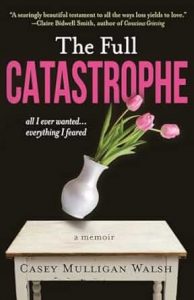

EXCERPT FROM The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared by Casey Mulligan Walsh

THE FULL CATASTROPHE: ALL I EVER WANTED, EVERYTHING I FEARED, Casey Mulligan Walsh

Casey needs a family of her own: the joys and the sorrows, people who love her, and a place she belongs-what Zorba the Greek called “the full catastrophe”-and she’s determined to make it happen.

Casey needs a family of her own: the joys and the sorrows, people who love her, and a place she belongs-what Zorba the Greek called “the full catastrophe”-and she’s determined to make it happen.

Adrift in the world after losing her father to a heart attack when she was eleven and her mother to cancer soon after, the death of her only sibling eight years later strengthens her resolve.

Casey marries, has three children, and though she struggles with grief and a shaky sense of her place in the world, she thinks she’s found the life she’s longed for. But soon it’s clear her marriage isn’t the dream she envisioned. When her husband’s behavior shifts from troubling to destructive, a contentious divorce and custody trial propel her family into a catastrophe she never imagined. Searching for meaning, Casey embraces the spirituality she’s sought in various forms since her youngest years. Then the unthinkable happens-her twenty-year-old son Eric dies-and she’s left to make sense of her family’s collapse and the sudden yet somehow inevitable loss of her beloved boy.

A profoundly moving tribute to the power of love, The Full Catastrophe is the story of a life of loss and sorrow transformed into one of hope and redemption. With hard-won wisdom, Casey shows us how peace and belonging can only be found within ourselves.

EXCERPT FROM The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared

On June 12, 1999, a beautiful Saturday afternoon, my oldest son was killed in a car crash. The multiple losses I’d experienced as a child and young adult had set me off on a search for home and belonging that would guide the choices I made for decades to come. But by the time this tragic day arrived, I’d embraced a spirituality larger than my circumstances and had begun to understand the things I needed most were already within me.

This excerpt begins weeks after my son’s death.

I’m listening to Sondheim and wading through a sea of bills when the phone rings.

“Eric Simonson, please.”

“Sorry, he’s not here.”

You have no idea how sorry I am he’s not here. But god, it feels so good to hear someone say his name again.

“We’re calling about a $60 check he wrote to Price Chopper on October 7th, 1998. It was returned for insufficient funds.”

“Seriously? That was nine months ago.”

“With fees, he now owes $82. If he doesn’t pay right away it goes to our lawyer.”

I drop into my worn-out computer chair and stare out the bank of windows into the back yard. The old barn leans to the left, tilting in the direction of the abandoned basketball hoop.

“Hello? How can we get in touch with him?”

Glancing at the sympathy cards and still-unopened boxes of thank-you notes stacked on the side table, I mumble, “He’s dead.”

“Dead?” I detect a note of skepticism.

“Dead. He died on June 12th.”

Eric’s death, so quickly old news for the rest of the world, though it’s only been six weeks. But the telling makes it real again. Makes him real. They say his name and it brings him back, if only for a moment.

I have to remind myself Eric isn’t away at college or basic training, that he won’t burst through the door at any moment, calling, “What’s for dinner, Mom?” as he grabs his swimsuit and heads right back out to the lake. Some days—like today—I begin to picture this, then force myself to think about something else. It’s too hard, too fresh. Not yet.

It felt as if my own life began when Eric was born. If marriage made me a wife and having Eric made me a mother, then bringing him home made the three of us a family, the very dream I’d been chasing since I lost my own family at twelve. Soon we had another son, then a daughter, and—despite difficulties in our marriage—I thought I’d created the life I’d longed for and the belonging that had eluded me for so long. But it didn’t last.

“We’re sorry for your loss.” The voice in the phone jars me back to the present. “Just send us a copy of the death certificate.”

“No.” It falls out of my mouth before I even have time to think.

“No? Ma’am, we’ll need a copy of the death certificate.”

My words come out in a rush. “Sorry, I’m not sending you one. It’s public record. What’re you gonna do, have him arrested?”

Standing in the great room now, the cordless phone to my ear, a sigh escapes me. My attention drifts, and I use my free hand to wrestle the wooden filing cabinet drawers closed. They’re falling apart, overflowing with the bills, family court documents, and school records lawyers insisted I produce during our protracted divorce and custody battle. There is, at last, nothing left to prove.

I’ve been proving myself forever.

Staying with friends when my parents were ill, living with relatives after they both died, then folding myself into my husband’s family as though I’d always been there, I became adept at finding ways to fit in. If I alternated between smiling sweetly and proving my worth, I hoped I could strike just the right balance. Maybe I could fool them all into accepting me as the permanent, no-matter-what-happens family member and friend I longed to be.

“We’re attempting to collect a debt. Someone has to take care of this, or you’ll have to send us the death certificate.”

“I understand. I just won’t do it.”

This refusing to explain, producing no evidence is strangely exhilarating. Freeing. Sympathetic to the caller—she is, after all, only doing her job – I stop short of being rude, sticking instead to statements of fact. Several volleys later, collection lady wholly unsatisfied, I hang up.

Week after week well into the fall, I answer the phone to hear a new caller with the same familiar request: “We’re looking for Eric Simonson.”

I’m sure the fact that Eric has died is right there on the screen, so I’ve run out of patience for gentle disclosures of his passing.

“You’re going to have a hard time reaching him.”

“Would you like us to stop calling?” She skips feigning ignorance and jumps directly to impatience.

I draw in a deep breath, then let it out slowly. “You bet.”

“Then send us a death certificate.”

“Sorry, nope. Talk to you soon.”

I can’t pin down the complicated feelings these calls evoke. As annoying as they are, these requests remind me Eric’s still my son. I’m still his mother.

Yet finally I’ve had enough.

I arrive home from work one evening in early fall, toss a piece of salmon on the grill, and run for the phone jangling inside. Balancing the tongs on the empty plate in one hand, I grab it on the seventh ring.

“Eric Simonson, please.”

I ran into the house and nearly dropped my dinner for this?

“Listen, he’s dead. He was dead the last time you called, he’s still dead, and he’s probably gonna be dead the next time you call. Why don’t you just save your breath and stop calling?”

Months later, I realize they did. I couldn’t have known we’d had our final skirmish until the phone went deafeningly silent.

I’m sad the battle’s over; now there’s no one calling for him, saying his name.

But Eric’s is not the only name I long to hear.

I’d have given anything to hear “Aren’t you Bob and Elizabeth’s girl?” just once through my teens and into adulthood, when I yearned to know people who had known them. Their absence left a hole I spent decades trying to fill; no matter how fast I shoveled or how rich the soil, the pit remained.

Though I couldn’t rewrite my own history, I’d been certain I could protect my kids from this same ache by putting down deep roots in a small village. Yet even this didn’t save them from the pain and struggle I’d have given anything to prevent.

Maybe it’s genetic, that elusive sense of being entitled to a place in the world. Maybe some—the lucky ones—inherit the secret code and pass it down to their children.

I wondered how that would be, for far too many years, waking up in the world like you already knew you belonged there.

—

Casey Mulligan Walsh writes about life at the intersection of grief and joy, embracing uncertainty, and the nature of true belonging. She has written for The New York Times, HuffPost, Next Avenue, WebMD, Split Lip, Hippocampus, and numerous other media outlets and literary journals. Her essay, Still, was nominated for Best of the Net. She is a founding editor of In a Flash literary magazine.

Her work was included in Daring to Breathe, an anthology about living with the foreverness of grief. Casey is passionate about supporting those who grieve all manner of losses, including those that are spoken of and those too often shrouded in silence. Casey also serves as an ambassador for and on the Board of the Family Heart Foundation.

Casey lives in upstate New York with her husband Kevin, their chatty orange tabby, and too many books to count. When not traveling, they enjoy visits from their four children and ten grandchildren—the very definition of “the full catastrophe.”

Category: On Writing