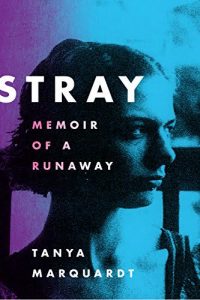

The Idea of North: Writing and Recovery By Tanya Marquardt

I wrote the first draft of my book Stray: Memoir of a Runaway drunk. Like blind, staggering drunk.

I wrote the first draft of my book Stray: Memoir of a Runaway drunk. Like blind, staggering drunk.

In 2010 that’s what I did best. I had gotten into a prestigious MFA Program, moved from Canada to New York after my mother co-signed a loan from the bank, and had two years to spend my days writing. Which I did do. It’s just that I can’t remember much of it.

When I look back on the journals I kept during that time, the edges are covered in red wine stains and the cursive is sprawling, sometimes unrecognizable. I wish I could tell you that writing this way was romantic, with me as a Hemingway-Highsmith hybrid, slurping gin and tonics and inhaling cigarettes while bent over a manual typewriter, drifting into the passion of the next sentence.

That would be bullshit.

Writing during that time in my life was far from romantic. It was a mess, with me wide legged on my floor at three in the morning trying not to barf while barely looking at the journal I was writing in, hurling broken paragraphs across the page into a blackout. I would wake up the next day and stare at these chicken scratches in disbelief. Often I was writing about pain, sexual assault, abuse, suicide. I told myself that the particulars were too hard to face sober, and as I’d strain to re-read what I couldn’t remember writing, the memory would hold.

That is what I remember happening, I would tell myself, fact checking my own memory, but what part of me actually wrote this down?

Alcoholism is not a writing tool. I wouldn’t have recommended it then; I don’t recommend it now. Yes, I wrote. Yes, I got out a first draft. There were parts of the memoir that felt frightening to write down, that felt raw and dangerous. And I honor that part of me every day, the part that was self medicating, the kid inside me who felt she had no choice.

But writing drunk was not an artistic choice; it was a slow suicide attempt. Foolishly, I thought moving to New York would help me curb the boozing I had spent years perfecting in Vancouver.

Instead, I was drinking alone in my apartment and calling my friends at all hours, friends who were starting to have sleeping kids and full time jobs. This behavior cut me off from community, and soon I was spending the last twenty dollars of my student loan on four bottles of cheap five dollar wine from the liquor store, the one where they have the bulletproof glass between you and the cash register. Which felt fine at the time because I somehow had the will to keeping making art.

Eventually, this went away. In the last six months of my drinking, I stopped being able to write. I mostly watched and re-watched documentaries about other artists. There was one I watched almost every morning called Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould.

Homesick for Canada, his Idea of North compositions would make me cry, and his failed love affair with Cornelia Foss a painful reminder of my own foibles. But it was the last twenty minutes of the film that got to me, watching his descent into addiction, a dependence on prescription medication that isolated him and then killed him.

By that point, my roommate was avoiding me and I had a friend in Winnipeg who would occasionally have time to talk me into passing out on the telephone, hanging up after waiting through a few minutes of silence. It was not my idea of living.

One morning I woke up so hungover I had to crawl to the bathroom with my eyes closed to start my now daily ritual of dry heaving into the toilet. I would pray and cry that something would kill me so I wouldn’t have to do it myself. That final morning, I went to the kitchen, got a butcher knife out of the drawer and brought its tip to my wrist, holding it there.

You can do this now, a voice said, or you can stop drinking.

It was a soft voice, more a reminder than an ultimatum. My whole body started to shake, more than it had been already and I dropped the knife. I can still remember the sound of it clanging against the brown kitchen tile. I haven’t had a drink since.

Recovery is where the book started to take shape.

At first, I worried that I somehow needed the booze, that without it I wouldn’t be in touch with that darkness, that part of me that I needed to touch in order to be genuine.

Which is also bullshit.

As I became more solid the book became solid, and that made it more genuine. Without the booze, I was able to pay attention for longer periods of time. Impulsivity became a tool that I could make space for but not get overwhelmed by. I still freewrite, still let myself careen across the page. Because that’s what the page is there for, for exploration. But now I have the skills to take that essential step back, to see what I’ve written and begin to articulate why I am writing a story, and how I want to present that story to a reader.

These are skills that a writer needs. We must be able to communicate to an agent, an editor, an interviewer. At first it was a struggle, just like everything in early sobriety is a struggle. Sitting with oneself, nothing between you and the page, is never easy. But once I was able to stop and to sit with what I was doing, the form would reveal itself to me.

I could see the construction of the narrative I was making and could start moving parts around to suit the story. I earned the trust of the creation. More than that, I could see what the writing needed moment by moment, like when I knew I needed to get the book copyedited before sending it out to an agent.

Later, when I started reaching out to agents, I could gauge whether or not I had made a genuine connection, and was able to choose an agent that I adore and can collaborate with. Handling literary rejection with grace helped to later contemplate and calmly negotiate notes from my editor.

I am now able to do the work because I am able to honor the work. One day at a time. One sentence at a time.

I actually wrote more sober than actively drinking and I’m glad I did. Because I felt the pleasures and pay off of writing and of publishing sober, it feels tangible to me. I know that I can do it again and do it without chemicals. Which makes me a more integrated human being and better writer. Writing saved my life when I was a drunk, I wouldn’t be alive without it. But it’s the exploration of craft and stories that also helps to keep me sober.

—

Tanya Marquardt is an award-winning playwright based in Brooklyn, author of the newly released memoir, STRAY: Memoir of a Runaway (published by Little A, Amazon’s literary and non-fiction imprint on September 1). Tanya’s story was recently featured in The Huffington Post and CBC, and her book has received early praise from Publishers Weekly.

Find out more about her on her website https://www.tanyamarquardt.com/

About STRAY: MEMOIR OF A RUNAWAY

“Marquardt’s memoir is a brutally honest reflection on her fraught adolescence and journey of self-realization.” – Publishers Weekly

“The highly expressive narrative is often brutal and raw, a combination of truth and penance, and it feels like a confession leading toward sanity and forgiveness.” -KIRKUS

After growing up in a dysfunctional and emotionally abusive home, Tanya Marquardt runs away on her sixteenth birthday. Her departure is an act of rebellion and survival – whatever she is heading toward has to be better than what she is leaving behind.

After growing up in a dysfunctional and emotionally abusive home, Tanya Marquardt runs away on her sixteenth birthday. Her departure is an act of rebellion and survival – whatever she is heading toward has to be better than what she is leaving behind.

Struggling with her inner demons, Tanya must learn to take care of herself during two chaotic years in the working-class mill town of Port Alberni, followed by the early-nineties underground goth scene in Vancouver, British Columbia. She finds a chosen family in her fellow misfits, and the bond they form is fierce and unflinching.

Told with raw honesty and strength, Stray reveals Tanya’s fight to embrace the vulnerable, beguiling parts of herself and heal the wounds of her past as she forges her own path to a new life.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing