When a World Crisis Makes Your Backlist Historical Fiction Novel Suddenly Relevant Again: Is It Still Your Story to Tell?

When George Floyd’s televised murder and reaction, is startlingly similar to a historical incident depicted in your own two-year-old novel, how do you manage privilege and political correctness to revitalize interest in your story . . . and should you?

When George Floyd’s televised murder and reaction, is startlingly similar to a historical incident depicted in your own two-year-old novel, how do you manage privilege and political correctness to revitalize interest in your story . . . and should you?

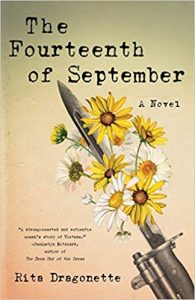

Since my protest days, I’ve been concerned about the hamster wheel of history, how we seem not to acknowledge the lessons of the past and the parallels to the present: a big reason I wrote my novel The Fourteenth of September, about campus Vietnam protests and the Kent State shootings, which happened fifty years ago on May 4.

May 30 found me in traffic in the middle of the first Chicago Black Lives Matter protest. Crowd control funneled us drivers into the epicenter of a demonstration that would hours later result in massive destruction, however right-intentioned and peacefully it began. It was familiar territory.

Trying to back out, I dodged protesters on foot and in cars draped with people hanging on doors open into the street pointing to signs saying silence was complicit, equating my escape attempts with cowardice. Back in the day, complicit had been my favorite protest word; rich and many-layered, it pretty much covers it all, intentional or otherwise. But how could I explain? They were looking at me the way I used to look at people who watched us from the sidewalks.

Suddenly, a cloud of protesters was climbing over us, darting between cars; for sure I’d inadvertently run over a foot or squash a knee. Someone would jump on my car, notice it was a Lexus, call me out—rendering my past activist cred invisible, irrelevant.

The crowd was mostly young, male, ready for action, one guy up on a concrete planter bouncing on his toes and shaking his hands like a fighter warming up, a look of glee on his face. A red-headed kid waved a sign and howled, gearing up. Not knowing what would happen, only that it was important, it would be exciting, they had to be part of it. I knew that look, I knew that bounce. I knew the night was gone.

After Kent State, when we’d also been aghast seeing our peers unbelievably murdered on television, we’d done the same. Universities across the country were set ablaze. We’d gathered with rage and energy, pacing the Student Union like lions. Something needed to happen to honor the fallen, to use the tragedy to finally change things. Factions formed for destruction—street action, they called it: Hit the man in his property. These are just things, versus lives. Others preached calm: end the draft (short term), stop the war in Vietnam (longer term).

In my car, I inched through the streetlights into a sea of blue helmets, uniforms with billy clubs in their belts. My stomach clenched, old reflexes back in action. They waved me through. I was safe, but felt the chill of guilt. In my day, fresh after the Chicago ’68 Democratic Convention, we’d learned to fear police. Some called them pigs. There had been change since then, it seemed, until lately, until George Floyd. As I passed the advancing helmets, I feared it would be ugly.

The planned response to Kent State at my university had been to be peaceful. But being powerless for years and draft-age targets, for some the rage was hard to contain. The chilling sound of the first broken window signaled all bets were off. Hundreds of students streamed into town where they broke every window, pulled up landscaping, turned over benches, alienating the townies. Others went to the dorms, destroying the glass front of the utility building, plunging the campus into darkness, setting a cop car on fire, alienating the university.

There were arrests. The National Guard arrived with their rifles. They were the Kent State killers. Would they shoot us too? It was terrifying. It was out of control. It spread across the country. Kent State ended up being a turning point against the war—but it took a very long time to recapture the message. This is an important part of the story I tell in my novel, one I wanted to jump out of the car and tell the protesters.

I’m gratified: this time the BLM message seems to be resonating despite the violence. Yet every new spike on either side continues to speak louder than the sound of progress. I get that powerlessness leads to rage. If we’re in the streets it means that the regular channels didn’t work.

Am I allowed to talk about that?

I’m encouraged the BLM movement has both promise and, it appears, legs. It gives me faith that we can still change the world, a quest my generation couldn’t pull off. But I am enraged that it took a violent death flashed in our faces to get us here, after a series of videoed violence, way back to Kent State. I feel like a spectator watching gladiators duke it out. Must history be like this, a bloody hamster cage?

There is one thing I know. The minute the first piece of glass breaks, that sound is all anyone hears.

Can I say that?

I think I’ll settle on: I have a novel that depicts a small sliver of this grand story which could fuel a phrase in the overall conversation.

And the more voices we hear from, the more likely the path of progress will be straight forward, swift and permanent, and we can finally retire the repetitive hamster wheel.

..

Rita Dragonette is a writer who, after spending nearly thirty years telling the stories of others as an award-winning public relations executive, has returned to her original creative path. The Fourteenth of September, her debut novel from She Writes Press, is based upon her personal experiences on campus during the Vietnam War. It has received the Beverly Hills Book Award for Women’s Fiction (2018), National Indie Excellence Awards for New Fiction (finalist 2019) and Best Cover Design (finalist 2019), American Book Fest Fiction Awards for Literary Fiction (finalist 2018) and Best Cover Design (finalist 2018) and the Hollywood Book Festival (honorable mention 2018, general fiction).

She is currently at work on three other books: an homage to The Sun Also Rises about expats chasing their last dream in San Miguel de Allende, a World War II novel based upon her interest in the impact of war on and through women, and a memoir in essays. She lives and writes in Chicago, where she also hosts literary salons to showcase authors and their new books to avid readers.

About The Fourteenth Of September

On September 14, 1969, Private First Class Judy Talton celebrates her nineteenth birthday by secretly joining the campus anti-Vietnam War movement. In doing so, she jeopardizes both the army scholarship that will secure her future and her relationship with her military family. But Judy’s doubts have escalated with the travesties of the war. Who is she if she stays in the army? What is she if she leaves?

On September 14, 1969, Private First Class Judy Talton celebrates her nineteenth birthday by secretly joining the campus anti-Vietnam War movement. In doing so, she jeopardizes both the army scholarship that will secure her future and her relationship with her military family. But Judy’s doubts have escalated with the travesties of the war. Who is she if she stays in the army? What is she if she leaves?

When the first date pulled in the Draft Lottery turns up as her birthday, she realizes that if she were a man, she’d have been Number One―off to Vietnam with an under-fire life expectancy of six seconds. The stakes become clear, propelling her toward a life-altering choice as fateful as that of any draftee.

The Fourteenth of September portrays a pivotal time at the peak of the Vietnam War through the rare perspective of a young woman, tracing her path of self-discovery and a “Coming of Conscience.” Judy’s story speaks to the poignant clash of young adulthood, early feminism, and war, offering an ageless inquiry into the domestic politics of protest when the world stops making sense.

Category: On Writing

Wow! What a book. I grew up in the Kent State area and was a high school sophomore on May 4. Such a long view of deaths, assassinations, terror, mixed in with a happy life. You really made me think this morning! Thanks for sharing your book.