An Author’s Search for Place from Mali to Italy

‘You crawl over. You are in Hong Kong. Outside, everything is fumy with light.’

‘You crawl over. You are in Hong Kong. Outside, everything is fumy with light.’

From an early age I knew I would leave my country. Like many authors, I was bookish and removed, and a childhood tragedy made me determined to leave pain behind and head to Europe. At 21 I was a skinny shoplifter walking the streets of Paris, job-searching once my study and my money ran out.

Growing up, I had been as fascinated by Turgenev’s Russia as I was by Patrick White’s inland Australian deserts, by Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and the Indonesia of Christopher Koch’s The Year of Living Dangerously. I knew I would write. I’d thought I would end up in South-East Asia as a political journalist, but life took me much further afield.

‘Inside the church there is a painted, beckoning statue of the young woman whose short life ended in torture on these shores. Sainte Julie is the patron saint of the island.’

The Paris I learned to love was tough and gritty. Though my area is now gentrified, I lived in a risky neighbourhood whose characters I learned by heart. Ivorian ladies in the square, sandals and printed dresses in winter, struggling designers in ill-lit studios, Vietnamese from the traiteurs, drug dealers, working class French rooted in the area. I wrote my first stories in my bohemian employers’ flat above a sweatshop. I went to posh parties in apartments along the river, I became an afternoon film buff. I would lie on the library floor at the Pompidou Centre, long before security checks and extremist gunsmen. I breathed books.

Later, love took me to Italy where I delved into history and art. I wasn’t writing then, but absorbing and learning a language. And because Italy has been written about with such reverence, I was convinced I would never find an original way to produce a meaningful story without invoking clichéd visions of the Mediterranean. Stories set in Italy would come much, much later. There were other writers – the great Shirley Hazzard – whose grasp of the land was much more refined than mine. And also, the writer in exile often looks backward for material, rather than at the surroundings he or she gazes through.

Years after, when my command of the language was stronger, I would work on translations about the First World War, and I discovered the stunning Dolomites: these would be my entry points for writing about Italy.

‘Where his father had been a boy there was a brutal, scarred riverbed Renzo and Monique had roved during their school holidays, hunting for gun cartridges or buttons from the young men blown apart by mortars at the end of the Great War.’

I also spent long, formative stretches in East and West Africa. There I learned to go slower in the heat, to accomplish less in a day, sometimes finding myself in extreme situations that required calm or resolve. I lived in Ghana for nine years and travelled extensively, never ceasing to be amazed by the adaptability of people, the strength and forbearing of women, the ruins of colonialism, the endless music and insane traffic. These years gave me riches for my work, raising many questions along the way. Am I allowed to use the voice of a pregnant Ghanaian woman? Or a South African advertising executive? Or an African migrant hit on his bicycle in Italy? These are some of the storylines I tackled in my collection, hoping to grant authenticity to these characters.

‘The jeep drifted down to the coast, tall grass and stunted trees whipping past. At the city edge there was a roadblock where a group of soldiers sprawled under a broad tree. They were thrown back on benches, khaki trousers tucked into polished boots, slick berets on shaven heads, hands holding rifles.’

Again, it’s the issue of avoiding cliché – writing about West Africa while trying to shift the common view of the continent as being poor, deprived and exotic. And as with all writing, getting into your character’s head, providing a purpose to the reader for the creation of your story, and combining this awareness and responsibility with the magic of recounting a memorable tale. This is especially important to me, as most of my European and African characters in my many stories come from an experience that is not my own, and thus must be represented with as much exactness as I can muster, without stealing and flaunting – I believe this is a writer’s task.

‘The land is flat and soundless with her history manifest in adobe mosques crumbling along the bloodied slave routes, and painted Boulangerie signs in villages where commendable baguettes are sold. The road is a silver spear. Between the messy, unscripted towns there are baobabs.’

Do I have a favourite location for my stories? The boulevards of Paris or the chasms of the Dolomites? Or the unruliness of Bamako’s dusty streets, or Hong Kong’s clustered high-rises? No, not really. I think that as with all short story writers, each piece is a universe that must be unwaveringly conveyed to the reader. And as each story comes together in a different way – with variations in pace and tension – my main concern is the effective conception of characters, and making sure the drive of the story is in place. That is not to say that location is irrelevant! For me, location is like a character – it must be razor-sharp, redolent. The reader must be enchanted and enriched.

‘Cam remembers Gerard’s phone call when he was shattered in Rome after the breakup. The ferry trip from Naples. He sees the house that belonged to someone in Gerard’s family. The building’s solitary prominence on the hillside as you walked up from the bay. The volcano looming behind, an immortal trembling.’

—

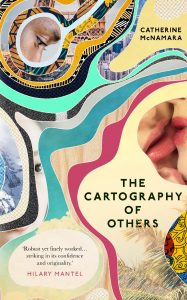

Catherine McNamara grew up in Sydney, ran away to Paris at 21, and ended up in Ghana running a bar. Her collection The Cartography of Others is published by Unbound UK and available online through Amazon, Hive and Gardners. Catherine lives in Italy.

Facebook: Catherine McNamara

Twitter: @catinitaly

About THE CARTOGRAPHY OF OTHERS

The Cartography of Others is a collection of short stories that explores the geography of the body and the migration of the heart

The Cartography of Others is a collection of short stories that explores the geography of the body and the migration of the heart

‘strongly atmospheric from the first sentence’ Hilary Mantel on ‘The Wild Beasts of the Earth Will Adore Him’ (What Lies Beneath, Kingston University Press)

Category: On Writing