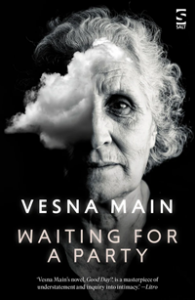

Authors Interviewing Characters: Vesna Main

What is it like to be married for thirty years but experience your first orgasm only after being widowed in your sixties?

What is it like to be married for thirty years but experience your first orgasm only after being widowed in your sixties?

How does an older woman change once she discovers her sexuality?

Could she have prevented the death of her husband? Why did she wait for an hour before calling the ambulance once she heard the thud of his body hitting the floor?

Claire Meadows, 92, a retired piano teacher, reflects on her life, while waiting to be taken to a 102nd birthday party of a friend, a prolific writer of detective stories. She has baked a cake for him, as she has done for the last seventy years.

She looks back on her marriage to Bill as a happy time and remembers without bitterness her husband’s secret visits to women whose calling cards, complete with pictures of them in states of undress, were scattered in the bottom drawer of his desk.

As a young woman she nurtured two ambitions: to become a concert pianist and to have children. When the former became incompatible with her role of a supportive wife, she accepted the situation and looked forward to becoming a mother.

But month after month brought disappointment; her kind husband was sympathetic, always ready to offer a shoulder to cry on.

Years later, she discovered the reason why she was unable to fall pregnant. And it was nothing to do with her.

Released from the bonds of her marriage, and encouraged by her feisty friend Patricia, a single mother, with few inhibitions, Claire embarks on a series of sexual encounters. She even fulfils one of the dreams of her youth in a way she could never have imagined.

As she lies in bed, waiting to be taken to the party, Claire relives the details of her affairs with relish. She continues to harbour sexual fantasies and wonders whether there is someone who could still find her desirable.

Vesna Main Interviews Claire Meadows

V: Claire Meadows, hello. Thank you for agreeing to speak to us.

C: Thank you to you for writing a novel with a female protagonist of a certain age. Most stories are about the young and beautiful. We older women are more often written off, than written about.

V: Indeed. My interest was piqued a few years ago when I saw a letter in a national newspaper from a woman in her early nineties. She wrote that her lover of twenty years, a man in his late eighties, had told her that he had found someone else. She was devastated and what shocked her most was not so much his behaviour, but her response to the situation. How come that at her age she needed a man, how come she missed physical intimacy so much? she wondered.

C: Of course she did. I still have sexual desire. The problem is not with us but with a society that cannot relate to us as sexual beings.

V: But, to their credit, other readers wrote to reassure the woman that anyone, regardless of age, has the right to affection and sexuality.

C: That’s good to hear. And I can tell you that there are many elderly people who are sexually active in their seventies, eighties and nineties.

V: Yes, I have had a number of women tell me their stories.

C: But you chose mine. I am pleased because I remember how shy I felt the first time I saw you and we eyed each other from a distance. I needed confidence, I needed time to summon the courage to tell you that I had my first orgasm when I was a widow at sixty, after thirty years of marriage.

V: I appreciate it takes guts to confide in a writer. Most of the tale came out in dribs and drabs.

C: But you were patient, waiting until I was ready.

V: I was grateful for your story. I am used to working like this: an initial impulse leads to questions and I wait. I don’t know where the narrative is going. I have no idea of the ending. The slow discovery of a story is both beautiful and intimidating. I compare the progress to a photographer submerging photographic paper into the developing chemicals and waiting for the image to emerge. Or not. And even when it does appear, it is often a surprise, sometimes a disappointment. With writing, I have to believe that the story will tell itself.

C: I don’t think what happened to me is typical but, as you know, I am an avid reader, and it seems to me that you chose my story over others because it made a strong point about older women. The novel tells the reader, not only are older women sexual beings but it is fine to be a late starter. Better late than never.

V: Exactly. Do you have any regrets about anything in your life?

C: When I was telling you my story, as you say, slowly and tentatively over a long period of time, I had the feeling that you were keen to know about my failure to become a concert pianist. You asked whether I thought I had any achievements to merit a public obituary. I sensed that you asked the question because you feared you were a failure and, given another chance, would have proceeded differently with your life. I replied facetiously. We both laughed and you said you agreed with the values underpinning my fictional obituary.

As for regrets, I don’t see the point since we cannot change the past, not even our dark secrets. But perhaps, if I had my life again, I would work towards realising my ambition to become a professional musician. However, I must stress that I had a good life, and it was only after Bill’s death that I realised that some of his behaviour towards me was not correct. Patricia kept nagging me to stop behaving as Bill’s little Claire, urging me to be my own woman but, at the time, I ignored her. I thought she was being unfair because she didn’t like Bill. But no regrets. Had I lived a different life, I wouldn’t have known Zach and Gabriel, the people I love most. They brought me more happiness than anyone else. What a miracle: my son Zach. And I wouldn’t have met the man at the concert. Joseph M. Labinsky was a true professor of sensuality. He died years ago but the memory of our time together still stirs a fire in me and I reach for my vibrator. Yes, at ninety-two. Rejoice, rejoice older women. As long as your health persisits, age is bliss, free from the anxieties and uncertainties of youth.

V: Thank you.

C: Can I ask you a question?

V: Of course.

C: The novel is structured as a memory with the protagonist’s thoughts moving from one event to another, in a seemingly random fashion. Those memories are punctuated by her thoughts about the day in prospect as she waits to be taken to the 103rd birthday party of a friend. Why did you decide to present the protagonist’s life in this way?

V: As always, it is trial and error. The first draft opened when she is 62, with the event which was a kind of epiphany and marked the rest of her life. I followed that path with a long flashback to the time when she was twenty and then moved on chronologically. I tried first person and third person and didn’t like either. Eventually, I arrived at the current structure and it seemed to me it worked much better since our thoughts, our memories from different periods of our life merge and diverge, rather than moving in a chronological sequence. And I settled for a third person narrator, suggesting a detachment from her earlier selves, but with a focaliser, that is, from the point of view of Claire. We see her life through her eyes and her, necessarily, limited vision. Instead of chapters about separate events, we have one continuous narrative, suggesting a train of thought.

BUY WAITING FOR A PARTY HERE

—

Vesna Main studied Comparative Literature, before obtaining a Phd in Elizabethan Studies from the Shakespeare Institute at the University of Birmingham, UK.

Her published fiction includes a short story collection, Temptation (Salt, 2018), a novel-in-dialogue, Good Day? (Salt, 2019), which was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths prize, an autofiction, Only A Lodger . . . And Hardly That (Seagull Books 2020), and a novella, ‘Bruno and Adèle’ in Shorts III (Platypus Press, 2021). Two of her stories are published in Best British Short Stories (Salt 2017, 2019); many others have appeared in journals in print and online. Waiting for A Party, Main’s latest novel, will be published by Salt in November 2024.

Category: Interviews, On Writing