Interview with Sigrid Nunez

Photo by Nancy Crampton

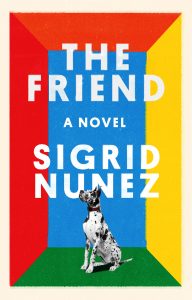

Journalist Jenna Orkin interviews Nunez about the unusual level of intimacy she achieves in her work as well as the themes of the novel which range from suicide to writing teachers and students.

In your latest novel, The Friend, you’ve said that you were striving for the intimate tone of a letter. You certainly achieved it. As with almost all your books, the reader has the sense of talking to a good friend who’s being as open as possible in telling her story. I say “almost” as a hedge; in fact I can’t think of a book in which you don’t convey this sense of intimacy.

Do you ever have misgivings about doing this? The poet Elizabeth Bishop wrote, “There’s nothing more embarrassing than being a poet.” Could one say the same thing about novelists? Is there a literary equivalent to doing a nude scene?

I don’t have misgivings about the intimate tone. If I did have such misgivings, I wouldn’t be able to write the book. I’d have to find another tone. About the Bishop quote, I’ve heard other poets say the same thing, or something similar, and many fiction writers have also expressed the feeling that there is something shameful about publishing a book. I know a filmmaker who said that once his film had been released he felt covered with shame (and we’re talking about a very fine and successful film). But I don’t think it has to do with the literary equivalent of a nude scene. It’s only too obvious why an actor might find it difficult to appear unclothed, and perhaps simulating sex, for the whole world to see. But the embarrassment a writer feels about publishing a book can be about any book, not just a self-revealing memoir or an autobiographical story; it’s not about that kind of explicit self-exposure or loss of privacy. It’s the idea of putting one’s work out there at all that brings a sense of shame.

Along the same lines, have you ever regretted anything you wrote? (This is the Barbara Walters question which perhaps I should regret. But one has to try.)

If we’re talking about work I’ve written and published, I don’t have any regrets.

The plot of The Friend concerns a writer/mentor who kills himself, leaving the narrator his Great Dane. But the essence of the book may well lie in the detours you take into such diverse subjects as writing teachers and students; and suicide among writers, particularly those who favor the first person. The amount of reading and research you must have done to unearth these facts is breathtaking. (A rhetorical question: How did you find out that serial killer Ted Bundy used to man a suicide hotline?!) But going back to the higher incidence of suicide among writers, and leaving aside the usual psychoanalytic explanations of bi-polar disorder or an overlap between creativity and “madness,” do you have any insight into why the suicide rate among writers is, in fact, twice as high as among the general public?

The fact about Bundy is from a book called The Stranger Beside Me. By utterly amazing coincidence, the author Ann Rule, who happens to be a true-crime writer, worked on a crisis hotline with Ted Bundy.

I don’t really know why the suicide rate among writers (and other artists, I believe) should be so high. It may just be that the type of person who becomes an artist is also the type of person who is susceptible to the emotional disturbances that can lead to self-destruction. It should be said, though, that suicide is on the rise among many groups of people, and it has been for some time.

You’ve said in other interviews that while you were writing The Friend, a writer friend of yours did, in fact, kill himself. I also knew a suicide about as well as one can know another person.

My friend seemed to be a prime example of the theory that depression is anger turned inwards. While he was living in my apartment, he had himself committed to Bellevue over New Year’s, saying he was afraid that otherwise he might kill himself. But I had the distinct feeling that he was at least as afraid he might kill me.

Although outstanding in his work, he had no close personal relationships. When he met someone he liked, there would be an initial honeymoon period (“my new best friend”) but after a year or so, he’d find some reason to sever all ties, and dramatically.

Does this resonate with your experience of the suicides you’ve known? Could you talk about one or two of them?

In fact, I’d just finished my novel when my friend killed himself, though it wouldn’t be published for another year or so. What you say about your friend did not apply to my own friend, but the kind of mental disorder that you’re describing is certainly something I’ve seen in other troubled people. On the other hand, I can think of any number of suicides who don’t fit this profile at all. That’s the thing: all kinds of people take their own lives and often people who knew them well are completely shocked because the suicide did not appear to be suicidal or seriously depressed or even especially unhappy.

In the book, you describe how, when you were young, writing was considered a calling rather than a way to make a living whereas your students these days have a more mundane approach. (“I’ve shelled out so much money for this course, I have to make a bundle to pay off my student loan.”)

Elsewhere, in an interview, you talk about “strays,” people who don’t participate in life’s usual rites of passage such as marriage and children. You predict that we’ll be seeing more of them and that they may be predominantly women.

Would you say that some of these strays are in fact following a calling? Are they the modern equivalent of the nuns of the past, the difference being that nuns address themselves to God while the writer or other person with a vocation addresses herself to the public?

I should say that I didn’t mean to suggest that every aspiring writer back in the day thought of writing as a vocation rather than as a career. However, what’s much more common today is a way of regarding writing more as a lifestyle choice than as a calling. Not the “anguish and travail” described by Faulkner but a means of getting attention, or a means of making one’s life more varied and interesting or of raising one’s self-esteem. There is the sense now that writing is open to all, you don’t need to have any special gift or calling, and that is not how people used to think about writing when I was a student.

The idea of certain people being “strays” had nothing to do with writing or any kind of calling for me. Here I was thinking of something Renata Adler writes about in her marvelous novel Pitch Dark. She was talking about people who remain single, who might have normal lives with lots of friends, but never really become part of life in the way most other people do. When I said I thought there’d be more of such people in future and that they were likely to be mostly women it was only because I think more and more women are going to choose to remain single and childless in future. I wasn’t thinking about these strays as writers or as persons of any particular kind of vocation, though.

What are some other differences that you see between students nowadays and your classmates when you studied under Elizabeth Hardwick at Barnard? What have you learned from your students?

It used to be a given that if you wanted to be a writer it was partly because you were a reader, a serious reader, someone who loved books. Nowadays I am no longer surprised when a writing student announces that they don’t read much at all, that in fact they don’t like reading, that they don’t want to read other people’s work, they only want other people to read their work.

My teaching requires me to do a lot of editorial work on student manuscripts, and I learn from their work all the time. I have to read very closely to try to determine what works and what doesn’t work and how the writing might be changed to do a more effective job of telling the story the student wants to tell. I learn an endless amount about all aspects of writing from doing this.

Why did you say that you believe For Rouenna to be your best book? (I realize your view may have changed since that interview.)

I still think For Rouenna may be my best book. The reason is that I think it’s the book of mine that most successfully fulfilled the intentions I had when I started writing it. It came closest to what I was hoping for.

You’ve spoken about your interest in film. Have any particular films influenced your work? Are there techniques used in film that you’ve adapted to your writing?

As a writer and not a filmmaker what I take from films are the narratives. It’s not about techniques but rather about characters and their personalities and their stories.

I believe The Friend is going to be made into a movie. What are you learning about the translation from one art form to the other?

The Friend has been optioned for film. The screenplay is being written at this moment but I haven’t seen it. I do have faith that a very good film could be made out of the novel. I also know that there will inevitably be changes to the original, and of course I’m very curious to see what those are.

—

Jenna Orkin is a former student of Sigrid Nunez and the author of Ground Zero Wars: The Fight to Reveal the Lies of the EPA in the Wake of 9/11

Sigrid Nunez has published seven novels, including A Feather on the Breath of God, The Last of Her Kind, and, most recently, The Friend, which won the 2018 National Book Award for fiction and was a finalist for the 2019 Simpson/Joyce Carol Oates Prize. She is also the author of Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag. Nunez’s other honors and awards include four Pushcart Prizes, a Whiting Award, a Berlin Prize Fellowship, and two awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters: the Rosenthal Foundation Award and the Rome Prize in Literature. You can learn more at sigridnunez.com.

When a woman unexpectedly loses her lifelong best friend and mentor, she finds herself burdened with the unwanted dog he has left behind. Her own battle against grief is intensified by the mute suffering of the dog, a huge Great Dane traumatized by the inexplicable disappearance of its master, and by the threat of eviction: dogs are prohibited in her apartment building.

When a woman unexpectedly loses her lifelong best friend and mentor, she finds herself burdened with the unwanted dog he has left behind. Her own battle against grief is intensified by the mute suffering of the dog, a huge Great Dane traumatized by the inexplicable disappearance of its master, and by the threat of eviction: dogs are prohibited in her apartment building.

While others worry that grief has made her a victim of magical thinking, the woman refuses to be separated from the dog except for brief periods of time. Isolated from the rest of the world, increasingly obsessed with the dog’s care, determined to read its mind and fathom its heart, she comes dangerously close to unraveling. But while troubles abound, rich and surprising rewards lie in store for both of them.

Elegiac and searching, The Friend is both a meditation on loss and a celebration of human-canine devotion.

Named by The New York Times as a 2018 Literary Event not to be missed and a Most Anticipated Title of 2018 by TimeOut, BuzzFeed, BookRiot, The Millions, Bustle, Vulture, Harper’s Bazaar, PopSugar, Shondaland, Paste Magazine, The Huffington Post, The Rumpus, Electric Literature, Chicago Reader, Bookhub, The Hippo: New Hampshire’s Weekly, Fast Company, Garden and Gun.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, Interviews, On Writing