Going to the Writing Gym: On Writing Between Modes

When we go to the gym, we do a variety of exercise routines to strengthen different muscles. Likewise, writing in different modes can stretch a range of writer muscles.

When we go to the gym, we do a variety of exercise routines to strengthen different muscles. Likewise, writing in different modes can stretch a range of writer muscles.

Fiction (particularly genre fiction) prioritizes reader engagement through plot, movement and voice. Ideas tend to be embodied through plot movements, dialogue and character arcs. Because fiction is a more time-consuming commitment to read than poetry, it has to hook its readers to keep turning the pages. There are often stakes (whether emotional or physical) that keep us invested as readers. Writers form and reinforce the arguments of their narratives through well-developed characters, the presence or subversion of archetypes, engaging storylines, and meaningful endings.

Poetry however has different priorities. A poetry professor of mine described poetry not as a narrative or story but as recreating an experience for the reader. While fiction is often described as having a bell-curved narrative (a problem escalating to a climax descending to a resolution), poetry is more of a diagonal line of images and observations leading up to a realization. Poetry prioritizes images and sounds, and with its smaller real-estate, poets have to think about how they use space very differently than fiction writers. Ideas in poems tend to be embodied through form, imagery, sound and voltas of realization. Poetic forms make a poet think about how they can use devices as subtle as shape, sound, and repetition to reinforce the argument of their piece in meaningful ways.

Writing fiction works different muscles than writing poetry. I find that when I haven’t done one for a while, it’s uncomfortable, like doing bench presses after the holidays. I’m sore for a few days, and anxiety and doubt flood my mind. What was I thinking, trying to write poetry after this long? How am I supposed to go back to writing 50k+ words when I’ve been writing haiku for the past two years? Yet once I push past through the pain, I find I’m stronger for it. When I write, I’m not completely dependent on one set of muscles to do all the work. I’m not just viewing a scene from one point of view. Instead I have an entire body, a range of movements that can approach a story from all sorts of angles and perspectives.

When I write fiction, I learn how to tell a story and keep a reader engaged. I think on the macro level, looking at how I can create a strong structure for an overall piece. I think about how each scene builds off the last, propelling the reader forward. When I write poetry, I learn how to look at the micro level, thinking carefully about word choice, musical sounds, and haunting images. I think about how I can show and not tell what’s going on to my reader.

When I write fiction, I learn how to tell a story and keep a reader engaged. I think on the macro level, looking at how I can create a strong structure for an overall piece. I think about how each scene builds off the last, propelling the reader forward. When I write poetry, I learn how to look at the micro level, thinking carefully about word choice, musical sounds, and haunting images. I think about how I can show and not tell what’s going on to my reader.

What this means is that when I revisit my poems after working on novels, I can take an aerial view on my old drafts. Where is this poem trying to go, I ask myself? What did I discover through this process? What do I want my reader to take away from this observation? I think much more about the momentum between stanzas, and when looking at a collection, the momentum between poems. When I revisit my novels after working on poetry for a while, I’m much more attentive to the little details. My scenes become more vivid, and my characters say surprising things, the realizations that come from the objects and images around them. And most importantly, my fiction feels more real after working on poetry. Poetry makes me slow down, take in the world around me, and process through attending to the details. It’s the details that make our worlds feel real, and when we have to practice attending to these, it comes through even more powerfully on the page.

If you tend to write in one genre, I encourage you to explore beyond your comfort zone. If you write literary fiction, try taking a course in genre fiction. If you do poetry, try prose. If you write free verse, try studying poetic forms. You never know what writing tools you’ll glean from this experience and how it will make your craft muscles grow.

—

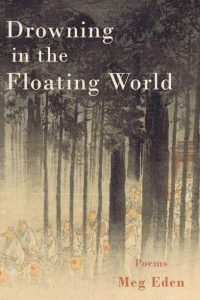

Meg Eden’s work is published or forthcoming in magazines including Prairie Schooner, Poetry Northwest, Crab Orchard Review, RHINO and CV2. She teaches creative writing at Anne Arundel Community College. She is the author of five poetry chapbooks, the novel “Post-High School Reality Quest” (2017), and the forthcoming poetry collection “Drowning in the Floating World” (2020). She runs the Magfest MAGES Library blog, which posts accessible academic articles about video games (https://super.magfest.org/mages-blog). Find her online at www.megedenbooks.com or on Twitter at @ConfusedNarwhal.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips