Filling in the Gaps

Filling in the Gaps by Barbara Hoffbeck Scoblic

Filling in the Gaps by Barbara Hoffbeck Scoblic

As I worked on my memoir, Lost Without the River, I often realized that I needed details about events that occurred before my memory had kicked in. I was grateful my five remaining siblings were willing and able to fill in my blank spots. Remarkable. I’m the youngest, and almost eighty.

As a young woman I’d moved from a small farm in South Dakota to New York City, unaware of what I was losing. All of us siblings had moved to other states, but I’d moved the farthest. When I became a mother, the enormity of what I was missing became overwhelmingly apparent. No mother, or sister, or aunt to comfort my colicky son when he cried every day from 4:00 in the afternoon to 1:00 am. No relative to comfort me when I was overwhelmed with worry over my little one. As my two sons grew, there were no grandparents, aunts, or uncles to bring their loving presence to their baptisms, First Communions, graduations.

The distance seemed to expand when my parents’ health declined. Though I managed to see my parents and siblings almost every year, the visits were short. I missed many, too many, reunions, weddings, and funerals.

As I continued to write it became apparent there were gaps in my knowledge of our life on the farm. It was important to get everything right. I needed answers. Phone calls became an important link to my siblings. It would certainly have been more efficient to make these calls at my desk, which would have given me a flat surface on which to take notes, and easy access to what I’d already written. But I wanted to be comfortable and relaxed, so I’d brew myself a fresh pot of coffee, gather a pen and a notepad, pick up my cell phone, and move to my favorite place on the sofa. That spot became, in effect, my kitchen table.

Some phone calls might last only a few minutes; others went on for hours. At times I’d set a timer, and begin by saying, “I’m sorry, but I only have fifteen minutes today.” My siblings never seemed to be offended. After many years of my quizzing them, they were eager (and probably impatient) for me to finish the book. Other times I’d let the conversation meander, let the recipient determine the time limit. As we remembered our days together and the struggle our parents had endured on the farm, we often laughed. A few times we cried.

At last my manuscript was finished. One day as I was proofreading the galleys I realized I might have given name to the wrong insect. I picked up my cell, and inadvertently interrupted my brother Bob’s breakfast.

I was on deadline. No time for pleasantries. “Were those bees or wasps that built a home beneath the eaves of our house?”

His answer was short. “Bees.”

So my wording had been correct. But when I mentioned that conversation to Bill, another brother, he added a new dimension to the story, one, unfortunately I couldn’t add because of time constraints.

“Don’t you remember?” he asked me. “The bee hive was so productive, honey seeped down through the wall and stained the wallpaper in our parents’ bedroom. The room had to be repapered.”

Other times these conversations would segue to a completely unplanned subject. A question to Bob inquiring about a discouraging 4-H project of mine led him to relating a traumatic story that I’d completely forgotten. My mind had kept it hidden.

Only as Bob went into detail did I manage to recover a snippet of that awful day when I’d almost accidentally killed him while we’d worked together to complete a farming chore. As he talked, an image of my younger self appeared. In it I was sitting on the couch in the living room of our farmhouse, alone, waiting to hear the doctor’s answer to the question: “Would my brother survive?”

All these years later I felt devastated. Tears came to my eyes. “I’m so sorry!”

My brother chuckled softly. “An apology isn’t necessary. It wasn’t your fault.”

For more than two years I phoned my siblings often. What I learned from those frequent conversations inspired me to add details and stories that enriched my memoir. Even more important, my siblings became enthusiastic companions through the lonely process of writing and editing. The voices and the laughter I heard during those calls pulled me back into the warmth of my family.

—

BARBARA HOFFBECK SCOBLIC began her writing career as a reporter for The Argus Leader in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. She now lives and writes in New York City. Visit her at www.barbarascoblic.com.

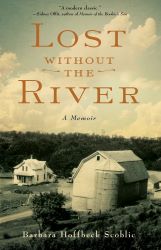

LOST WITHOUT THE RIVER

Barbara Hoffbeck never quite felt she fit into the small farming community of Big Stone City, South Dakota—and as the youngest of seven growing up during the post-Depression era, she struggled to find her place within her large Catholic family. Barbara defied expectations at every turn, determined to prove her worth in a male-dominated time and place, whether it be by joining a “no girls allowed” hunting trip with her brothers, racing to help save her family’s burning barn, or moving across the United States to New York City to pursue a career in publishing.

Barbara Hoffbeck never quite felt she fit into the small farming community of Big Stone City, South Dakota—and as the youngest of seven growing up during the post-Depression era, she struggled to find her place within her large Catholic family. Barbara defied expectations at every turn, determined to prove her worth in a male-dominated time and place, whether it be by joining a “no girls allowed” hunting trip with her brothers, racing to help save her family’s burning barn, or moving across the United States to New York City to pursue a career in publishing.

Barbara took her experiences in stride, grounding herself in the beauty of her surroundings—an appreciation stemming from her Dakota roots. Lost Without the River is the story of a girl who grows up, leaves home, and eventually discovers an appreciation for the farm she left behind. It demonstrates the emotional power that even the smallest place can exert, and the gravitational pull that calls a person back home.

Category: On Writing, Women Writers

Barbara, your delicious article about your memoir brings to mind a topic with which I have dealt …. no matter what happens and how I feel about it or think about it, in order to be true to myself and to my gifts, I need to de-personalize a bit. Just as being pulled into the dramas of our friends or clients requires boundaries, so do the fine details of a vignette in a memoir. I think it’s moving through experience to creating something new. Best wishes,

Mary Latela

@LatelaMary

maryellenlatela@gmail.com