the midst of George Balanchine’s ballets. She has written theater and dance reviews for show business trade publications and for the blog Life Upon the Sacred Stage. Mary lives in the Bronx, where in conjunction with earning a Master of Divinity degree from New York Theological Seminary, she can also be found giving sermons in Manhattan churches.

BANISHED FROM MEMORY

It’s 1960, and sixteen-year old Dianna Fletcher has been accustomed to the bright lights of Hollywood all her life, but now they are casting shadows on her family’s past and on her own future.

It’s 1960, and sixteen-year old Dianna Fletcher has been accustomed to the bright lights of Hollywood all her life, but now they are casting shadows on her family’s past and on her own future.

Dianna Fletcher is famous for her roles as a child actor and for her status as the daughter of two award-winning actors. But the bright lights of 1960’s Hollywood, to which she’s been accustomed for all sixteen years of her life, are casting shadows.

Dianna fears she is losing her talent and failing to live up to her family’s legacy. When she does land a part, she finds an unexpected enemy in brilliant actor and womanizer, Bill Royce, who not only attacks her confidence but holds a deep grudge against her family. Dianna comes to believe Bill’s resentment is related to her suspicion that her parents harbor a secret linked to the blacklist. But even as their friendship grows despite their misgivings about each other, Bill will not confess what he knows.

As Dianna struggles with her career in a rapidly changing industry, she urges Bill to share his dark past with her, only to discover secrets that could destroy her family’s prestige and power.

Banished From Memory highlights the conflicted relationships between two legacies of the blacklist, the sunset of classic Hollywood, the challenges and gifts of acting, and a determination on the part of one generation to exhume the truth of another’s. But at what cost?

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips