Art Taught Me How to Read

Just lately I’ve tried reading novels the way I might visit an art exhibit. When I visit an art exhibit I have no need to make steady progress. I expect to look at a thing from all angles, up close and far away. I spend more time in front of things that draw me in. I might go back again before I leave, just to experience them one more time. And when I go home, for a while at least, it feels as if everything–the sidewalk, the cars and buses, my own hand–is something I am seeing in a new way.

Just lately I’ve tried reading novels the way I might visit an art exhibit. When I visit an art exhibit I have no need to make steady progress. I expect to look at a thing from all angles, up close and far away. I spend more time in front of things that draw me in. I might go back again before I leave, just to experience them one more time. And when I go home, for a while at least, it feels as if everything–the sidewalk, the cars and buses, my own hand–is something I am seeing in a new way.

In contrast I typically read a novel as if I’m on a steady hike. No lingering or backtracking allowed: getting to the end in the most efficient way possible was my implicit goal. If I don’t like where the novel appears to be going I get impatient. I’m constantly looking for reasons to put a book down when there are so many others to be read.

I started to wonder if I’d enjoy reading more if I allowed myself the freedom to read books the way I look at art: without a destination in mind, and without judgment.

I decided to try it.

The first novel I read this way was Frontier by Can Xue. It turned out to be a lucky choice because the novel is anything but linear. I could open Frontier at a random page and it felt like just as reasonable a place to start as any other. I read Frontier in random chunks, a paragraph or two at a time, and I also read it the other way, from left to right and beginning to end, and it took me weeks before I felt ready to leave it, and it didn’t matter to me how long it took, because something contemplative and delightful happened to me as I read and I didn’t want it to be over.

The first novel I read this way was Frontier by Can Xue. It turned out to be a lucky choice because the novel is anything but linear. I could open Frontier at a random page and it felt like just as reasonable a place to start as any other. I read Frontier in random chunks, a paragraph or two at a time, and I also read it the other way, from left to right and beginning to end, and it took me weeks before I felt ready to leave it, and it didn’t matter to me how long it took, because something contemplative and delightful happened to me as I read and I didn’t want it to be over.

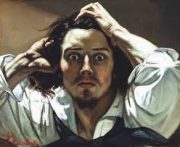

When I was done the novel made sense to me beautifully, especially if I thought of it as a Rothko painting, because at first the novel seemed to have just one color to it, but the longer I stared at it, the more I saw how many colors there really were.

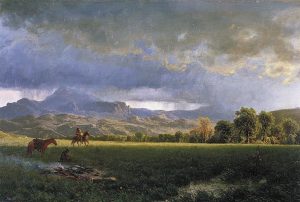

Later I read In the Distance by Hernan Diaz. I resisted everything about it in the beginning. I though this novel was impossible to believe in. And then I gave up trying to make the book conform to my old way of reading, when I was full of purpose and expectation.

Later I read In the Distance by Hernan Diaz. I resisted everything about it in the beginning. I though this novel was impossible to believe in. And then I gave up trying to make the book conform to my old way of reading, when I was full of purpose and expectation.

I tried instead to read the novel as if I were looking at an unexpected painting on a wall, artist unknown. In such a situation, I would offer the artist more courtesy, and more patience. And the next thing I knew as I read Hernan Diaz’s novel I was inside a scene of such great beauty–even though it was about a man cutting his beloved burro open in a futile attempt to save its life–that I thought, for a while at least, that this book was the best thing I had ever read. Art will do that to you.

I began to read every novel with the meandering curiosity of a stroll through a gallery, rather than with the critical efficient purposefulness I had usually read. I tried doubling back as I read, just as I might double back to see a favorite painting in a gallery. Sometimes I read a chapter over completely, either because I liked it, or because it confused me. I gave myself permission to look harder, and to spend more time in one place, rather than trudging gamely toward the end. Or to start over entirely.

I began to read every novel with the meandering curiosity of a stroll through a gallery, rather than with the critical efficient purposefulness I had usually read. I tried doubling back as I read, just as I might double back to see a favorite painting in a gallery. Sometimes I read a chapter over completely, either because I liked it, or because it confused me. I gave myself permission to look harder, and to spend more time in one place, rather than trudging gamely toward the end. Or to start over entirely.

I read Radiant Terminus by Antoine Volodine this way and I discovered the book had a Jackson Pollock-like, patterned randomness.

I re-read Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko, and decided that reading it was something like looking at…

I re-read Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko, and decided that reading it was something like looking at…

…a Joan Miró,

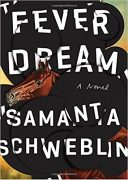

…and after that I read Fever Dream by Samantha Shweblin, a book that once might have annoyed me with its unfinished vague edges…

…and after that I read Fever Dream by Samantha Shweblin, a book that once might have annoyed me with its unfinished vague edges…

…until I thought of it as an Andrew Wyeth painting, one of those ones with broken fence posts in the snow.

To read a book this way is more than a metaphor to me now. I realize now that I had thought of myself as a literate person, and all the while I had been reading in the same stolid way I had been taught in first grade, from beginning to end, and at a steady pace. I had never revisited the usefulness of that way of reading a book. Now I was reading differently. I liked it. What I’m trying to describe here is a deep attention. A willingness to be open to the unexpected. A willingness to forge your own path through a book, and to take your time, and to withhold judgment of both the book and yourself. To listen and forgive. To learn to read anew. Go see some art. Then, read a book.

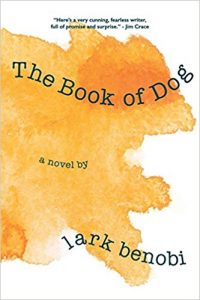

– Lark Benobi

(buy The Book of Dog by Lark Benobi

Lark Benobi is the playful pen name of freelance writer and novelist Claire Tristram. In addition to The Book of Dog she is the author of the novel After (FSG), and of short stories published in Fiction International, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Massachusetts Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, North American Review, and many anthologies.

She has written essays for Wired, Salon, Fast Company, the New York Times, and the Chicago Tribune, and is four-time Article of the Year winner from the American Society of Journalists and Authors. She began writing The Book of Dog on election night 2016, and drew inspiration for her story from the women who are speaking out, running for office, marching, and doing all they can to improve our world. Lark lives in Santa Cruz, California.

You can find out more about the book at larkbenobi.com.

About THE BOOK OF DOG

It’s the night of the Yellow Puff-Ball Mushroom Cloud and a mysterious yellow fog is making its way across America, sowing chaos in its path. Mt. Fuji has erupted. The Euphrates has run dry. The White House is under attack by giant bears, the President is missing, and the Vice President has turned into a Bichon Frise. It’s Apocalypse Time, my friends. Soon the Beast will rise. And six unlikely women will make the perilous journey to the Pit of Nethelem, where they will stop the Beast from fulfilling his evil purpose, or die trying.

It’s the night of the Yellow Puff-Ball Mushroom Cloud and a mysterious yellow fog is making its way across America, sowing chaos in its path. Mt. Fuji has erupted. The Euphrates has run dry. The White House is under attack by giant bears, the President is missing, and the Vice President has turned into a Bichon Frise. It’s Apocalypse Time, my friends. Soon the Beast will rise. And six unlikely women will make the perilous journey to the Pit of Nethelem, where they will stop the Beast from fulfilling his evil purpose, or die trying.

The Book of Dog is a novel of startling originality: a tale of politics, religion, demon possession, motherhood, love, betrayal, and easygoing bestiality. A ridiculously plausible story set in a near-future America, it wryly explores how even the most insignificant and powerless of people, when working together, can change the world.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers