Coming Out of the Spy Family Closet

Coming Out of the Spy Family Closet

Publishing my memoir Spy Daughter, Queer Girl entailed 17 years of facing my fears. Being the daughter of a spy means keeping secrets. It’s built into spy family culture. It wasn’t until I attended a writing workshop taught by novelist Dorothy Allison, author of Bastard Out of Carolina, that I realized I had to write about my father’s silence. And mine.

Publishing my memoir Spy Daughter, Queer Girl entailed 17 years of facing my fears. Being the daughter of a spy means keeping secrets. It’s built into spy family culture. It wasn’t until I attended a writing workshop taught by novelist Dorothy Allison, author of Bastard Out of Carolina, that I realized I had to write about my father’s silence. And mine.

Allison’s message to me was to write into our fear and learn how to use it. She said it was a tool I should sharpen. I had brought an essay to her workshop about my complicated feelings for my father and his work for the CIA. I asked Allison if it was ready to submit for publication, she smiled wryly and said it was a book.

This stunned me. Gradually, I realized she was right. After a few stops and starts, I began to write my book. Every word I wrote over the next 17 years was an exercise in trying to confront the fears that came up when I tried to tell my truth—about being gay and about having a secretive father. I told myself that I didn’t have to show my story to anyone. I could throw it all away later if I chose to. Still, I always felt like my father could mysteriously still see what I was working on. It was as if I had no place to hide.

Being the child of a spy means being born into a world of secrets. This wasn’t the case for my father. He joined the CIA when he was in his youth. It was a job, one he felt passionately about and had interviewed for: a choice. He was paid and then after nearly 32 years he retired.

I was in my late twenties and remember the day he called to tell me. I picked up the phone and after a few minutes of our usual small talk, he announced his plans to retire. I couldn’t process this. I gripped the phone tightly. Who was this father? The one I had grown up with was person of secrets. I couldn’t imagine him leaving his profession, one that was much more like a calling. What he said next was even more surprising—that he wanted to teach. I tried but failed to imagine my father telling his secret to a room full of students. It wasn’t what I was used to.

In order for him to become a teacher and to speak openly about having worked for the CIA, he had to undergo an agency sanctioned process of having his covers removed. To do this, the agency scrutinized everyone he had ever worked with in the field. Would any mission or individual be endangered if he came out of his spy closet? If the answer was yes, then clearance would be denied and he would have to remain silent.

The agency did ultimately clear him and he went on to teach at public and private universities. It was a defining moment, one that allowed him to live more openly. But it was also a defining moment for me. If he hadn’t gone through the process of having his covers removed I wouldn’t have been free to tell my story either. Instead, I would have had to remain inside my spy daughter closet forever. I could tell people I trusted but I could never have written about it? How free could I have been if that topic had stayed suppressed within me and disallowed?

I was forty when I attended Allison’s workshop and began writing my memoir. I wrote obsessively every day for years. Every time I sat down at my writer’s desk, I felt like a traitor. Only a bad daughter reveals her father’s secret. It didn’t matter that it was no longer a secret by then. Describing what it was like to come out as a lesbian was just as hard. I hadn’t given myself full permission to tell either of my secrets yet.

Over the course of the next decade and a half, I wrote and revised. I sent out queries to agents and even landed one. Looking back, I am grateful it didn’t work out with this person. The story wasn’t ready. I wasn’t ready.

I kept going. Each day that I wrote, I grew freer. The story clarified. I met with scholars, researched and had illuminating conversations with my father too. The process of working on this project transformed our relationship. He shifted from not accepting my sexuality to eventually greeting my wife warmly during a visit to his home. I changed too. My research led me to better understanding my father’s work. I was still critical of many of the CIA’s missions but there was nuance now. The agency was no longer a monolith.

Although I resubmitted to agents again, some wanted me to write more of a spy thriller. I kept it a daughter’s story. When I wasn’t able to find another agent, I hired an editor to help me polish my manuscript. I joined writing groups. Eventually, I sent it out again, this time directly to small presses. Spy Daughter, Queer Girl was selected by Latah Books, a press that felt as passionately about my book as I did.

Finally, it was time to tell my story.

—

Leslie is a journalist and essayist. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Independent, Salon, Huffington Post, Ms., Greek Reporter, and the San Francisco Chronicle. Leslie is a regular contributor to Ms. and teaches writing and study skills to high school students. She lives in Oakland with her comic book writer/lawyer wife and a trio of cats. Her memoir Spy Daughter, Queer Girl: In Search of Truth and Acceptance in a Family of Secrets was published by Latah Books in October 2022.

Leslie is a journalist and essayist. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Independent, Salon, Huffington Post, Ms., Greek Reporter, and the San Francisco Chronicle. Leslie is a regular contributor to Ms. and teaches writing and study skills to high school students. She lives in Oakland with her comic book writer/lawyer wife and a trio of cats. Her memoir Spy Daughter, Queer Girl: In Search of Truth and Acceptance in a Family of Secrets was published by Latah Books in October 2022.

For Leslie Absher, secrecy is just another member of the family. Throughout childhood, her father’s shadowy government job was ill-defined, her mother’s mental health stayed off limits–even her queer identity remained hidden from her family and unacknowledged by Leslie herself.

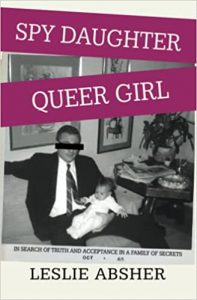

SPY DAUGHTER, QUEER GIRL

In SPY DAUGHTER, QUEER GIRL, Absher pursues the truth: of her family, her identity, and her father’s role in Greece’s CIA-backed junta. As a guide, Absher brings readers to the shade of plane trees in Greece, to queer discos in Boston, and to tense diner meals with her aging CIA father. As a memoirist, Absher renders a lifetime of hazy, shapeshifting truths in high-definition vibrance.

Infused with a journalist’s tenacity and a daughter’s open heart, this book recounts a decades’ long process of discovery and the reason why the facts should matter to us all.

Leslie Absher is a journalist and personal essay writer. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Independent, Salon, Huffington Post, Ms., Greek Reporter, and the San Francisco Chronicle.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing