Writing and Researching The Empress and the English Doctor: How Catherine the Great defied a deadly virus

I’m the writer who took the sex out of the story of Catherine the Great. Actually, that’s not strictly true: I may be British, but I’m not that prim. What I really wanted to do when writing my book The Empress and the English Doctor is ditch the false sexual smears trotted out (ha!) for over two centuries, and replace them with a barely known true story showing how Catherine II of Russia used her body to promote science.

I’m the writer who took the sex out of the story of Catherine the Great. Actually, that’s not strictly true: I may be British, but I’m not that prim. What I really wanted to do when writing my book The Empress and the English Doctor is ditch the false sexual smears trotted out (ha!) for over two centuries, and replace them with a barely known true story showing how Catherine II of Russia used her body to promote science.

Even back in my school classroom, when I first saw a satirical cartoon showing the Empress striding across a map of Europe as rival (all male) monarchs looked sneeringly up her skirts, I felt I wanted to analyse this woman as a man would be judged. Several decades later, this time in a schoolyard collecting one of my kids, I met a fellow mother with an extraordinary connection to Catherine, and knew I had found the tale I wanted to tell.

The woman I chatted to turned out to be a descendant of an 18th century English Quaker physician called Thomas Dimsdale, a renowned expert in smallpox inoculation. That procedure, the forerunner of vaccination, involved giving healthy individuals a tiny dose of live smallpox virus via a scratch on the arm, inducing a mild case of the killer disease and conferring immunity for life. It had been in use for centuries in China, elsewhere in Asia and parts of Africa, but in Europe only Britain had adopted the technique with enthusiasm. In the spring of 1768, as the virus threatened her court at St Petersburg, Catherine ordered her ambassador to London to recruit a suitable doctor to inoculate her and her son Paul, and 56-year-old Dr Dimsdale agreed (reluctantly) to make the 1,700-mile journey to Russia.

My book tells the story of the encounter between the charismatic reformist empress and the earnest, quietly-spoken medic, both of whom risked their lives in the name of a cutting-edge scientific procedure. Inoculation was safe, but far from foolproof, and Catherine’s courageous decision defied widespread superstition in Russia. Had things gone wrong, Dimsdale would have been unlikely to escape with his life (although the Empress had moored a yacht in the Gulf of Finland ready to sail him to safety if he could reach it).

The rollercoaster events of Catherine’s preparation, treatment and recuperation are thrilling. But even more fascinating to me were her actions afterwards. The moment she and her son had recovered, she launched a tireless campaign to use her own example to promote inoculation across her empire. Orthodox masses, celebratory poetry and an allegorical ballet titled ‘Prejudice Defeated’ all proclaimed the Empress’s triumph, as Catherine urged her subjects to follow her lead. She even announced an annual public holiday in celebration of her inoculation, judging that parties and persuasion would overcome resistance among her subjects more effectively than autocratic decree. She set a fashion among the elite, commissioned inoculation hospitals and even two decades later was still instructing her officials to have their local populations undergo the procedure.

Catherine’s campaign, as I saw it, was the perfect truthful counterpoint to the myths and sexual slurs that have dogged her reputation. She had indeed used her body in power, but as a kind of one-woman scientific trial, and then as a means of defining herself as a forward-looking, enlightened monarch bringing the latest lifesaving technology to Russia. It was the perfect personal-political act.

Finding a story, of course, is only the beginning of an author’s journey. For me, that obsession stayed stored in my head for seven years as I freelanced as a journalist, worked in communications at Cambridge University and carried on bringing up my three kids. When I had time, often late in the evening, I would scour digital archives or academic articles, hunting down more about the meeting between the Empress and the English doctor. Finally, in 2019, I approached the Dimsdale family, and asked if they would make their extraordinary collection of papers connected to Thomas and Catherine available to me. With generosity and trust I can never repay, they said yes, and I was able to create a book proposal to present to an agent in November 2019. Just weeks before the world would be plunged into chaos by a new virus, I pitched a story about an eradicated disease, arguing my tale of female leadership, risk, trust, bodies and the clash of reason and superstition had enough resonance to interest modern readers.

My wonderful agent Cathryn Summerhayes at Curtis Brown took a chance on me. Not only that, she sold the book, which was picked up by Oneworld in March 2020. By then, however, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was ripping across the globe, and – just a few days before I signed my contract – the United Kingdom went into lockdown. Archives and libraries closed their doors along with pubs and restaurants, and my promise to deliver my book in just over a year looked distinctly ambitious.

In the end, reader, I managed it. Central to my research were the Dimsdale family papers, including Thomas’s handwritten medical notes on Catherine’s health both before and after her inoculation and letters between the two reflecting a lifetime’s friendship after the event. There was no chance of seeing the real documents, but photographs I could expand on screen served me well. For a sense of connection to my subjects, I relied on research visits I had already made: one to St Petersburg, where I had trodden the paths of Tsarskoe Selo, the palatial estate where the Empress recuperated, and others to Bengeo, where Thomas Dimsdale’s house and small inoculation hospital are still standing, and Epping, the town where he was born in 1712.

Stuck like so many in front of my screen, I wrung everything I could from digital archives, including Russian state repositories which – fortunately for me – include the correspondence of 18th century British ambassadors and their ministers in London. Even online, I could feel the rising anxiety as both sides exchanged encrypted despatches detailing the concern of King George III over the risks of the inoculation. What if a British subject accidentally killed the Empress of Russia, then an allied power? Medical archives, such as the collections of the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal Society, proved a treasure trove of treatises and reports showing how a strange new procedure no one understood was somehow protecting against the biggest killer of the age. The documents also revealed that no sooner had inoculation come to England than opposition to it had begun. A Yorkshire doctor wrote in 1721 that his efforts to inoculate were being opposed by people spreading ‘false report’ – fake news – and the earliest reference to the word ‘anti-inoculators’ I found was all of three centuries ago in 1722.

As I tapped away at my keyboard and the BBC broadcast its tragic daily toll of Covid deaths, the resonances between my book and the present were clear. Accounts of smallpox epidemics in my own home county, Essex, reported markets and schools closing and towns facing economic crises as visitors stayed away. Letters lamenting the loss of family members to smallpox laid bare the grief and sorrow also suffered by so many during the new pandemic. Debates over vaccines – and the varying approaches of political leaders – echoed the inoculation arguments of 250 years before.

I only refer to Covid at the beginning and end of my book: the events of October 1768 and their consequences stand in their own right. But no writer can look back on any event in history from anything but the viewing platform of the present. What we see is shaped by who we are as individuals, and by our times – anything else would be merely a chronicle. I brought to my book my fury at age-old slights against a complex and remarkable Empress, and set out with a mission to expand a footnote in her history into a full story of courage, statecraft and foresight. Events around me as I wrote strengthened my focus on the collective experience of epidemic disease, and on the complex human response to scientific innovation and to risk.

Readers can judge for themselves whether that particular alchemy worked. But I hope that, at least, I’ve shone a brighter light on this episode in Catherine II’s long reign, and left some of the lies in the dark where they belong.

—

Lucy Ward is a writer and former journalist for the Guardian and Independent. As a Westminster Lobby correspondent, she campaigned for greater women’s representation. From 2010–12, she lived with her family in Moscow, renewing her interest in Russian history. After growing up in Manchester, she studied Early and Middle English at Balliol College, Oxford. She now lives in Essex.

Find out more about Lucy on her website https://www.lucyward.uk

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/lucymirandaward

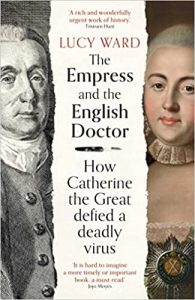

The Empress and the English Doctor: How Catherine the Great defied a deadly virus

The astonishing true story of how Catherine the Great joined forces with a Quaker doctor from Essex to spearhead one of the first global public health campaigns.

The astonishing true story of how Catherine the Great joined forces with a Quaker doctor from Essex to spearhead one of the first global public health campaigns.

A TIMES BEST BOOK OF 2022 SO FAR

Shortlisted for the Pushkin House Book Prize 2022

‘Sparkling history…with a fairytale atmosphere of sleigh rides, royal palaces and heroic risk-taking’ The Times

A killer virus…an all-powerful Empress…an encounter cloaked in secrecy…the astonishing true story.

Within living memory, smallpox was a dreaded disease. Over human history it has killed untold millions. Back in the eighteenth century, as epidemics swept Europe, the first rumours emerged of an effective treatment: a mysterious method called inoculation.

But a key problem remained: convincing people to accept the preventative remedy, the forerunner of vaccination. Arguments raged over risks and benefits, and public resistance ran high. As smallpox ravaged her empire and threatened her court, Catherine the Great took the momentous decision to summon the Quaker physician Thomas Dimsdale to St Petersburg to carry out a secret mission that would transform both their lives. Lucy Ward expertly unveils the extraordinary story of Enlightenment ideals, female leadership and the fight to promote science over superstition.

‘A rich and wonderfully urgent work of history’ Tristram Hunt

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing