Writing About Social Injustice, With Monsters

Blending fact with fiction is complicated enough. But when the fact is a well-known tale of social injustice that happened in a place that would later become home to a beloved baseball team, let’s just say I approached the project like a prickly pear cactus.

I’m talking about Chavez Ravine, home of the Los Angeles Dodgers. But before the stadium, it was a rural, hilly area home to mostly Mexican American families, including my mother, uncles, aunts, and cousins.

The city sent eviction notices in 1950, informing the residents of its plan to build low-income public housing.

Like many others, my family owned their homes, so had no desire to leave them to rent apartments in a sprawling housing project.

Some people resisted. They organized and showed up at public meetings, carrying protest signs.

My family did not. They took the payout and left. Not because they were undocumented and had no recourse. They were American citizens. They just weren’t the type to push back against the powerful institutions pushing them out. City officials eventually abandoned their plan for the housing project. Years later, the city sold the land to the owner of the Dodgers.

Several excellent non-fiction books detail the struggle between city and citizens.

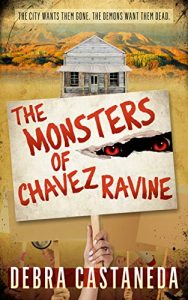

While my story, The Monsters of Chavez Ravine, is an urban fantasy, it’s rooted in reality.

I decided to set the story in 1952, after most of the residents had left, leaving only the most stubborn holdouts spread out over the three eerily quiet neighborhoods of Palo Verde, Bishop and La Loma.

But as I thought of the place and the people who occupied it, I got to thinking about what I did not want to do.

I did not want to focus on victimhood or portray the characters as weak and powerless. The communities had their share of happy, productive people who had jobs and paid taxes, so they deserved their dignity even though, in the end, they were forced to leave.

I could not bring myself to portray the residents as poverty-stricken barrio dwellers.

They’d already endured enough insults, hearing their home referred to as a “crime ridden health trap,” an area “blighted by substandard housing” and themselves as, “immigrant slum dwellers.”

Sure, many of the people were poor. Some were recent arrivals from Mexico. Many trekked down the hill into the city for low-paying work, digging ditches or working in the rail yards.

But the story I imagined was not about the daily indignities of poverty, of mothers sewing underwear for their daughters from flour sacks or kids going to school barefoot.

For one hundred and seventy pages, I did not once use the word, “barrio.” Not even when the fictitious politicians hurled insults at the residents during one particularly nasty public meeting.

Yet almost all the characters are Mexican American. And while the overarching theme is that of a marginalized community dealing with a great social injustice, I thought it important to give them both dignity and enough agency to fight against monsters both political and literal.

I gave the characters ordinary jobs: small business owners, a Spanish translator, a seamstress for a designer (like my grandmother!). They owned homes, which they fought to keep. Mostly, I strived to make them relatable, yet as unique and quirky as you’d find in any community.

There’s a convict turned reputable citizen named Ripper, plus a half-dozen young men loosely based on some boys I knew growing up east of Los Angeles.

And when the monsters show up, I stick a gun in my heroine’s hand and have her rescue the handsome community organizer, more skilled at fighting the city than the demons.

The idea of a young woman defying norms in early 1950s America didn’t come out of nowhere. My great Aunt Vita was a force to be reckoned with back in the day. The young widow ran a successful restaurant on her own while raising her son. She wouldn’t have had much patience with any boogeymen showing up at her door.

And speaking of the boogeyman, he’s called El Cucuy in Mexican American households, so I used the Spanish word in the story.

In fact, I decided to include a decent sprinkling of Spanish words into the novella without italicization, but with context, so readers could easily figure out their meaning. Somehow, italicizing Spanish words said by bilingual characters threw off the pacing and, at some point, seemed silly. After all, these words were part of a blended language being spoken by Americans, so they weren’t really foreign. I included a short glossary at the end.

As a Latina author, I feel a responsibility to not only entertain, but to inform readers who might not have heard about what happened to the old neighborhoods of Chavez Ravine.

Even the name Chavez Ravine is complicated. That’s what people call it now. For the sake of ease and clarity, that’s what I decided to call it, too. But before the bulldozers arrived, my family would simply say they were from Palo Verde.

In the big scheme of such a book, this kind of detail can seem rather trivial. But it’s exactly what can cause a reader who knows about the history of the place, or has family from there, to question the authenticity of the story or the author’s right to tell it.

In the end, I can only hope that I did right by the people who once called Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop home.

https://twitter.com/CastanedaWrites

The Monsters of Chavez Ravine

Before Dodger Stadium, dark forces terrorized Chavez Ravine

Before Dodger Stadium, dark forces terrorized Chavez Ravine

Los Angeles, 1952. When her father is attacked under mysterious circumstances, 22-year-old Trini Duran must return home to Chavez Ravine, a neighborhood mostly abandoned after the government sent letters to residents demanding that they leave.

Only two hundred stubborn holdouts remain.

While the Mexican American community fights to save their homes, they face a new threat that is even harder to combat than the politicians who want them gone.

Trini discovers the city and the supernatural have joined forces against her old neighborhood—monstrous creatures emerge at night, terrorizing the holdouts.

Trini, a handsome community organizer, a healer with dubious skills and a ragtag group of fighters, take up arms against the elusive enemy.

But to stop the demon invasion, Trini must decide how far she’s willing to go to save the place she once left behind.

Buy Here

Category: On Writing

Buenos Dias Debra,

I just finished reading your description of how you wrote your most recent book.

Truly powerful words.Hit me like an explosion

That someone can actually feel what it meant to live in Palo Verde.

I look forward to hearing from you. Enjoy your weekend and stay safe.

Sincerely

Rachel C.Cantu