Writer in Prison

It was my first day in prison and I had a big to-do list:

It was my first day in prison and I had a big to-do list:

- Put your belt kit and key pouch on.

- Empty your pockets and purse of money, ID, anything that might hold an address or personal details, because information can be used against you

- Bring nothing inside that can be used as a weapon: no cutlery, no safety scissors

- Try not to think, with your bag full of pens, about how they could be used as weapons, both physically and philosophically.

On my first day at a young offender prison, I turned up early, green as grass. I also bought in a metal teaspoon, which was quickly taken from me as contraband. I didn’t know how to hook the massive ring of chunky iron keys to my belt, and once they were on, they felt heavy with responsibility.

I couldn’t find my way across the strangely beautiful prison grounds, a former borstal with old brick Victorian blocks, where young offenders in bright green jumpsuits planted pansies and primroses, already in bloom. I knew these offenders might be in for any number of violent offences, but I felt nothing but love for them and their circumstances, as well as the officers who were there to keep them safe. I didn’t know what that surge of love was when I came through the prison’ big wooden gate, but I felt my heart burst open then and every time I entered for the next four years, as their new Writer-in-Residence.

I was given the job by Writers in Prison and the Arts Council, funding for both of which has been cut, sadly. The premise was that a writer could support the prison, both officers and offenders, in a different way to other key staff. I was to support prison policy, but not to be of the prison. I was to support the offenders’ views and rights, while helping them to understand their responsibilities as part of a community. I was not a chaplain, counsellor, nurse or teacher – they already had plenty of those. I was there to simply be a writer, to encourage communication, inspiration, creativity and literacy. It was an enormous privilege to be there – and I learned far more than I ever “taught”.

I ran a small magazine team from the library, where I commissioned articles, proofed and cajoled, and oversaw the design and layout. The highlight of our month was delivering the magazines from wing to wing with a metal cart, as young men banged on their doors from the inside, saying, “Miss, Miss, get me on your team. I’ve got some bare lyrics!” I ran competitions on the wings, dragging in a sound system to let men freestyle to beats I’d bring in.

These led to filmed rounds which were “broadcast” in their cells on lonely days like Christmas and Easter, for the men to vote by ballot for the winner of “Rap Idol” or “Lord of the Wings.” Often, I stood outside doors in the segregation unit, bearing witness to extraordinary pain and suffering with nothing to offer but a paper and pen. But, mostly, there was writing, sitting in quiet groups with young men who had a desperate need to connect, to commit their thoughts to paper, whether they had the ability or not. Illiteracy is a huge problem in prison, as is despondency.

It isn’t easy to love a prison. It is crowded and noisy, filled with shouting and the clang of metal doors. The wings smell, a potent mix of bleach and drains and fear that I can still remember. Occasionally, it is frightening, when the temperature soars, when the wings feel jumpy, when the threat of revolt or riot runs high. For four years, I was one constant in an ever-changing population of governors, staff, officers, and offenders.

The prison itself changed, with new wings added, buildings repurposed, and the population increasing, year by year. Over four years, I hope I challenged them. Together, we read poems and lyrics that were new to them. They loved Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Oliver, whose opening line to “Wild Geese” always made them listen: “You do not have to be good”.

The prison itself changed, with new wings added, buildings repurposed, and the population increasing, year by year. Over four years, I hope I challenged them. Together, we read poems and lyrics that were new to them. They loved Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Oliver, whose opening line to “Wild Geese” always made them listen: “You do not have to be good”.

They were less keen on Joni Mitchell and Sylvia Plath, but they tried them, because their respect for poets and lyricists is strong. For me, they tried to freestyle to new rhythms, particularly jazz, instead of their usual loops and beats. Their take on Miles Davis, “spitting” to “So What?”, will long stay with me.

They certainly challenged me. They could be rude and lazy, sleepy or high. They would refuse to write or even try, because their fear of failing, again, was all consuming. They challenged my assumptions about young men and crime, as well as my sense of self.

And they challenged my writing. When I arrived, I was a playwright, but they didn’t want to write plays, could find no relevance or interest there. Because I could not change a prison, I had to change myself, and so I had to change my writing. I began to write the poetry and short fiction I asked them to write, and I realised that I could write differently.

It was, in prison, that I began the first tentative steps toward writing my first novel, which was published not long after I left. By then, my sentence was longer than any young man I’d worked with. I’d already seen men leave and come straight back, bashful and bemused, saying, “Sorry, Miss. I did try to stay out. I did try.” When I left, I promised myself the same thing. So far, I’ve managed it. But I do miss it.

—

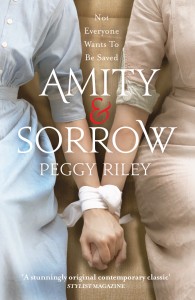

Peggy Riley is a writer and playwright. Amity & Sorrow was published in the UK & Commonwealth with Headline/Tinder Press , Little, Brown in the US, and in translation in the Netherlands with Orlando, France with Cites de la Presses, and in Italy, Sonzogno. She has been a festival producer, a bookseller, and writer-in-residence at a young offender prison. Originally from LA, Peggy now lives in Kent.

Find out more about her on her website http://peggyriley.com/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (6)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- Writer in Prison | WordHarbour | September 16, 2015

- Writing in Residence | Peggy Riley | September 15, 2015

What a superbly written article. I loved your sentence “By then, my sentence was longer than any young man I’d worked with.” Though I’ve never seen the inside of a jail, as a writer propelled by that fire in the belly, I can relate.

Inspiring. Thanks for sharing

A great post, Peggy, Very interesting and poignant. I’m sure your impact is still felt by those young people and that they will remember your skills and gentle presence for all of their days. I’ve shared it on the YM Facebook page. Marnie

Wonderful article. The journey has many turnings. Must have been very humbling and full of gratitude..