MY TWICE-TOLD TALE: WHY I WROTE GOOD NEIGHBORS, BAD TIMES REVISITED

By Mimi Schwartz

By Mimi Schwartz

When I was growing up Jewish in Queens, New York after World War II, I was taught that America was a Melting Pot. And if I jumped right in, I could be like everyone else—even if my parents, who were refugees from Hitler’s Germany, said ‘moder’ and ‘fader’ instead of ‘mother’ and ‘father’ and ate liverwurst sandwiches, never peanut butter and jelly. If my friends didn’t care, that’s what mattered.

What didn’t matter, I thought back then, were stories my father told about the little German village where he was born. That was Old World. I was New World, born In New York City three years after they resettled first in Jackson Heights, and then Forest Hills. So whenever my Dad began telling me about the Jews and Christians of Rexingen, I tuned out.

In Rexingen, before the Nazis, we got along, he’d say with nostalgia about his boyhood before Hitler. In Rexingen, children knew how to behave! (That was after we fought over the bathroom and the “good” window in the car.) He didn’t talk much about the horrendous last years in Germany before he fled in 1936, but most Jewish refugees didn’t. Which was fine with me, who so wanted to be 100% American, past-free.

As an adult, of course I read about the Holocaust, but that history never seemed connected personally to me. That is, until my forties, when on a trip to Israel, I saw a charred Torah in the Memorial Room of Shavei Zion, a moshav north of Haifa that was founded by a group of Rexingen Jews that knew my father as a boy.

The old man, showing me around, said the Torah had been rescued on Kristallnacht—not by the Jews, but by their Christian neighbors and sent it to them here. Having grown up on movies of evil Germans, Nazis all, I was skeptical, but then my father’s words In Rexingen we all got along! came back to me. Maybe some of those same people had risked saving the Torah, trying to be decent even in Nazi times.

I wanted to ask my Dad about it—now all his stories seemed interesting—but he’d died twenty years earlier. Like many of us, I waited too long. When I asked my mother, she said, “I came from Stuttgart, not from little Rexingen.” End of story. She too wanted the past behind her.

In Washington Heights, at an annual get-together of Rexingen Jews who restarted their lives here, I met two dozen people who did want to talk about the lives they once had. They told me how they hated Germany for betraying them, but often not their next-door neighbors. “Many were “decent people, but what could they do?” That surprised me; I expected more venom—and began to wonder about decency then. And also What would I have done for neighbors under threat? And what would I do now?

I decided to go to the village and meet their former neighbors, those remembered fondly. I found them, none brave enough to risk hiding anyone, not in a village of 1,200, so no one stopped 89 Jews (out of 350) from being deported to concentration camps. What they did, aside from saving a charred Torah were small acts: like bringing soup at night to the old widow who couldn’t get a visa, sharing a ration card, cutting Jewish hair despite the Nazi sign forbidding it.

Mostly small stories, but ones that made me feel: this I could do. If enough people had done them, I came to think more and more, the Nazi politics of hate might have failed. But there were not enough. As one woman, who grew up as a half-Jewish child in the village during the Third Reich, told me: “There were ten, maybe twelve, families, without which we wouldn’t have survived…There were maybe another ten who hated us, the Nazis of the village. The rest didn’t care, but they left us alone.”

I wrote the story of meeting these villagers who once were neighbors in Good Neighbors, Bad Times, Echoes of My Father’s German Village—and thought I was done, ready to move on, away from the Third Reich and back to New Jersey life. Which I did for ten years, until a letter arrived from a man in South Australia.

His name is Max, age 88, and he wanted to thank me and to say, “Your father was right…We all got along!” Max, it turns out, had grown up five houses from where my father’s family lived for generations. But they never met because his Catholic family moved in a few months after my uncle Julius sold the family house in 1937 and fled Germany.

I answered Max and he shared his private memoir, written twenty years earlier, about his boyhood in Nazi times. I was drawn to its unguarded honesty, his boyhood perspective that was all new to me. I read of Max’s first Hitler parade (age five) and his being a leader of his Hitler youth group (age ten) and the village boy chosen to attend one of Hitler’s elite boarding schools (age twelve). Yet Max was also the child who worried about the little Jewish girls he knew, fleeing to England:

Further down on Ihlingerweg there lived a couple of girls about my age and…I felt sorry for them as I knew they couldn’t speak English, and I said to Mum “but they can’t talk to anybody.” Mum said they can’t speak to anyone here either.

Previously, when my story focused on decency in the village, I’d avoided Nazi families, sure that I knew what they’d say and do. Had I clumped everyone too simply into two groups, good or bad neighbor, leaving little room for the gray of complexity? If so, where was Max’s family?

True, his father joined the SA (storm troopers) in 1926, but he also quit ten years later, unhappy with the rabid anti-Semitism towards the Jews he knew. True, Max sneaked into the burnt synagogue after Kristallnacht with his friends and took a souvenir, (he was eight), but his mother made him bring it right back. And he did help three old Jewish sisters light their fire every Shabbat. So on what moral scale do you weigh a child in the Third Reich? Or, for that matter, his unknown family?

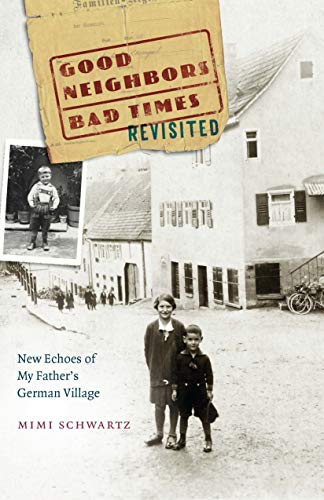

While reading Max’s memoir, I heard his stories talking to mine, as if out of different windows of history. I imagined weaving excerpts from his memoir into mine and so began a new story, Good Neighbors, Bad Times Revisited: New Echoes of My Father’s German Village.

Over the next year, our conversation across oceans and time continued: I asked Max tough follow-up questions—Did you have any Jewish friends that you dropped? Why did you go to this boarding school?—and he answered. And he asked me questions, all through his son Mäxle, who was our intermediary, sending our emails back and forth. We also shared photographs and facts that we researched, and with each new effort to cooperate, a trust began to grow—and that became part of the new story.

Eventually I met the whole family on Zoom—Max, his wife, and three children. His son Bernhard said how grateful he was that his Dad had written his memories down. It was a gift. To me as well, I said, because my father’s stories had stayed in the air, barely heard by a girl who didn’t listen hard enough.

There was another gift, which we all accepted gratefully: the chance to connect positively with those who had seemed like “the Other.” That did not mean forgetting the past—or pretending, as in the Melting Pot myth, that we are all same. We just shared our stories and helped each other fill in gaps of village history. Most important, we risked being honest and risked listening, as we slowly moved forward across a bridge of cooperation into a place where empathy replaced enemy.

So when President Biden’s in his Inaugural Address said: “We can see each other not as adversaries, but as neighbors,” I’ll vouch for that possibility. It’s real and we so need it now.

—

Mimi Schwartz is an award-winning author, educator, and public speaker whose books include When History Is Personal (2018); Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed (2002); and the ever-popular Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, co-authored with Sondra Perl (2006).

Mimi Schwartz is an award-winning author, educator, and public speaker whose books include When History Is Personal (2018); Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed (2002); and the ever-popular Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, co-authored with Sondra Perl (2006).Category: On Writing