The Allophone Writer

Eva Moreda

I was in my third year at high school when my Galician Literature teacher gave us a lecture on allophone poets – that is, those non-native speakers who had written poetry in Galician, including a couple of internationally known names such as Federico García Lorca. I remember thinking at the time that writing literature in a non-native language was a Herculean task accessible only to the greatest minds.

Yet, fifteen years later, I find myself writing fiction in a non-native language – English. I don’t claim to do it well, but, since I took the plunge and started writing a novel in English one and a half years ago, I have discovered that I can do it. Perseverance, an obsession with the minutiae of language and an English native close friend or partner do help – greatly.

Of course, being an academic in an Arts and Humanities subject, I was no strange to writing in English on a regular basis. Academic writing is often presented as arid, formulaic, abstruse – the opposite of everything creative writing should be.

Although I do not dispute that this may be true in some corners of academia, it does not entirely match my experience: when an author sends an article or a book proposal to a journal or a publishing house for consideration, it typically goes to at least two anonymous reviewers who will comment on the significance of the research for the broader discipline, the soundness of the argument, the accuracy of the facts – but also on whether all of the former is being appropriately conveyed to the reader in clear and fluid prose.

I now feel fortunate that some of my reviewers were extremely fastidious with language – although I certainly didn’t when they delighted in picking up every problem with not-so-obvious false friends and with my preference for nominal over verbal style! As in: ‘When it became clear again that the war wasn’t going to end soon, a decision was quickly taken – I was to stay at school’ – an actual example I have just found in my novel manuscript.

Nominal style certainly has a place in English, and in fact its slight pomposity may be more advisable than the plainer verbal style in certain contexts, but my experience with academic reviewers led me to become aware that, like many speakers of Romance languages, I tend to use it more often than English native speakers do.

Wordiness is another of my sins. For some reason –and I am aware that this is a generalization-, writers in languages such as Galician, Spanish or Italian tend to think that more is more: you cannot possibly have anything valid to express unless you say it in an extremely long-winded way. To prove it, here’s another example I have just picked up from my manuscript: ‘before I could provide an answer’ does not really make such a difference with respect to ‘before I could answer’.

I am currently on the fourth draft of my English-language novel and I keep finding mistakes like this. It doesn’t frustrate me, though: I prefer to focus on how much progress I’ve made since I first put pen to paper, secretly thinking that writing literature in a foreign language was indeed unachievable and I would give up after one week.

In the last eighteen months, I have developed an awareness of words, a proximity to my writing I had never thought possible – despite being a writer in various genres, a reader in even more genres and a translator. I now know that I use nominal style too much and I tend to be long-winded. Nevertheless, I also know that these are not flaws to be unconditionally outcast from my writing: I know that Galician tends to be nominal and long-winded in contexts in which English is not, and being deliberately nominal and long-winded can therefore help me make a point, define a character, attract the reader’s attentions to my writing if I so wish.

Being constantly aware of your writing, not being able to relax, may seem limiting and unnerving to some. For me, it is liberating – how can it not be, if I feel more in control of language than ever? Before I made the decision to switch to English as my main language for creative writing, I felt as if my literary writing in Galician had hit a wall. I felt unable to connect with the words, to make them do what I wanted them to do. My writing was full of clichés and stock phrases, words I had borrowed from other writers, and I was unable to speak my own way.

Being constantly aware of your writing, not being able to relax, may seem limiting and unnerving to some. For me, it is liberating – how can it not be, if I feel more in control of language than ever? Before I made the decision to switch to English as my main language for creative writing, I felt as if my literary writing in Galician had hit a wall. I felt unable to connect with the words, to make them do what I wanted them to do. My writing was full of clichés and stock phrases, words I had borrowed from other writers, and I was unable to speak my own way.

Even the most harmless words – folerpa (snowflake), bolboreta (butterfly), senlleiro (illustrious) – seemed trite and tired, having repeatedly been awarded a principal place in literary language for various. My creative block may have been the consequence of more than eight years living outside Galicia, with no day-to-day contact with the language I used to write in; my command of Galicia, I admit with more than a certain shame, was starting to get rusty. Or it may be that in a smaller –in number of speakers- language and literature connotations are more difficult to elude: with everyone echoing such connotations, adding to them, it seems difficult to migrate to a different province in the same way I feel I can do with English.

I try not to be too optimistic, though. Most of my creative writing in English has focused on my novel; it is a first-person narrative and by now I know the narrator well, I know how she speaks and talks, which words and combinations of words reflect her personality. When I tried to write other things – short stories, travel writing, fragments from a second novel -, I felt I was back to square one: I had to tame English again. Much of what I’ve learnt won’t be of my help once I finish my novel and move on to something else – but I cannot wait for it to start again.

—

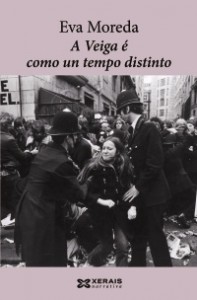

Eva Moreda comes from Galicia but lives in Scotland, where she teaches and researches in the field of Music History at the University of Glasgow. She is a published, prize-winning novelist in Galician and has only recently started using English as her main writing language; she is currently working on two academic monographs about music under the Franco regime and a novel set during the Second World War. A short fiction piece was recently published in the anthology Writers at the Hunterian.

Follow her on twitter @TheDrRodriguez

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

I really relate to what you say, especially about it being liberating. I started creative writing when we came to live in Wales and I learned the Welsh language – partly kick-started through having a Welsh tutor who was also a fantastic creative writing teacher, but mainly because writing in another language opened the creative doors for all the reasons you and Gill James say and because somehow it felt like a “safety net”, a different world. I write mainly in English (my native language) now, but spent many years with Welsh as my “creative” language.

I can relate to this. I used to teach languages and dared student to write creatively in their new language as a way of becoming more confident. It was about making the most of what you know.

I gradually realized that it also helped them to free up their mother tongue.

Interestingly, too, what is a cliche in one language can actually work very well in another because it is fresher.

This is a wonderful explanation of the difficulties – and pleasures! – of writing in a foreign language. Thank you so much for sharing.