A Hook, Not A Gimmick By April Dávila, author of “142 Ostriches”

A week before I began querying agents for the first time, I was having coffee with a writer friend. I shared with her how nervous and excited I was about those first steps and she asked me what title I’d landed on, as I’d called the book many things over the years. I told her I was going with “Whiskey Glass Theory.”

A week before I began querying agents for the first time, I was having coffee with a writer friend. I shared with her how nervous and excited I was about those first steps and she asked me what title I’d landed on, as I’d called the book many things over the years. I told her I was going with “Whiskey Glass Theory.”

I loved it. It was an artistic, slightly-cryptic nod to the crux of the story, the misguided life philosophies that have kept the story’s fictional family stuck in toxic cycles for generations. My friend was not so sure. “Everyone’s going to call it ‘the ostrich book,’” she said. “That’s your hook. You should embrace it.”

I had considered titles with ostriches, but ultimately rejected them because I didn’t want my title to feel like a gimmick. I worked hard to create a heartfelt story about four generations of women, living in an isolated desert environment, struggling with legacies of abuse and hope against reason. I wanted to respect that. But my friend had called it a hook; a useful marketing term from someone I respected.

So I found myself asking the question: Can you have a hook that isn’t a gimmick?

In my understanding, a gimmick is used simply to get attention, adding little (if anything) to a story. In fact, the word gimmick was originally used to describe a device employed to secretly control gambling machines. In other words, a trick. The negative connotations are easy to understand.

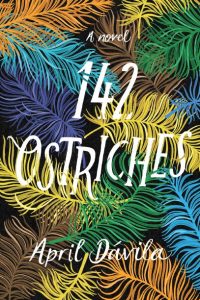

A hook, on the other hand, is the thing that sets your story apart from others. It’s the unique element in your narrative (be it setting, character or plot) that grabs and holds a reader’s attention as they learn about the world you’ve created. A gimmick can masquerade as a hook for a little while, but ultimately it doesn’t deliver. I decided my friend was right. I changed the title to “142 Ostriches” and the decision has informed everything from the book’s cover design to my Twitter feed.

Since then, I’ve enjoyed watching people’s faces when I tell them my title. Some appear intrigued (dare I say – hooked?), while others get that tell-tale squint of the skeptic. But then, as I tell them a little more about my novel, I can almost watch their doubt shift to understanding.

“142 Ostriches” was inspired by my mom’s experiences growing up on a dairy farm in the Sacramento Valley. But I wanted to set my story in the desert. As an ecology major at Scripps College I’d fallen in love with the Mojave’s explosive sunrises, its defensive flora and hardy fauna.

When my mother assured me that no amount of creative license could justify a dairy farm in the Mojave, a fortuitous combination of search terms lead me to the OK Corral Ostrich Ranch, just sixty miles from my home in Los Angeles. I immediately emailed the owner to ask for a tour.

Within minutes of arriving I knew I’d found something special. The birds were so strange, with their prehistoric skin and Lancome eyelashes. The owner of the ranch spoke of them with such affection, even while swatting away their invasive pecks. This was a place for contradictions. The perfect setting for a story about a family torn between love and hate, loyalty and abandonment.

How I came to set my story on an ostrich ranch illustrates the fundamental difference between gimmick and hook. Intention. I didn’t set the book on an ostrich ranch because I thought it would compel people to buy it. If that had been my goal, I might have picked a more lovable animal, something soft and endearing. Chinchillas maybe? Frankly, ostriches are kind of strange. But I loved them for this story. Their hearty constitutions and quirky personalities echoed traits of the people I’ve met in the desert, the characters I wanted to create.

I didn’t even think about marketing my book until that conversation with my friend, a week before I sent out my first query letters. But now that all the revisions are done and I’m in full-blown launch mode, I’m eternally grateful that she pushed me to acknowledge the strong hook in front me.

So when it comes to hooks and gimmicks, my advice is this: write the book you feel compelled to write. When it comes time to put it out into the world, when you have to switch hats and market what you’ve written, consider what sets it apart, what makes it different from the thousands of other books that will come out the same year. It’s a hook, not a gimmick. Embrace it.

—

April Dávila received her undergraduate degree from Scripps College before going on to study writing at USC. She was a resident of the Dorland Mountain Arts Colony in 2017 and attended the Squaw Valley Community of Writers in 2018. In 2019 her short story “Ultra” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. A fourth-generation Californian, she lives in La Cañada Flintridge with her husband and two children. She is a practicing Buddhist, half-hearted gardener, and occasional runner. 142 Ostriches is her first novel.

Book Description or, “142 Ostriches” in 142 Words:

142 Ostriches follows 22-year-old Tallulah Jones, who wants nothing more than to escape her life working on the family’s ostrich ranch in the Mojave Desert. But when her grandmother dies under questionable circumstances, Tallulah finds herself the sole heir of the business just days before the birds mysteriously stop laying eggs.

142 Ostriches follows 22-year-old Tallulah Jones, who wants nothing more than to escape her life working on the family’s ostrich ranch in the Mojave Desert. But when her grandmother dies under questionable circumstances, Tallulah finds herself the sole heir of the business just days before the birds mysteriously stop laying eggs.

Guarding the secret of the suddenly barren birds, Tallulah endeavors to force through a sale of the ranch, a task that is complicated by the arrival of her extended family. Their designs on the property, and deeply rooted dysfunction, threaten Tallulah’s ambitions and eventually her life.

With no options left, Tallulah must pull her head out of the sand and face the 50-year legacy of a family in turmoil: the reality of her grandmother’s almost certain suicide, her mother’s alcoholism, her uncle’s covetous anger, and the 142 ostriches whose lives are in her hands.

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Love the cover- also how you used the ostrich analogy in your book description with the character’s decision to pull her head out of the sand. Best wishes!