Beth Kirschner: On Writing

There are certain places that have such a distinct personality, that they make an indelible impression that’s difficult to forget. Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula is one of those places. The diversity of the landscape, the challenges of the winter weather, and the uniqueness of those who call that place home all compelled me to write Copper Divide. This historical novel is set during the sunset of the Keweenaw Peninsula’s prominence as the world’s supplier of copper and as the state’s economic powerhouse. It chronicles one woman’s story of friendship tested by a society torn apart by a labor strike that resulted in the 1913 Italian Hall Disaster.

There are certain places that have such a distinct personality, that they make an indelible impression that’s difficult to forget. Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula is one of those places. The diversity of the landscape, the challenges of the winter weather, and the uniqueness of those who call that place home all compelled me to write Copper Divide. This historical novel is set during the sunset of the Keweenaw Peninsula’s prominence as the world’s supplier of copper and as the state’s economic powerhouse. It chronicles one woman’s story of friendship tested by a society torn apart by a labor strike that resulted in the 1913 Italian Hall Disaster.

While many author’s follow the dictum to “write what you know”, I am also fond of the corollary to “write what you want to know” (something attributed to Anthony Doerr’s process).

People still take sides on what happened that Christmas Eve over one hundred years ago, and even when memories were fresh, there were widely divergent stories regarding what had happened. While I spent several years living in the area, I recognize that I am an outsider. As an outsider, I felt I could be both a dispassionate observer and empathetic listener to all sides of this contentious moment in history.

Before I could write this story, though, I had to dive into the research. This took me down a path of discovery that was almost as satisfying as writing the book. I learned so much, from both primary and secondary historical sources. My research was more like a journey with many side-trips, some dead-ends and some not, some which made it into the novel and some which did not.

I found and visited two well respected historical libraries. Michigan Technological University has a vast historical collection (known as the “tech archives”) with diaries, newspapers, maps and many other interesting sources. The University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library is another treasure trove.

I started with the facts of the tragedy itself. This was the launching point of everything. I read newspaper accounts of what happened and collected books. I’m in debt to the detailed, scholarly works by Arthur Thurner (“Rebels on the Range”) and Larry Lankton (“Cradle to Grave”). But that was only the beginning.

I had a young Jewish protagonist in the story, which led me to wonder what were the dating customs at the time? What would be found in her home? What clothes would she wear? The jstor.org digital library was a huge source of information for these roving questions.

Another protagonist was a Finnish labor organizer. What was her daily life like? Her husband and children? How much did things cost when she went shopping? Did she have running water, and if not, where would she bathe? How did she travel around town?

The third protagonist was a scab miner, brought in from Chicago to cross the picket line. What would bring someone to this decision and why? What sort of jobs would he have held in the past and what was it like to physically work in a copper mine in 1913? I once had taken a copper mine tour, before the mine levels were allowed to flood, and dropped a pebble down one of the mine shafts. I never heard it hit bottom. Some of the mines were nearly one mile deep. How long did it take to get to the bottom of the mine and how did they get there?

The labor movement itself was a fascinating subject all by itself. I learned about the Industrial Workers of the World and their colorful nickname of “Wobblies”. The hopes and dreams of the socialists and anarchists and the labor organizers overlapped with each other and conflicted with each other. I read “The Jungle” by Upton Sinclair.

I also revisited the towns where the story takes place. I walked around Houghton, Hancock, Lake Linden, Calumet, Freda and other small towns scattered across the Keweenaw peninsula. I talked with anyone and everyone to collect trivia and anecdotes. I toured the copper domed synagogue that opened in 1912. Every discovery prompted another question. I found a wonderful locally published book by David Mac Frimodig (“Keweenaw Character”), which served as the catalyst for several of the minor characters in the novel.

There were some fun facts that I knew had to make it into the novel, including how to maintain passable roads with over three hundred inches of snow and no snow plows, how to roast your own coffee beans, and how to live off the land if one chose to be a hermit in 1913.

There were also serendipitous discoveries, such as the ship wreck memorial I found at a Michigan lighthouse hundreds of miles away from Calumet, which listed a wreck that occurred at the very same time and place as my story!

Over the course of my research, I had to decide whether to put actual historical figures into the story, or to merge them into composite characters. I mostly chose the latter, since it provided more opportunities to blend actual events with compelling characters.

Writing a historical novel was a great excuse to follow a self-directed path through history and learn a great deal along the way. It was my hope that the background information made the characters more three-dimensional, and made the time and place more memorable. I have no regrets on the time spent combing through the historical record, as it allowed me to almost feel as if I had been there myself.

—

Beth Kirschner grew up in upstate New York, and thought she knew everything there was to know about winter snows until she moved to Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula for college. There she discovered an average snowfall between 200 and 300 inches, and a record winter snowfall of 390 inches. In addition to the harsh winters, she found a place rich with history, personality, and the world’s only known source of pure, native copper. The Keweenaw Peninsula is the setting for her debut novel, Copper Divide.

Her writing has moved from poetry to travel journals, short stories, and novels. When not writing, she works as a software engineer, flies single engine airplanes, and enjoys exploring Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. She has two grown children, two large cats, and a room of her own for imagining her next story.

Read more on https://medium.com/@beth_kirschner

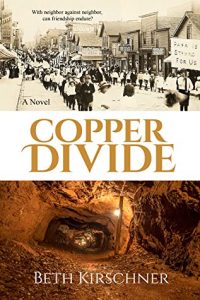

COPPER DIVIDE

In 1913 a massive and violent copper miners’ strike has split the once peaceful community surrounding Calumet, Michigan. Thousands are protesting and rioting in the streets. The National Guard is sent in and stays for months.

In 1913 a massive and violent copper miners’ strike has split the once peaceful community surrounding Calumet, Michigan. Thousands are protesting and rioting in the streets. The National Guard is sent in and stays for months.

Hannah Weinstein is a Jewish merchant’s daughter, certain that the interruption of her college classes is the worst the strike will bring to her relatively comfortable life. Her Finnish friend Nelma, however, is married to a striker, and places herself on the front lines of the dispute.

When a train pulls in with a hundred scab miners, tensions escalate, and two of the scabs are shot. Their murder compels Hannah to join a Citizens’ Alliance opposing the strike – and with it, Nelma. As the strike grows more and more deadly, Hannah and Nelma must find a way to reconcile and end the conflict without further violence, or their town – and their friendship – will be destroyed forever.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

This is a fascinating historical event to explore. Calumet was once considered for state capitol of Michigan due to the copper boom. My grandparents were copper miners–and the family story is that my maternal grandmother was at the Christmas party at the Italian hall.

I self published a book that looked back on the Finnish community in the Keweenaw peninsula. (Aliisa’s Letter)