Almost

Almost could go either way. A potential—for the negative or positive. The glass is almost full. It’s almost empty. Almost is about just barely, a narrow margin, coming close. A seed that germinates and turns to fruit or flower, or doesn’t. It’s about fate.

If you think about the two words all and most, your odds sound pretty good. But it depends on the way you use it, on what almost happened. He almost missed the plane! Did he barely make it on board and arrive to his sister’s wedding on time, or did he become a passenger on a plane that crashed?

We almost won.

I almost fell in love.

She almost lost her way.

We almost didn’t meet.

I almost laughed during the funeral.

Almost.

The middle grade novel-in-verse I wrote in the traumatic moments and months following 9/11 almost died on the page, on a Word doc on my old dusty laptop, because apparently almost no one in the whole wide world wanted to read it. Almost. More than one agent told me no one wanted to be reminded of the indescribable morning when 19 militants associated with al-Qaeda hijacked airplanes and used them as weapons. There were countless stories of almost from that day—the near misses. We almost toured the towers that morning. He almost didn’t make it out alive. And then there were the reverberations of tragedy—the almost 3,000 people in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania who lost their lives.

My novel tells the story of seventh grader Abbey Wood as she learns her Aunt Rose has gone missing from the World Trade Centers. And in addition to confronting the possibility of her aunt’s death, she must grapple with her father’s imminent deployment to Afghanistan.

Abbey’s story is also my two brothers’ story. Both were called up for active duty in the conflicts following 9/11. My brothers, who flew away from us to Afghanistan and Iraq, with B-positive written on their combat boots—their optimistic blood type. My brothers, who eventually returned safely from those conflicts. I often wonder about the almosts they encountered overseas.

After approximately 90 submissions of my novel to agents, 28 rejections from publishers, one failed relationship with an agent, a bright and shiny new agent, two years of waiting, wondering, doubting, and questioning, I almost gave up on Abbey’s story.

But then, this past year, I almost won a contest, a picture book I’d written received Honorable Mention at a writing conference. And then I published a very small poem in a somewhat big children’s magazine. My MFA had paid off with a four-line poem about hugs that someone’s child could perhaps read in a doctor’s office.

I almost didn’t tell my agent about these minor accomplishments. But I did.

This got her thinking about the novel we almost quit, which led her to put it on the desk of an editor who hadn’t yet seen it. An editor who was a 7th grader, like Abbey in my novel, on 9/11. This editor was living in New York at the time of 9/11. It felt almost like it was meant to be, like serendipity.

I think writing is about almost. You have to see potential in what you’re doing—in your words, your characters, your readers, in life. Why do it otherwise? You have to believe that almost is just one step on the way to something more. And yes, that step can be scary, and you may fall. You likely will. You may even want to give up along the way, like I almost did with a manuscript that is now on its path to becoming a book. A book about 9/11, almost 20 years after 9/11.

How will you know what might have been if you don’t keep putting words onto the page and putting those pages out in to the world? As Emily Dickinson writes in her poem “Almost!”:

Within my reach!

I could have touched!

I might have chanced that way!

So make your almost more certain. Realize it. Write your story. Write the story that breaks your heart or terrifies you or makes you laugh or just comes to you. Don’t almost write. Write.

—

Caroline Brooks DuBois found her poetic voice in the halls of the English Department at Converse College and the University of Bucknell’s Seminar for Young Poets. She received a Master of Fine Arts degree in poetry at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, under the scholarship of Pulitzer Prize winning poet James Tate, among other greats in the poetry world.

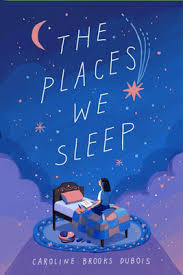

DuBois’s writing infuses poetry and prose and has been published by outlets as varied as Highlights High Five, Southern Poetry Review, and The Journal of the American Medical Association and has been twice honored by the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Her debut middle-grade novel-in-verse, The Places We Sleep, is published by Holiday House and to be released August 2020.

DuBois has taught poetry workshops, writing classes, and English at the middle school, high school, and college levels. In May 2016, she was recognized as a Nashville Blue Ribbon Teacher for her dedication to her students and excellence in teaching adolescents.

DuBois currently lives in Nashville, Tennessee, where she works as an English instructional coach and sometimes co-writes songs for fun with her singer-songwriter husband. She has two teenage children and a dog, Lilli, and she enjoys coaching soccer and generally being outside.

THE PLACES WE SLEEP

A family divided, a country going to war, and a girl desperate to feel at home converge in this stunning novel in verse.

A family divided, a country going to war, and a girl desperate to feel at home converge in this stunning novel in verse.

Selected for Summer/Fall 2020 Indies Introduce List

It’s early September 2001, and twelve-year-old Abbey is the new kid at school. Again.

I worry about people speaking to me / and worry just the same / when they don’t.

Tennessee is her family’s latest stop in a series of moves due to her dad’s work in the Army, but this one might be different. Her school is far from Base, and for the first time, Abbey has found a real friend: loyal, courageous, athletic Camille.

And then it’s September 11. The country is under attack, and Abbey’s “home” looks like it might fall apart. America has changed overnight.

How are we supposed / to keep this up / with the world / crumbling / around us?

Abbey’s body changes, too, while her classmates argue and her family falters. Like everyone around her, she tries to make sense of her own experience as a part of the country’s collective pain. With her mother grieving and her father prepping for active duty, Abbey must learn to cope on her own.

Written in gorgeous narrative verse, Abbey’s coming-of-age story accessibly portrays the military family experience during a tumultuous period in our history. At once personal and universal, it’s a perfect read for fans of sensitive, tender-hearted books like The Thing About Jellyfish.

Category: On Writing