The Art of Co-Authorship

Photo by Rosalind Hobley

When we launched our website SomethingRhymed.com, we set ourselves a yearlong goal to research and write about a different pair of female writer friends every month.

Well-wishers cautioned that we might struggle to find a dozen such duos, and this was something that worried us too. We knew all about Wordsworth and, Byron and Shelley, Hemingway and Fitzgerald. But we struggled to name many female writer friends. And so, we wrote a piece for this site asking readers to send in their suggestions.

Much to our delight, the tip-offs came in thick and fast. Passing references in biographies marked the beginning of research trails. Could we discover more about Anne Sharp, the amateur playwright friend of Jane Austen, who gets only a fleeting mention in accounts of the famed novelist’s life? Did the outspoken feminist author Mary Taylor influence the work of her school friend Charlotte Brontë? Did we know that George Eliot had maintained a lively correspondence with Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Were Virginia Woolf and fellow modernist Katherine Mansfield dear friends or bitter foes?

We received so many interesting leads that we’ve accumulated sufficient pairs to keep the website going over three years on, and we’ve also shared our discoveries in co-written articles for newspapers and magazines.

In the early days of writing about female friendship, we would stay at each other’s places for days on end, sitting side-by-side at the same desk. We’d spend many a long hour debating the nuance of a particular narrative and arguing over the cadence of lines. Acquaintances feared for the survival of our friendship, but we felt grateful to have found someone who shared our fascination with female writers of the past, someone who cared equally about the placement of this comma, the trustworthiness of that source.

With encouragement from readers of SomethingRhymed.com, we became increasingly convinced that the subject of female literary friendship ought to be explored in a full-length book. But over the long haul we clearly couldn’t sustain our time-consuming strategy of sitting side by side at a desk.

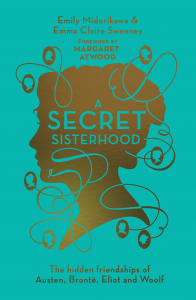

When we came up with a plan for co-writing A Secret Sisterhood: The hidden friendships of Austen, Brontë, Eliot and Woolf, we divided up the research, accumulating stacks of papers that we ferried between our homes. This joint work would lead us to bundles of letters, yellowing with age; neglected wartime diaries; and personal mementoes stored in temperature-controlled rooms.

We journeyed the length and breadth of Britain, deciphering documents in county libraries, and crossed the Atlantic to lay our hands on unpublished correspondence. Our travels took us from the spacious Connecticut summer home of Harriet Beecher Stowe to rented rooms in Bath where Jane Austen endured shrunken circumstances following the death of her father.

This kind of research was not new to us since we had both been working for several years as lecturers. Although we taught at the same university we’d never studied together. And so, spending much of our free time scouring archives, we relished this second stab at studenthood.

But while collaborating on A Secret Sisterhood would bring us much happiness, it would also create new stresses and strains. Leisurely conversations over coffee or glasses of wine were replaced by rushed updates, snatched in library corners, and nights out together sacrificed for evenings writing in our homes, working into the early hours.

But while collaborating on A Secret Sisterhood would bring us much happiness, it would also create new stresses and strains. Leisurely conversations over coffee or glasses of wine were replaced by rushed updates, snatched in library corners, and nights out together sacrificed for evenings writing in our homes, working into the early hours.

We divvied up chapters, assigning half each to work on separately. Once we had composed the first draft, we would send them off to each other to revise. During this intensive drafting period, we were in touch several times every day. But, ironically, we were so immersed in our joint work that we hardly had time to see each other.

Indeed, we became so caught up in the minutia of the email attachments that pinged between us that we failed to discuss much else. Our lives had continued apace – the publication of a debut novel, family illnesses, a new relationship embarked upon – but we scarcely found the time to talk about these important events.

Once we’d completed a full draft, we swiftly found ourselves spending plenty of time together again. At the beginning of the new year, we holed ourselves away for a week to begin working with our editor’s notes. Little did we know it then, but this marked the beginning of several months of spending most days (and more nights than we care to remember) cooped up together in one of our studies.

We’d reward ourselves with a walk in the park once we’d revised a chapter, or a takeaway cappuccino when we’d proofread a section of the bibliography. And during these moments of reprieve, we caught up on the news that had accumulated in each other’s lives.

Back at the desk, we’d return to the task of debating the structure of a paragraph or the credibility of a particular claim. The disagreements became so heated at times that an onlooker might well have assumed we were falling out. But the fiery exchanges never spread from the study, and we quickly learnt to apologise when we went too far.

Gradually we came to a realization. Usually neither of us was right during these arguments; by firing ideas back and forth, we came to new understandings that often incorporated the best of each of our thoughts. Co-writing ultimately helped us to slough off each other’s flaws and benefit from each other’s strengths, an experience that ultimately drew us even closer than we’d been before.

—

ABOUT A SECRET SISTERHOOD

In their first book together, Midorikawa and Sweeney resurrect four literary collaborations, which were sometimes illicit, scandalous and volatile; sometimes supportive, radical or inspiring; but always, until now, tantalisingly consigned to the shadows.

Drawing on letters and diaries, some of which have never been published before, and new documents uncovered during the authors’ research, the creative connections explored here reveal: Jane Austen’s bond with a family servant, the amateur playwright Anne Sharp; how Charlotte Brontë was inspired by the daring feminist Mary Taylor; the transatlantic relationship between George Eliot and the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe; and the underlying erotic charge that lit the friendship of Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield – a pair too often dismissed as bitter foes.

A Secret Sisterhood uncovers the hidden literary friendships of the world’s most respected female authors.

—

Writer friends Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney are the authors of A Secret Sisterhood: The hidden friendships of Austen, Brontë, Eliot and Woolf, which is available to purchase in the UK and to pre-order in the USA. They also co-run SomethingRhymed.com, a website that celebrates female literary friendship. They have written for the likes of the Guardian, the Independent on Sunday and The Times. Emily is a winner of the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize, Emma is author of the award-winning novel Owl Song at Dawn, and they both teach at New York University London.

You can follow them on Twitter via @emilymidorikawa and @emmacsweeney, and Emma has an author page on Facebook.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post