All In

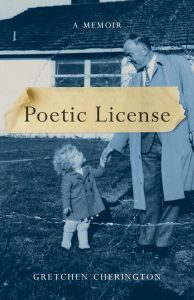

My first book, Poetic License-A Memoir, was released in August. Publication day culminated a twenty-year quest to figure out who my father was to me over our long and complex relationship and to better define myself outside the shadow of his literary fame. The manuscript had been threaded through two full decades of my life, alongside marriage, family, and career. As the spiritual teacher Mark Nepo writes in Drinking from the River of Light, we must be patient—exhaustive even—to do our essential work.

My first book, Poetic License-A Memoir, was released in August. Publication day culminated a twenty-year quest to figure out who my father was to me over our long and complex relationship and to better define myself outside the shadow of his literary fame. The manuscript had been threaded through two full decades of my life, alongside marriage, family, and career. As the spiritual teacher Mark Nepo writes in Drinking from the River of Light, we must be patient—exhaustive even—to do our essential work.

Through that twenty years, I learned to create scenes, became expert at dialogue, found a structure to hold my story, and came to my true voice. I’d signed with a terrific press and had a publicity team eager to get started.

So, why was I so ambivalent on the eve of publication, a moment I’d long dreamed of, but often felt might never happen? Why was I so hesitant to become “an author” when ambivalence had never been my MO?

My vacillation came from the story itself. My father’s prominence as a U.S. poet laureate had cemented in my consciousness one view of how an author can be in the public sphere. He loved his fame—the attention, being sought out for advice, surrounding himself in a constant swirl of fans.

Lucky for him, that version of authorship followed him through a successful, seventy-year literary career. But for years I’d been chafing at his me-me-me. My father had no ambivalence about the limelight. Unfiltered, as we might call him today, his tribe of editors and publishers enabled not only his greatest writing, but a lot of poems that weren’t very good.

When, in the late 1950s, Dad asked his friend Robert Penn Warren for a blurb for his upcoming book, Warren replied, I’ll be delighted to express my deep and abiding partiality for some of your poems. No matter the critique from his friends or family he wasn’t one to rework again and again what his muse had delivered. The idea of being exhaustive, something the poet Donald Hall told me was his own MO, was not my father’s.

After my mother died in 1994 and through my father’s death in 2005, I was cast in the role of Dad’s surrogate. As he passed through his nineties and into his 102nd year, I was the go-to person for anthologists, editors, and the press for their copyright questions, their permissions to use poems, or their need for a sound bite about a beloved writer friend of Dad’s who had just died.

At the same time, I was researching and writing down the bones of Poetic License, coming to terms with my relationship with my father and no longer willing to entirely void my experience of him for the one preferred by his public. It became harder and harder to express the family line of praise when reporters tilted their microphones at me. There was something inherently unappealing to me about the vanity of celebrities.

I’d been advising CEOs on how to change their companies and themselves through my professional career and I was surprised at times to hear of their ambivalence about being at the top—in quiet rooms, they accepted the power they had but noted the high responsibility that came with it.

If I asked them—they were mostly men in the early days—the kind of question Mary Oliver poses in her poem “The Summer Day” (Tell me what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?), replacing “precious” with “privileged”, the best of them knew that privilege came not just from their own hard work but from the many who’d helped them along the way, plus a good bit of luck and timing.

Some could see the privilege came by virtue of birth, race, or gender. What they wanted, though, the best of them, was to be of service, to make life better for the people around them, to improve the world. I saw in them a different example of fame, one less focused on self and more focused on other.

Walking along a wooded trail near my home the other day, now nearly two months post publication, I found myself thinking about these two versions of fame. Fall asters littered the edge of a shallow stream and birch trees were turning gold. A merry band of ravens laughed overhead, as if themselves exemplifying for me, a version of “me-me-me”.

With clients, I’d been privileged to share my voice in private conference rooms and corner suites. Being “an author” was taking me into the much more public square, introducing me to a new community of readers and writers from around the world. Getting the book out took a lot of hard work, along with the help of countless people, and some luck and timing.

I’ve noticed the fellow writers with great generosity to newcomers; the life stories shared with avid readers; the desire to make this world a better place; the aspiration to become ever more fully human. I have so much to learn. Holding a dose of discomfort in the necessary self-promotion of being an author, the privilege is clear and I’m all in.

—

Gretchen Eberhart Cherington is the author of POETIC LICENSE: A Memoir, one woman’s story of speaking truth in a world where, too often, men still call the shots. She grew up in a household that—thanks to her Pulitzer Prize–winning father, the poet Richard Eberhart—was populated by many of the most revered poets and writers of the twentieth century, from Robert Frost to James Dickey. She’s spent her adult life advising top executives in changing their companies and themselves.

Her essays have been published in Crack The Spine, Bloodroot Literary Magazine, and Yankee Magazine, among other journals and newspapers, and her essay “Maine Roustabout” was nominated for a 2012 Pushcart Prize. Cherington is a leader in her community and has served on twenty boards. Passionate about her family and friends, she most enjoys spending time with them at home or in wild places around the world. Learn more at https://www.gretchencherington.com

POETIC LICENSE: A Memoir

At age forty, with two growing children and a new consulting company she’d recently founded, Gretchen Cherington, daughter of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Richard Eberhart, faced a dilemma: Should she protect her parents’ well-crafted family myths while continuing to silence her own voice?

At age forty, with two growing children and a new consulting company she’d recently founded, Gretchen Cherington, daughter of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Richard Eberhart, faced a dilemma: Should she protect her parents’ well-crafted family myths while continuing to silence her own voice?

Or was it time to challenge those myths and speak her truth–even the unbearable truth that her generous and kind father had sexually violated her? In this powerful memoir, aided by her father’s extensive archives at Dartmouth College and interviews with some of her father’s best friends, Cherington candidly and courageously retraces her past to make sense of her father and herself.

From the women’s movement of the ’60s and the back-to-the-land movement of the ’70s to Cherington’s consulting work through three decades with powerful executives to her eventual decision to speak publicly in the formative months of #MeToo, Poetic License is one woman’s story of speaking truth in a world where, too often, men still call the shots..

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing