Writing about War and the Homefront by Anne Vines

by Anne Vines

In my early days of writing fiction, I did not set out to write about war. But perhaps because I was born a few years after World War Two ended, it was a fascination in my reading and film watching, so I should have expected it to well up sometime into my writing.

It did so one afternoon as I walked along Collins Street, Melbourne’s poshest street full of haute couture shops and theatres, restaurants, up-market hotels and private clubs. I glanced up at the Regent Theatre and stopped for a moment. The Regent is a live musical and ballet venue now, but for decades was a cinema. In World War Two, it was a leading movie house where American servicemen and Melburnians watched the newsreels and the latest feature films. There is a long stone staircase up to the lobby which is full of ornate gilded carving. I imagined Melbourne girls seeing Americans there for the first time. I wrote a short story.

Years later when I had more time, that story kept playing in my mind, and a longer story grew.

A lot of my writing is spontaneous and seems to come out of nowhere – but of course it comes from thought, reading, conversation and experience. Like a lot of writers, I am only half aware of what I am creating – at first. As I reach the end of a first draft, I am aware of what I want to say, what I want my readers to see. The themes of aggression, inequality and poverty were what I wanted to tackle. And the extremes of hate and love, power and generosity. Writing about war gives these themes great scope.

I wanted two contrasting main characters. One came from a secure, stable, protected, loving family and a privileged, affluent place in society. She had everything – except equality and independent thinking. I would show the war changing her. The other character was poor and unprotected – but he is also a free spirit unfettered by social rules and thinking. I wanted to write about how young men recovered – if they could – from abusive childhoods. How did they forge relationships with women that were honest, deep and lasting? How could war make this easier and also harder?

My novel’s world and style would not be straight realism but would fit into the era and stay close to the facts. Referring to the music and movies of the period would strengthen the creation of the atmosphere. As some historical fiction has done, I would view the era I was creating from my time, my values, with a story arc that interrogates the wartime and home front.

I was always fairly sure that I would concentrate on the home front. I would keep battle scenes to a minimum. I wrote some, then cut them. Other writers, almost all male, have given us the detail. I was interested in how my pilot remembered the fighting but did not speak about it. I focussed on how the home front changed him.

While I wrote drafts and cut many words, I kept researching. My knowledge of Melbourne in the 1940s began when I was a child, with snippets from my parents, uncles and aunts.

When I was an adult, my Auntie Pattie told more complex stories. She had been a teenager during the war. Her picture of the Americans was largely positive; she recalled group outings and home dinners offered to shy boys. She recalled how resentful some Melbourne men were of the Americans, and how negatively they judged some women who went out with Yanks.

She gave me a clearer idea of the atmosphere and how it changed by the end of the war. She had completed a most successful career in the Navy, retiring as a Commander. It was wonderful to have her support and she hoped the book would be published. Sadly, she died before I managed to get it into print, but her spirit lives on in some of the book’s details as well as in my acknowledgements.

Some years ago, in my writing group, I was lucky enough to meet older women who had lived through the war, affluent, educated women, writers who recreated that time and commented on it. One had met an American marine officer in the Botanic Gardens and had married him. It was such serendipity that I happened to hear their stories.

I have not used anyone’s real life experiences in Flight. The characters and their stories are imagined.

There has not been much fiction written about women’s experience in Melbourne during World War Two. Toni Jordan’s Nine Days gives a moving, vivid snapshot of a part of Melbourne and some women’s lives. In Flight, I have focused on several women characters from different milieux, who have very contrasting times in Melbourne.

Researching a past era is so much easier now than when I began this novel years ago. A great deal of film footage is available on library sites and YouTube. It is wonderful to watch real people from the past and imagine your characters being right there.

Writing about my own city and its past led me to look closely at more of Melbourne than I had noticed before. When I found pictures or film of those places back then, I enjoyed seeing the history of my town up so close.

***

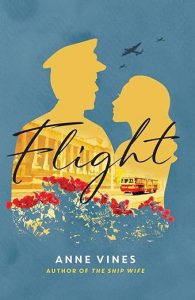

Anne Vines’ first novel, The Ship Wife was published in 2023. It is historical fiction based on a true story. Anne won the Boroondara Prize in 2014 and the Keith Carroll Award in 2020. Her short stories are published in Award Winning Australian Writing 2015 and other anthologies. She was commended in the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an Unpublished Manuscsript in 2008 and the Varuna Harper-Collins Award in 2007. She was shortlisted in the Alan Marshall Short Story Award, The Age Short Story Award and the Wasafiri International New Writing Prize. Anne’s second novel, Flight, published in May 2025, is historical fiction/historical romance, written from the viewpoints of an American pilot and a Melbourne woman in 1942.

Flight by Anne Vines

Flight is an historical romance set in World War II by Melbourne author Anne Vines.

Flight is an historical romance set in World War II by Melbourne author Anne Vines.

In 1942, American servicemen appear on the streets of wartime Melbourne. Though Australians enjoy American films and music, some Melburnians find it confronting to meet real Americans, even though the Yanks have come to protect Australia from a feared Japanese invasion.

American flyer Peter can barely remember a time when he didn’t need to fight. His life is still a flicker away from nightmare; he only feels at home in a fighter plane. When he comes to Melbourne, the girl he wants is Faye, but he’s not in the race. He’ll never be the marrying kind. Yet Faye is the first woman he’s going to miss, more than his other friend, Tivoli dancer, Iris.

Faye finds herself engaged to Melbourne’s most eligible man. But he never looks at her as if there is no one else in the world. Then Peter gives her just that look. She must decide what she wants, and learn how to fight for it. Snobs and moralists in Melbourne say that nice girls don’t go out with Yanks. Faye and Iris face new choices and dangers in a time of change. And then the war intervenes, with life-changing consequences for Peter and Faye.

Anne’s first novel with Glass House Books was The Ship Wife.

Published by Glass House Books, IP (Interactive Publications Pty Ltd)

Category: On Writing