Susan Vreeland: Fiction and Art

Sometimes I’m baffled about what Tracy Chevalier and I set in motion in 1999 with our two Vermeer novels, my Girl in Hyacinth Blue and her Girl with a Pearl Earring. They both hit the New York Times Bestseller List about the same time, and ever since, there has been a flurry of ekphrasic literature, meaning in this case, fiction which alludes to a work of art. I’ve recorded at least fifty novels in this category on my Goodreads blogs.

Sometimes I’m baffled about what Tracy Chevalier and I set in motion in 1999 with our two Vermeer novels, my Girl in Hyacinth Blue and her Girl with a Pearl Earring. They both hit the New York Times Bestseller List about the same time, and ever since, there has been a flurry of ekphrasic literature, meaning in this case, fiction which alludes to a work of art. I’ve recorded at least fifty novels in this category on my Goodreads blogs.

In addition, I must honor those classic works that preceded this phenomenon: The Agony and the Ecstasy about Michelangelo, Lust for Life about van Gogh, and Depths of Glory about Camille Pissarro, all by Irving Stone. I devoured those novels, and remain grateful to Stone for thus giving me permission to write fiction using a real artist.

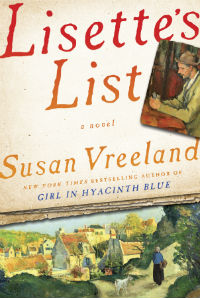

There followed six novels of mine, culminating in Lisette’s List, that depicted Johannes Vermeer, Artemisia Gentileschi, Auguste Renoir, Emily Carr, Louis Comfort Tiffany and Clara Driscoll, and one story collection that featured Claude Monet, Éduard Manet, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Vincent van Gogh, and Amadeo Modigliani.

How can any visually responsive, historically curious, lover of paintings resist wanting to read or write a novel with an art element? For my part, I don’t see how. The terrain is unlimited, the approaches varied.

Consider these story lines: the researched history of a painter’s career; the imagined events of a painter’s life; the experience of a wife, muse, model, or mistress of a painter; the focus on the making of a single painting; an invented painting; a loose echo of a historic painter; a completely invented painter; a real painter but imagined characters surrounding him; the fate of a gallery or museum; a theft, a forgery, a romp; a journey through the provenance of a painting. I’ve used six of these approaches.

To what do we owe the appeal for writers to build a narrative on art? I think the attraction must have its seed in a deep-seated love of art or of a single work of art, a particular style, a painter’s vibrant or struggling life, or a fascination with the time period that produced the work. The urge is not new. In the sixteenth century, Giorgio Vasari, Florentine painter and writer, was the first recorder of lives of great artists of the western hemisphere.

He was accurate in most cases, inventive in others. But what did Vasari miss that transpired after his death? What struggles must there must have been to develop a new style, to display the way a painter sees, to reveal the interior of his mind, to express the soul of an epoch? What physical and mental exhaustion, what frustration at limited skills, what despair at creeping age, financial ruin, doubt, ridicule, scorn was there?

What ecstasy bubbled up frothing and pure in finding the perfect model or muse? What energy was required to fight against tradition-bound critics and the capricious power of their pens? How could one handle distractions of grief, love, addiction, spiritual seeking so as not to abort or damage one’s work? And what about the story behind a painting so well known that its fame precedes the novel?

What ecstasy bubbled up frothing and pure in finding the perfect model or muse? What energy was required to fight against tradition-bound critics and the capricious power of their pens? How could one handle distractions of grief, love, addiction, spiritual seeking so as not to abort or damage one’s work? And what about the story behind a painting so well known that its fame precedes the novel?

There are also the intriguing explorations of those personages related to a painter–a wife, lover, daughter, model. Paintings as commodities appeal to the mystery and thriller writer gleaning story from heists, forgeries, secrets, while invented painters allow the writer to explore regions of the human heart, the spiritual search, the development of identity. In some of these, the art is a central feature of the narrative. In others, it’s almost incidental, and teases us by its shy and limited appearance. Any of these elements can provide substance for a narrative.

And when one dips into what the artists have been recorded as saying, our appreciation for their genius and spirituality enhances the treasures they have given us. For example, just considering the artists featured in Lisette’s List, Pissarro said “Everything is beautiful. The important thing is to know how to interpret it.” And from Cézanne: “Art is a religion. Its goal is the elevation of thought.” And this profound sentiment of Marc Chagall: “Only love interests me, and I am only in contact with things that revolve around love. In the arts, as in life, everything is possible provided it is based on love.” Is it any wonder so many writers have joined me in turning to art as the foundation for literature?

—

Susan Vreeland is an internationally known author of art-related historical fiction. Vreeland has written four New York Times best sellers — “The Passion of Artemisia,” “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” “Clara and Mr. Tiffany” and “Girl in Hyacinth Blue,” which was adapted into a Hallmark Hall of Fame TV drama. Her newest novel, “Lisette’s List”, presents one woman’s yearning for art at a time when her family’s collection of paintings had to be hidden in the south of France from Nazi art thieves.

Vreeland’s novels have been translated into 26 languages and have frequently been selected as Book Sense Picks. She was a high school English teacher in San Diego for 30 years. Find out more about Susan on her website http://www.svreeland.com/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Dear Susan,

You have inspired me! Truly, the knit-together bond between art and writing is so clear that I wonder why I haven’t seen it sooner? When I go to our local Art Gallery, I sit before the same four of five pictures because they touch my heart. Must read Girl in Hyacinth Blue. Thanks so much. Mary Latela

Thanks for a thought provoking post. This really chimes with me! My novel, The Art Forger’s Daughter is a celebration of art and its impact on the world in times of crisis. I love the stories paintings can tell and the mystery of their interpretation.

Thank you Diana for your incisive piece which resonated so much with me. I too remember reading The Agony and the Ecstasy and Lust For Life and rushing to look again at the work of these artists.

The Chevalier novel was interesting in that it focused on a particular painting and, through the gift of fiction, incorporated the inner life of the model.

Now I will rush to read your novels…

It occurs to me that the way we look at a particular painting is to try to tell ourselves its story,to give the painting a narrative form which we can access through our literary imaginations.

I loved writing my novel Gabriel Merchant, now in its second edition, inspired by the paintings of two gifted working class miners who were subtle artists. w.

I’m an artist as well as a writer so I’m drawn to books like yours and Tracy Chevalier’s. Patrick Gale’s Notes on an Exhibition was terrific too. In my own writing, I find I naturally use art as visual references and have written characters who are artists or who have synaesthesia or who see the world pictorially. Yet to write about a specific artist or painting but the idea is intriguing.

Great blog, thanks!

Great essay about a topic very near to my heart. Thank you, Susan Vreeland.

A wonderful post re: something near and dear to me, namely, ekphrasis and the myriad ways art can find itself in fiction. Many years ago, I read an exquisite short novel by Eva Figes, ‘Light.’ Interesting to discover that the 2007 reprint contains a subtitle: ‘With Monet at Giverny’ (completely unnecessary, to my thinking). Couldn’t help but recall it when I looked at your list — a treasure trove, indeed — on Goodreads.