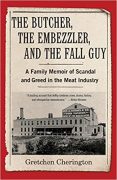

Writing The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy—A Family Memoir of Scandal and Greed in the Meat Industry

The genesis for my new book, The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy—A Family Memoir of Scandal and Greed in the Meat Industry came from listening to my father’s epic stories of his childhood in Austin, Minnesota. No snowstorm out there was less than five feet deep. The Cedar River which ran by his childhood home carried him on grand adventures involving campfires, rifles, and tramps jumping trains into the dense gloom of a nighttime fog. Friendships were made for life. Threaded through these scenic descriptions were three powerful men to which my father routinely returned his storytelling.

First was George A. Hormel who founded what is now the giant meatpacking conglomerate Hormel Foods. Starting as a poor and lowly “butcher” by trade he promised his mother that he aspired to be a real meatpacker. Second was my dad’s father, Alpha LaRue (A.L.) Eberhart, and the “fall guy” in my story. Already a sales legend at Swift & Company in Chicago, Hormel recruited A.L. to southern Minnesota in 1901 to help build his company. And third was Ransome J. Thomson, a wily farm boy hired by Hormel, who turned from bookkeeper to company comptroller, and over ten years, embezzled nearly $1.2 Million from the company coffers. With his takings he built a world-class chicken farm, then turned it into an amusement park in the middle of nowhere, to which 60,000 people traveled on weekends for entertainment.

As a kid, I took this all in, along with the roles my father ascribed to these men—A.L. was our hero who was horribly wronged by Hormel after being forced to resign under a “flimsy pretext” after the embezzlement was discovered. Hormel was relegated to the role of villain in the story, and Thomson got mixed reviews—my father was aghast at his deed but reveled in how managed to get away with it for so long.

As an adult, I built a long career working with CEOs and executives from mid-sized to Fortune 500 companies. My relationships with them were sometimes deep and long. I watched how they made decisions, took feedback, and built company culture. I never met one without flaws. Which got me rethinking what I thought I knew from my father’s stories about the butcher, the embezzler, and my grandfather.

To write the book I wanted to write, I couldn’t just rely on old newsprint and internet searches. I’m a strong believer in conversations with real people, close to the story. I wanted to try to figure out what happened a hundred years ago, even if it meant holding my family’s mythology up to a mirror or aggravating the protective oversight of a brand name company.

In working with CEOs, I’d been given a rare opportunity to learn deeply about them from those around them. Frequently asked to interview their direct reports, I developed skills in creating safe spaces for them to talk honestly, and in asking just the right question at the just right moment. This required a lot of trust building with each person. I brought those skills with me on three research trips to Austin for live conversations as well as through hundreds of emails, letters, and phone calls. I shared my curiosity (some might call it my obsession) along with my vulnerability in not having all the answers. I listened, asked a lot of follow-ups, and held off on drawing conclusions right up to my print deadline.

Still, this initially felt like new territory. I didn’t have the cover of a CEO’s contract, and, though an heir to one of the protagonists, I was clearly from “outside.” Austin is first and foremost a company town, and company towns protect their brands. I was bringing an east-coast food snobbery to a place where restaurant menus carried only Hormel meats. I was clueless that a high school could pack 4000 cheering fans into every Friday night football game. I was surprised, honestly, at how much I liked the small Midwestern city of Austin and its people. But then whenever I meet someone quite different from me, I usually find great similarities if we’re engaged in real conversation.

Even if willing to question my family stories, I knew I would serve as its ambassador, too, which required me to keep them abreast of my findings along the way.

In Austin, I carried a personal but professional stance, honoring both my grandparents and the Hormel company that had provided their opportunity in 1901. The city and its people helped me discover my own love for the grandparents I’d never known, both having died long before I was born. I could see where my own passion for wild places came from when I canoed up the Cedar River five miles to Ramsey, Minnesota. I better comprehended the appeal of southern Minnesota’s beautiful rolling countryside on an autumn trip when thousands of jet black acres were turned over for winter. I learned about the role of successive waves of immigrants in the brutal work of cutting and packing our meats—from the Germans and Dutch in my grandfather’s era to the Mexican, Middle Eastern, and Africans in mine.

Without gaining the trust of dozens of Austinians, I could not have found the information I needed to write this multi-layered story, nor faced my family’s mythology for what it was. Austin moved from myth to a real place whose people didn’t shy away from the contradictions they live with. If I’d grown up with a large dose of animus toward George Hormel, most of that rubbed off in the course of my research. If I’d been raised thinking of my grandfather as hoisted on a pedestal, the pedestal found its way back to earth. And if I doubted parts of my family stories, I learned not to doubt all of them, as in my grandfather’s great warmth, his life-long loyalty to friends and theirs to him, his real joy in living, each of which was validated.

Humans are endlessly complex—hence rich fodder for writers—and no one is purely a villain or a hero. A.L., George Hormel, the Hormel company’s bankers and auditors, and everyone in southern Minnesota lived in denial about the embezzler, and that’s a bad location for any leaders of companies. The best of the CEOs I worked with used to tell me they’d rather face a lousy truth now, than wish they had when it was worse, later. The Hormel company’s denial in the early 1900s nearly caused its own collapse.

Truth can be elusive and our interpretation of it changes with time. I’ve long felt the best stories come from authors who rid themselves of assumptions and denial. This book was rich ground for me to face mine. Then we can let our characters and stories reveal themselves.

With a live launch in Austin, I look forward to seeing friends under that broad, arching Minnesota sky, and if the trip is anything like the last three, I won’t be surprised if I come away having learned something else new about what really happened to my grandfather a century ago.

—

The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy: A Family Memoir of Scandal and Greed in the Meat Industry

Three powerful men converge on the banks of the Red Cedar River in the early 1900s in southern Minnesota—George Albert Hormel, founder of what will become the $10 billion food conglomerate Hormel Foods; Alpha LaRue Eberhart, the author’s paternal grandfather and Hormel’s Executive Vice President and Corporate Secretary; and Ransome Josiah Thomson, Hormel’s comptroller. Over ten years, Thomson will embezzle $1.2 million from the company’s coffers, nearly bringing the company to its knees.

Three powerful men converge on the banks of the Red Cedar River in the early 1900s in southern Minnesota—George Albert Hormel, founder of what will become the $10 billion food conglomerate Hormel Foods; Alpha LaRue Eberhart, the author’s paternal grandfather and Hormel’s Executive Vice President and Corporate Secretary; and Ransome Josiah Thomson, Hormel’s comptroller. Over ten years, Thomson will embezzle $1.2 million from the company’s coffers, nearly bringing the company to its knees.

The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy opens in 1922 as George Hormel calls Eberhart into his office and demands his resignation. Hailed as the true leader of the company he’d helped Hormel build—is Eberhart complicit in the embezzlement? Far worse than losing his job and the great wealth he’d rightfully accumulated is that his beloved young wife, Lena, is dying while their three children grieve alongside. Of course, his story doesn’t end there.

In scale both intimate and grand, Cherington deftly weaves the histories of Hormel, Eberhart, and Thomson within the sweeping landscape of our country’s early industries, along with keen observations about business leaders gleaned from her thirty-five-year career advising top company executives. The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy equally chronicles Cherington’s journey from blind faith in family lore to a nuanced consideration of the three men’s great strengths and flaws—and a multilayered, thoughtful exploration of the ways we all must contend with the mythology of powerful men, our reverence for heroes, and the legacy of a complicated past.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing