An Author and Her Editor Haggle Over Details

An Author and Her Editor Haggle Over Details: Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood and Travis Snyder

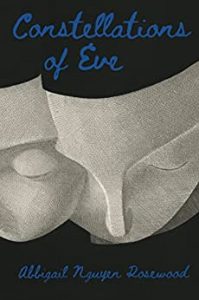

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood’s Constellations of Eve as a Unique Editorial Experiment

In her new novel Constellations of Eve, Abbigail Rosewood offers three iterations of one love story, each beginning over with a few changed variables. These seemingly small augmentations drastically alter the lives of her main three characters—Eve, Pari, and Liam. The novel is a study in the little acts of randomness from the universe and the twisting relationships that follow after. I have thought a great deal about it because, well, I was Abbigail’s editor for Constellations of Eve.

In her new novel Constellations of Eve, Abbigail Rosewood offers three iterations of one love story, each beginning over with a few changed variables. These seemingly small augmentations drastically alter the lives of her main three characters—Eve, Pari, and Liam. The novel is a study in the little acts of randomness from the universe and the twisting relationships that follow after. I have thought a great deal about it because, well, I was Abbigail’s editor for Constellations of Eve.

The cause-and-effect structure of the novel lent itself to focused and granular editing. Abbigail is sparing and exact with her details. A suggested word deletion could run up a dozen responses in Microsoft track changes, spilling over into text messages or a too-long email. As sometimes happens between writers and editors (though not always), we became friends.

While I don’t know if it necessarily makes for better or worse editing, our ongoing conversation lent context to what made the book work, and it unspooled our general thoughts on reading, writing, and being. Over our last holiday break, we formalized our iterative back and forth over email, speaking of the big things that lurked behind our editing this novel together.

TRAVIS SNYDER: Abbi, I think It’s worth talking a little bit about artist-as-character. It’s different, to my mind, from the varying shades of autofiction floating around the contemporary literary market. There are a lot of books that revolve around specialized depictions of the literature business. That sort of thing is interesting to readers like you and I (it’s our world, after all), but you didn’t write Constellations for that reader. And still, you made Eve an artist. I wonder what draws you to write about art-making, and I wonder if you give yourself boundaries around that sort of topic?

TRAVIS SNYDER: Abbi, I think It’s worth talking a little bit about artist-as-character. It’s different, to my mind, from the varying shades of autofiction floating around the contemporary literary market. There are a lot of books that revolve around specialized depictions of the literature business. That sort of thing is interesting to readers like you and I (it’s our world, after all), but you didn’t write Constellations for that reader. And still, you made Eve an artist. I wonder what draws you to write about art-making, and I wonder if you give yourself boundaries around that sort of topic?

ABBIGAIL ROSEWOOD: When I first started to take writing more seriously, I told myself that I would never write about writing or feature a protagonist who is a writer. Perhaps it stemmed from a combination of insecurity, who would be interested in a writer, and my own lack of interest in what it meant to be a writer. Yet writing is art-making, and I was infinitely captivated by this topic. Eve is a painter and a sculptor. Because I’m also a visual thinker, her character gave me access to explore ideas I already intuited, but also opened up new modes of thoughts. She is both familiar and strange—this is the space in fiction that I’m invested in. I don’t only want to reach for what I know, but I also tend not to write about things of which I have zero understanding.

As I become a more experienced writer and reader, I find myself gravitating more and more towards stories that do depict writers and writing life, whereas I used to think they were somewhat uninspired. I have a totally different outlook now—I wonder if those stories more readily collapse the wall between fiction and life. What I previously misunderstood as lazy, is actually courageous.

I texted you about Knausgaard recently. The My Struggles series changed my perspective, and showed me that just by the virtue of focusing our attention on the mundane, like coffee, household items—in the sixth book, Knausgaard wrote over a page where he just listed objects in his apartment—they are transformed through language, the same way a painting of a still life of an apple, a pitcher of milk, or a leaf of newspaper are transformed simply because the artist decided to contemplate them. I’m curious about anything that connotes creation, pregnancy and birth, architecture, art. I’m playing around with a short story now about an architect who dreams of designing toward invisibility, using materials that under the right lighting and conditions, look as though they weren’t there at all. It’s a challenge because I don’t know much about architecture, but I do have some idea about bringing something into being. My boundary is probably that I still haven’t directly written about being a writer. Despite seeing how effectively this type of autofiction has been done, I still can’t convince myself to sit with a sentence that is about someone sitting with a sentence.

Constellations of Eve replays the same story three different times; in each telling a variable changes, to some significant effect. Different characters die or fall in love based on some slight tweak in the details. Is this indicative of the way you view life in general? It strikes me a bit like algebra (the most advanced math I could wrap my head around)–do you find yourself hypothetically rearranging little margins in your mind and wondering if life would be different if…?

It’s funny you mention algebra—I was never good at math, but I preferred it over geometry or statistics, perhaps because the conditionals like if x then y in algebra are inherently imaginative, or at least open to rearrangement. Other people have played around with algebraic-like equations: if a loves b; and b loves c; then a loves c. Of course, that may be logically true, but humans aren’t made of pure logic.

In my own life, I do really enjoy contemplating the what-ifs. It’s easy for me to imagine ending one life and beginning another. I can embody the feelings of what it might be like to go into a store, and not buy milk this time, but rob the register, or have a temper tantrum so profound in the international aisle that I’d be taken to an institute. Another less extreme example I do often is picturing myself living elsewhere. In my head, I’m always moving. Maybe that’s because moving is an easy way to drastically change your life?

You and I have both been up to a good deal of change in recent years. We’ve both moved from the city to the country (you a bit more dramatically so than me). Our partners have each changed career and life paths. Both of us have far flung families. Sometimes I feel very cosmopolitan about this. Sometimes I feel totally unmoored. I wonder if you feel some sort of artistic sensibility resonating from this placelessness? In myself, I sometimes worry about the loss of the local feelings I associate with my more rooted childhood.

The local feeling is something I’ve been searching for ever since I left Vietnam, and for better or worse, I’ve not found it again. When I was still in the city, I tried to artificially create familiarity by getting to know the bodega owner in my neighborhood. I once asked him to order me these sugar free cookies, so he now knew a small but specific detail about me. I also got to know one doorman in this building across the park whose work hours coincided with when I walked my dog. One day, I bursted into tears in front of him—once that boundary or sense of otherness is dissolved, all that’s left is human. From then on, he was able to share intimate details about his family, his children, topics we wouldn’t have gotten into otherwise.

I don’t ever feel like I can get to know a place. My husband often teasingly recalls that I walked past The Vatican without noticing it. In many ways, I situate myself with human sign posts, where I have some sort of emotional resonance, no matter how fleeting, but I rarely remember landmarks or street names. I think that sense of placelessness saturates all my writing. You were the first to describe my novel as a fable, and it was such a relief for it to be accurately named. You suggested that I remove all specific names of cities, as beside the names there was nothing else that signal groundedness in the novel. All of the sudden, I felt like I had permission to enter a more surreal space, which is a space I’ve always been more comfortable with and more convinced by.

I want revisit an editorial moment from July. We had been in the weeds for a few months, and then suddenly the manuscript was done. We both felt it, I think. Given how the book invites lots of speculation and tweaking and hypothetical universes, how could you tell it was finished? We could have edited it forever, I think!

Our editing process was pure joy for me. You interacted with my work with such generosity, grace, candidness, sensitivity, and care (and a good dose of humor) as though it was your own, so yes the conversations could have continued indefinitely. In a way, that’s the kind of experience I hope the reader will get from the novel—to hold in their mind several possibilities for these characters beyond the page, but also for themselves. I’ve always thought that working on the same book for five, ten, twenty years—after a certain degree of polish—isn’t going to make the book better or worse. Just different. Like with a furnished room, I can add a vase of flowers, or a candle, or scribble something on the wall, and I can go on doing this for the rest of my life, but I don’t think I want to do that.

I approach all my projects in the same manner. It’s as if whatever demons I’ve been wrestling with, the emotions that ignited the project have been resolved. Publishing also requires that I can’t be a perfectionist. Maybe it says something about me that I’m okay with the seams showing. When I’m immersed in a project, it happily consumes everything. I could care less about meeting a friend because my work fulfills all my needs. So I guess I know something is done when I would rather stay in bed and sleep, or when another feeling takes hold, which is the beginning of a new project if I’m lucky. Otherwise, I don’t end things on purpose because I’m afraid of the abyss that follows. I’m usually a wreck in between projects.

The temptation is to think of the book as a philosophical love story. Honestly, that’s probably what I put into the descriptive copy and marketing material. Which was probably the right notion. But, I think the threads that have stuck with me most from Constellations have more to do with friendship than romance. Friendship is so much more open-ended. It can be erotic; it can be nausea-enducing; it can be embarrassing. A story about friendship can end up anywhere, while most romantic plots come down to “break up or stay together?” The tension between Pari and Eve drives a lot of the conflict. Can you talk about what it was like exploring the bandwidth of friendship?

Friendship is such a fertile territory for fiction. There are breakups in friendship too, but they’re perhaps even harder to execute or handle than romantic relationships. Some friendships flourish with romantic-like expectations and entanglements, while others disintegrate. When I was younger, my notion of friendship was a lot different, more traditionally Romantic. The way my highschool friends and I wrote to each other daily, notes folded into origami animals, talked for eight hours on the phone from night till dawn, was as you said, “nausea-enducing,” but it was also enthralling, intimate, powerful. As a teenager, I was open to these kinds of connections, but now I simply don’t have the bandwidth for such all-consuming friendships anymore.

There is something very child-like about the idea of a best friend, innocent and pure, that I miss. With Pari and Eve, I was trying to explore how two adults might succumb to very naive notions of friendships out of necessity, of loneliness, to their detriment. In some ways, I wonder if their friendship might have found healthier expressions if they were girls, which might make it more acceptable to be two sides of the same coin, or a thing and its shadow, but as adults, they’re supposed to separate, form their own identity, and there is a cost for not quite managing to do so. Pari and Eve as happy teenagers! That’s one variation I’ve not written.

This is the part of our conversation where we talk about Sally Rooney. I just finished Beautiful World. I am going to text you off the record so that we can dish, but something I really enjoyed about the novel was the really unfussy narrative distance. Sometimes we’d be tucked neatly into one character’s thoughts, and then in the same scene we’d somehow be with another person learning their reactions. For most of the book there isn’t a single grounding perspective. Do you think any of the main characters of Constellations serve as a north star for the reader? Eve is the title character. Is she the protagonist?

I love your use of the words north star, which I think might be the most accurate description of Eve, a point to orient the other characters around. In some ways, Eve is secondary to the reincarnations of the stories, which feature three recurring characters. In my mind, Liam and Pari are protagonists too. And yet, I chose Eve as the title because I believe the stories are filtered through her—her intense wish to begin again, to make things right is the catalyst through which the story is born and reborn.

I look forward to properly dish about our opinions over text!

Over the latest winter break, I did something I don’t often do. I reread my favorite book (doesn’t matter, but it’s Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose). Rereading is different from reading for me–a more academic exercise because I’m noticing details more precisely. I’ll start to develop some sense of meaning. Your book has rereading built into it, because the story starts over three times. That makes it more like writing. Beginning again, revising, chasing down frustrated endings. We should leave off this conversation somewhere, and it might as well be here: what’s the difference between reading and writing for you?

I love this question so much! As a writer, I’m always anxious to read the next book, discover the next author, learn another way to tell a story—it begins to feel like a compulsion. I think the mark of maturity as a reader is the exercise of rereading. I have to practice slowing down, sitting with a work for a long time, returning to an old favorite read and finding in it something new. The Light and The Dark by Mikhail Shishkin is one I’ve read and reread. Poetry also has rereading built in—I tend to reread a poem immediately twice, three, four times, right after I’ve just encountered it. I might be lucky (or unlucky?) in the sense that I rarely read critically, even if it’s a second read. Often, the more I admire a book, the more the technical and craft elements dissolve: I am just there. In the world the author has created. This approach also extends to how I write, especially with the first and second draft—I’m not conscious of what I’m doing—basically, I’m not crafting. When I’m feeling out the beginning of a new story, it’s purely intuitive. Editing is more craft-focused. And I don’t truly edit as a “professional” until I’m already at draft five or six—this is when I might look for reverberations, connecting images, themes, feelings.

When I read, as I highlight or underline ideas, I get inspired to write, but it’s not necessarily the other way around. When I write fiction, I don’t feel called to suddenly read a book. In that sense, for me writing is more immersive, more total. In almost all other life activities, something kicks me back into the world of fiction—an overheard phrase, a glimpse of something strange, a sound. My brain doesn’t want to stop creating, expanding, embellishing—this might be how I relate to the world. Sadly, I’m rarely at one with the present, with life. I’m at one when I write.

—

About the Author:

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood was born in Vietnam, where she lived until the age of twelve. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University and lives in Brooklyn, New York. Her short fiction and essays can be found at Electric Lit, LitHub, Catapult, The Southampton Review, The Brooklyn Review, Columbia Journal, and The Adroit Journal, among others. In 2019, her hybrid writing was featured in a multimedia art and poetry exhibit at Eccles Gallery. Her fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best American Short Story 2020. Her debut novel If I Had Two Lives won first place in the Writers Workshop of Asheville Literary Fiction contest. Excerpts from Constellations of Eve were finalists in the 49th New Millenium Writing Award, and the Sunspot Culmination Award. She is the founder of Neon Door, a forthcoming immersive literary exhibit.

Travis Snyder is the Acquisitions Editor at TTUP. He acquires both scholarly and trade titles. He also manages permissions as well as the internship and graduate assistantship programs. He received a PhD in English from Baylor University, specializing in 20th Century American Literature and Postmodern Literary Theory. He has taught at Trinity University and the University of Texas – San Antonio.

THE CONSTELLATIONS OF EVE

Eve is a reluctant mother; Eve is a famous phenomenon; Eve is a quiet country teacher. Liam is a successful artist; Liam is a scheming husband; Liam is a gentle partner. Pari is a leading scientific researcher; Pari is a recognized model; Pari is a picture of declining mental states.

Eve is a reluctant mother; Eve is a famous phenomenon; Eve is a quiet country teacher. Liam is a successful artist; Liam is a scheming husband; Liam is a gentle partner. Pari is a leading scientific researcher; Pari is a recognized model; Pari is a picture of declining mental states.

Constellations of Eve weaves together three deviations of one love story. In each variation, the narrative changes slightly, with life-altering impacts. Against a backdrop of difficult people finding their place in a constantly shifting universe, the novel manipulates the variables leading to their fraught romantic entanglements, tearing through a host of lifetimes in search of the one in which all the brightest stars align.

In this philosophical fable of art and fate, Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood paints a world that floats above our own and contours the infinitesimal moments that shape who we love, over whom we obsess, and how we decide what to live for.

Each reality allows Eve another chance at finding her true destiny and personal and professional fulfilment—but can she get it right? Is there even such a thing as right? Constellations of Eve wrestles with the most intimate betrayals and the staggering personal costs of stifling artistic ambition, pursuing it to the exclusion of family, or letting it disperse in favor of an all-consuming love.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips