Writing and PTSD: After the Accident

After the Accident

Imagine it’s New Year’s Eve, you’re twenty-one years old, your vehicle is rear-ended by a drunk driver, and your best friend is killed.

Imagine it’s New Year’s Eve, you’re twenty-one years old, your vehicle is rear-ended by a drunk driver, and your best friend is killed.

What do you do when the driver is ticketed for careless driving and is free to live his life?

What do you do when your family pretends the murder never happened?

What do you do when, thirty years later, you buy a house less than two miles from the scene of the accident and experience a panic attack each time you drive through the intersection?

What do you do when you realize you’ve suffered from PTSD your entire adult life?

❖ ❖ ❖

The obvious answer for a writer is to write about the accident.

After the accident, well-wishers tell me I’m the lucky one to have survived. My parents shove me back to college for my final semester. No counseling or therapy is offered. Instead,

I paint a Dead-End sign above a weed-strewn coffin with a dagger piercing a field of flowers. I write hollow poetry. I search tarot cards for answers.

Why me? Why did I survive?

Guilt overpowers me. Does my life hold more value than my friend’s? Is there a higher purpose to her death? Is there such a thing as fate, or are life and death a series of random events?

Time moves on.

My dream of being a writer and college professor is long gone. I’m caught in a liminal space beyond the American dream. My survival tools of superficial relationships and meaningless employment suppress my belief that I was the one who should have died.

I satisfy my creativity through journaling and writing poetry. It’s nonsense no one will read, tucked away in a basement box, waiting for the day I die, when someone might take the time to skim a few pages before shoving it into a dumpster.

I’m not a wife, not a mom. I live alone, moving from place to place, carrying my box of worthless words with me until the box becomes a burden and I toss it.

I long for connection. Female friendships are too difficult. How much do I share? How do I open my heart to someone? What if you, my new friend, are taken from me? What if you, too, realize I was the one who should have died?

Ten years pass. I journal and write more poetry on meaningless topics, never addressing the scar at my core. I turn to counseling and yoga and finally step through the threshold into adulthood. I find a career, a business, a husband, and a home.

I’d like to wrap it up with a happy ending. Yes, I’m happy. But that’s different from a happy ending. The traumas of youth stay with me, fossilized in the layers of my unconscious mind. The zeitgeist now is to tell all. Air your dirty laundry. Proudly wear your abuse and trauma like family heirlooms. But I can’t. What’s the point? I can’t change what happened. I can only change my perspective.

More years pass. I write for the vocational school I own: grant proposals, handbooks, catalogs, curriculum, and advertisements. Once I sell the business, I promise myself I’ll tell my story. For now, I pretend I’m okay. I learned from my family who still pretends nothing happened.

The school sells. I enroll in a liberal arts graduate program. I find my creative spirit. I write essays and participate in online forums and discussions. I’m empowered and promise myself I’ll get to the story soon.

Years pass. With more time for creativity and more years behind me, I turn to memoir, still avoiding the source of my grief.

❖ ❖ ❖

My husband and I buy a house, the home I’ve always wanted. No winding ways in cookie-cutter suburbs but a historic neighborhood complete with friendly neighbors, sidewalks, ancient oaks, and maples.

On the nearby highway, I arrive at the intersection where my friend died. It’s not the first time I’ve been here since that night, but now it’s unavoidable. I shiver. I panic. I have no memory of the impact, only what came next: confusion and an end to youthful innocence.

Years later, another accident occurs at the intersection. A young girl is killed weeks after high school graduation. Who was she? Was she, too, killed by a drunk driver? Her family plants a roadside cross adorned with plastic flowers. Teddy bears, mementos, and a soon-faded photo litter the ground.

Please, may I share the memorial?

Time passes. The cross is overgrown. Has her family moved on? Moved away?

Does anyone remember besides me? My gut clenches each time I pass.

A shared destiny, a shared death.

I’m several miles from the intersection listening to NPR. The guest discusses PTSD, a popularized condition since 9/11 and the Iraq war. She talks about symptoms. She’s speaking to me.

A switch goes on in my brain. I—me—I have PTSD.

Admission is the first step toward healing.

❖ ❖ ❖

I enroll in writing classes and finally turn my focus away from business. I write flash fiction, personal essays, and short memoir pieces. I explore my dark years, my successes, failures, joys, and sorrows. But I never address the accident, the catalyst for all that came next.

In 2018, I participate in an online memoir writing workshop, determined to take on my greatest challenge. I lie awake thinking of an outline, my opening statement, and my goal—an end to PTSD.

With a pounding in my chest, a knot in my stomach, and sweaty palms (I know, I know—melodramatic), I sit at my keyboard the next morning and type a few words. Those few words turn into paragraphs, then pages—not too many so I don’t exceed the prescribed word count. I cry, I shiver, I read and reread the piece. I don’t care about syntax, grammar, or flow. My story, the backdrop of my life, has made it to my computer screen.

I lie awake another night or two, reliving the events and refining my writing. And with an exaggerated lift of my right hand, I hit “send.” That night I sleep soundly and arise, certain I’ve been cured of my affliction.

As a test, the next day I drive through the intersection. The roadside cross still speaks to me, the traffic light still threatens, and any lingering negativity or debris left at the scene still haunts me. But I don’t panic. My gut doesn’t betray me. I am on my way to recovery.

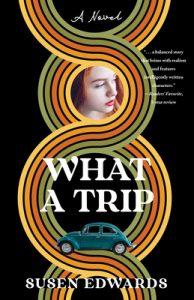

If a short piece holds such power, wouldn’t a full-length memoir have even more healing power? I decide to devote one chapter to my friend and one to me. Memories flow as my fingers find the perfect words for my friend’s Chapter One. After typing Chapter Two my fingers freeze. I need an alter ego. I find her in Fiona, an insecure but beautiful, talented, and intelligent young woman. Other characters pop into Fiona’s life, and soon she takes over as the voice of What a Trip. My memoir morphs into fiction with pieces of personal experience thrown in.

The voice of my friend surfaces prominently throughout the story. I dedicate my first novel to her, Cecelia, and I write this essay in her memory. I’ll never forget the accident. I’ll never drive through the intersection without thinking of her, but now the terror and fear are gone.

—

Susen Edwards is the founder and former director of Somerset School of Massage Therapy, New Jersey’s first state-approved and nationally accredited postsecondary school for massage therapy. During her tenure she was nominated by Merrill Lynch for Inc. Magazine’s Entrepreneur of the Year Award. After the successful sale of the business, she became an administrator at her local community college. She is currently secretary for the board of trustees for her town library and a full-time writer. Her passions are yoga, cooking, reading, and, of course, writing. Susen lives in Central New Jersey with her husband, Bob, and her two fuzzy feline babies, Harold and Maude. She is the author of Doctor Whisper and Nurse Willow, a children’s fantasy. What a Trip is her first adult novel.

WHAT A TRIP

In this fast-paced coming-of-age novel we meet Fiona, an art student at a New Jersey college who is brilliant, beautiful, and struggling to find herself. Through her eyes we relive the turbulent culture of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll, the first draft lottery since World War II, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, the Kent State University shootings, and the harsh realities of war for Americans in their early twenties.

In this fast-paced coming-of-age novel we meet Fiona, an art student at a New Jersey college who is brilliant, beautiful, and struggling to find herself. Through her eyes we relive the turbulent culture of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll, the first draft lottery since World War II, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, the Kent State University shootings, and the harsh realities of war for Americans in their early twenties.

Fiona’s best friend, Melissa, is in a dead-end relationship, pregnant, and going nowhere fast. After Melissa’s abortion, Fiona and Melissa spend a week in Florida, where they are introduced to tarot cards and the anti-war movement. Following this experience, Melissa becomes obsessed with the occult; Fiona, though intrigued, approaches the tarot cautiously, with the voice of her conservative Christian mother screaming in her head.

After Fiona’s return from Florida, she begins dating Reuben–a journalism major and political activist. Reuben decides to move to Canada to avoid the draft and encourages Fiona to accompany him. But is that really what she wants? Caught between her feelings for Reuben and her own aspirations, Fiona struggles to define herself, her artistic career, and her future.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips