A TURING TEST FOR FICTION By Katherine Forbes Riley

When can a man write as a woman? A woman of another culture? A brutally raped woman? When is this acceptable and when does it fail a test society hasn’t explicitly defined, but we still see administered? Moreover, the test itself also changes, for we can all name certain memorable books that passed with flying colors back in their day but would certainly fail in this one.

When can a man write as a woman? A woman of another culture? A brutally raped woman? When is this acceptable and when does it fail a test society hasn’t explicitly defined, but we still see administered? Moreover, the test itself also changes, for we can all name certain memorable books that passed with flying colors back in their day but would certainly fail in this one.

Incidentally, many may not know that Shakespeare’s first hundred or so sonnets were written to a man. I certainly didn’t! Not until recently, when I went searching for an epigraph in a particular sonnet that I’d fallen in love with decades ago. And when I learned this new fact— new to me at least—I thought at first, what a brilliant man. And then, why did I never know this? Also, as I continued reading the sonnets, now with a more universal point of view, how was this kept from me? I scented intentionality in some deep-twisted and conspiracy- theoretical way.

To be clear, just like the test itself, its results often aren’t clear either. There tends to be two poles: one that finds the proctored book perfectly acceptable and another that finds it utterly and disgustingly disrespectful. The rest of us are spread out in between, perhaps in the shape of a bell curve. And we may not keep our positions fixed either.

The purpose of this piece is not to show how a fictional text might pass this test, but rather to suggest the possibility of reframing it, with the help of a computer science theory that the wide- mouth bell of us have all been exposed to, and that many, at least in our imaginations, know intimately.

Before becoming a creative writer, I obtained my PhD in computational linguistics, which is a field that combines the studies of linguistics and computer science with the goal of building computers that interact with humans naturally. I worked on a project for a decade that taught a computer tutor to recognize student emotions and react naturally. Never mind that he couldn’t “think” (now why did I say “he” when our speech synthesizer used a variety of genders and accents as its voices?). The question that drove us, and ultimately beat us, was: what does it mean for him/her/it to “recognize” and “react naturally”? Not even all human tutors do this in the same way. Some teachers I’ve had were highly perceptive of my emotional state, and others, not at all. And there’s no clear line, at least in my mind, between which of them was a better teacher either…but I digress.

This question more generally has captivated computer scientists for a century. Because even the concept proved so difficult to define, Alan Turning (a gay man, incidentally, disgustingly persecuted for it, as Benedict Cumberbach – not a gay man – so brilliantly portrayed in The Imitation Game), proposed a behavioral test: a human tester interacts with two other individuals, all unseen. One of them is human, the other computer, and the tester must decide

which is which, based entirely on the unseen behavior they exhibit. Passing the test, therefore, requires the computer to behave indistinguishably from the human. Turing, it should be noted, didn’t show how to pass the test either.

Nevertheless, it is a question – a test – that by now has captivated many of us, as recently and most gorgeously exemplified by the young Alicia Vikander in Ex Machina (or pick your own favorite robot character from the many movies in this vein). To a computational linguist, the topics covered in that movie were pretty basic, and the leap from them to the perfect form Alicia portrayed was pretty large. But the point—the fascination—the question—remains.

And I’d like to argue that it’s the same (or a behaviorally indistinguishable) question to the one we’re all asking as readers and writers of the fictional texts we read. When we ask, is this fiction authentic enough? We’re really asking, does it pass our authenticity test? Moreover, and far more interestingly, viewing the test through this scientific lens also illuminates how the edges are incomplete. As explanation through example, and still without naming names, consider the recent example of a white male writer (sorry, not sorry) who wrote about another culture as if he were a member and even used a culturally appropriated pseudonym to boot. He fooled one audience, passed its Turing Test. But I argue that the test was incomplete. Did he fool the culture(s) he wrote about? Did he pass their Turing Tests?

A Turing Test, it must finally be noted, lacks a moral judgment. It doesn’t, for example, address associated appropriation questions such as, is it right for a fictional text to pass another culture’s Turing Test? Should it be given rights if it passes that test? It seems to me that this is part of Turing’s brilliance. I also personally think it’s possible—although I may be positioned at a polar extreme in this—that the passing of a culture’s test might itself render the associated appropriation questions moot. Simultaneously, I think it would be highly unlikely for most texts to pass another culture’s test. In any event, I believe—hope—that the texts and the tests and the moral questions that accompany them will all continue to evolve side by side with a concept of humanity in which every culture is given space to freely coexist and blur and blend.

—

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/kforbesriley

“Teeming with lush imagery and mystical settings, and brimming with alluring magical realism, Riley’s tale is a beguiling journey of discovery and recovery.” — Booklist

“Teeming with lush imagery and mystical settings, and brimming with alluring magical realism, Riley’s tale is a beguiling journey of discovery and recovery.” — Booklist

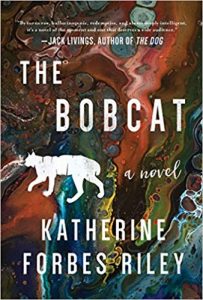

Haunting and lyrical, The Bobcat is Katherine Forbes Riley’s magical debut novel in which Laurelie, a young art student who suffers in the aftermath of a sexual assault, has grown progressively more isolated and fearful. She transfers from her busy city university to a small college in rural Vermont, where she retreats into her vivid imagination, experiencing the world through her art. Most comfortable in the company of the child for whom she babysits, and most at ease in the woods, Laurelie has shunned any connection with her peers.

One day, while exploring the woods, she and her young charge encounter an injured pregnant bobcat – and the hiker who has been following it for hundreds of miles. In the hiker and his feline companion Laurelie recognizes someone as reclusive and wary as herself. The hiker, too, finds human companionship painful to endure, yet he is drawn to wounded Laurelie the way he is drawn to the bobcat. As Laurelie moves toward recovery and reconnection she also finds her voice as an artist, and a sense of purpose, maybe even a future, comes into sight. Then the child goes missing in the woods, threatening the bobcat, the hiker, and the fragile peace Laurelie has constructed.

With the hypnotic intensity of Emily Fridlund’s The History of Wolves and Fiona McFarlane’s The Night Guest, Riley has created a mesmerizing love story, in lush, gorgeous prose, that examines art, science, and the magic of human chemistry.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips