Diva Mamas—Reluctant Mothers in Literature

Happy Mother’s Day to all women for we are mothers both to ourselves as well as to others!

Happy Mother’s Day to all women for we are mothers both to ourselves as well as to others!

And as Mother’s Day approaches, we are surrounded by cards and suggested gifts in the image of the perfect mom. The fictional mothers I will focus on are reluctant mothers at best, who hesitantly take on the responsibilities of motherhood, let alone the joy. Depending on the woman, the mother can and has taken on many forms throughout literature. Some of the most memorable are “mothers from hell”. These mothers are spectacularly awful.

I tried to think of some of absolutely the most narcissistic mothers who were so often cruel, spiteful, needing attention, and betraying the ones who trust them and want their love. I omitted those harboring murderous intentions, although they often make wonderful page-turners.

But the best of the best portrayals of the reluctant or even the despicable mother still have glimpses of insight into their own nature as well as their children and often have broken dreams themselves. Being a mother is just one of many dissatisfactions in life.

Motherhood for many of these fictional mothers is simply an afterthought. Yet these women suffer—from being trapped inside their own skins with fates they had not chosen. Their wounds make them cruel—often to themselves as well as their children, often clueless about their children’s needs because bad mothers are incapable of love.

This reluctant or narcissistic/injured mother presses the buttons of the reader—because she is the least likeable and least acceptable character in literature. In the end, it is a given that the bad mother never gets away with her heinous behavior and is always punished. That behavior can be the overbearing mother (Sophie Portnoy), the vain mother (Emma Bovary), or the wounded mother. I’ll focus on the last. It’s not easy to write off the wounded or narcissistic mother as the opposite of the sainted, glorified image of motherhood. She is real—both good (even if just a hint of that as a child) and bad, and all try to do their best, even if their best is just too off track to qualify for being a responsible, loving, but flawed mother.

Here are my examples:

Maine (J. Courtney Sullivan)—Alice Kelleher is an 83-year old dying mother, one who wanted forgiveness for a death she feels responsible for but no one was there to forgive her. So now she can’t forgive others, even though she asks God to help her be good. She had suffered three miscarriages before having children: “Alice wondered if in her case the children simply vanished because they knew they weren’t quite wanted or more to the point, that she was no mother.” And so “Maine” reveals a compelling backstory for the current dysfunction in the Kelleher family.

“August: Osage County” (a play by Tracy Letts)—Violet Weston, the scabrous 65- year old matriarch in this saga of secrets and lies astonishes the reader with her unforgettable hold on her daughters, husband and her son-in-laws.

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant (Anne Tyler)—[Ezra’s thoughts about his mother, Pearl Tull:] “ The fact was that she was a very strong woman (even a frightening one, in his childhood, and she may have shrunk and aged but her true interior self was still enormous, larger than life, powerful. Overwhelming.”

Olive Kitteridge (Elizabeth Strout): [Olive Kitteridge’ thoughts about her son, Christopher:] “She can almost not remember the first decade of Christopher’s life, although some things she does remember and doesn’t want to….It was how scared he was of her that made her go all wacky. But she loved him!”

Mrs. Bridge (Evan S. Connell): “Mrs. Bridge, having suddenly discovered Ruth was naked, snatched up the bathing suit and hurried after her. Ruth began to run,…She thought it was a game. Then she noticed the expression on her mother’s face. Ruth became bewildered and then alarmed, and when she was finally caught she was screaming hysterically.”

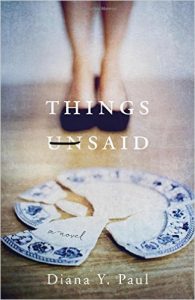

And from my novel, “Things Unsaid”: [Mother and daughter conversation]“’Mother, I want to help, to be a good daughter. But I don’t want to be like you. I just want to do the right thing.’ ‘Ha, why don’t you want to be like me I want to know! I’m your mother, and your father and I have done more than enough for you. Without us, there would be no Jules….We’re great parents.”

There is no how-to manual for motherhood, and if there were, the range of personalities would definitely not be a one-size-fits-all advice book. While we can enjoy the nostrils flaring and ghastly fangs bared in diva-mamas in literary fiction, it is gratifying to suspend our own experience and squirm while we are deliciously drawn into these family sagas, which propel us into the power of mother as primal, and the first human connection we all have.

—

Diana Y. Paul, born in Akron, Ohio, is a graduate of Northwestern University, with a degree in both psychology and philosophy, and of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, with a PhD in Buddhist Studies. Her debut novel, Things Unsaid (She Writes Press, 2015), has been ranked #2 in the “Top 14 Books about Families Crazier Than Yours” and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Diana Y. Paul, born in Akron, Ohio, is a graduate of Northwestern University, with a degree in both psychology and philosophy, and of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, with a PhD in Buddhist Studies. Her debut novel, Things Unsaid (She Writes Press, 2015), has been ranked #2 in the “Top 14 Books about Families Crazier Than Yours” and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

A former Stanford University professor, she is also the author of three books on Buddhism, one of which has been translated into Japanese and German (Women in Buddhism, University of California Press). Her short stories have appeared in a number of literary journals and she is currently working on a second novel, A Perfect Match. She lives in Carmel, CA with her husband, Doug, and their white-and-grey calico, Mao. Diana and Doug enjoy visiting their two adult children, Maya Miller ( San Francisco) and Keith Paul (Los Angeles), as often as they can.

To learn more about her and her work, visit her author website at http://www.dianaypaul.com and her blog on movies, art, and food at http://www.unhealedwound.com or follow her on Twitter: @DianaPaul10. Visit her author website, http://www.dianaypaul.com for more information.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Astrid’s mother, Ingrid, from White Oleander by Janet Fitch