From Medicine to Writing to Crime: a Natural Progression? By Anne Pettigrew

By Anne Pettigrew

You don’t have to search far to find medically trained folk who’ve become writers. For example, Anton Chekhov, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Richard Gordon, Michael Crichton, Khaled Hosseini, Adam Kay and Freida McFadden were qualified doctors. Even Agatha Christie, the world’s most successful crime writer (two billion book sales) was ‘medical’, being a pharmacy dispenser. I’m in good company as a retired Scottish GP writing novels about medical women battling danger, dodgy doctors and disappearing patients in the patriarchal medical world. So, why I wonder, do so many medics write successfully?

Admittedly, literature has geniuses without personal experience who can write about pretty well anything using research and professional advisors. Yet for writing medical or crime novels, us medics must have advantages. We can authentically portray medical settings and jargon. We have knowledge of poisons and potentially undetectable means of ‘body despatch’ for plots.

Perhaps most importantly, we’ve had the advantage of unique doctor-patient consultations. Since Hippocratic times, patients anxious to stave off the Grim Reaper offer uber-frank information about emotions and feelings. Our training allows us to plumb the depths of the human psyche that consultations expose, and what they reveal about thousands of situations and relationships aids us in developing characters and plots. Arguably, the motivations of bean-spilling clients in confidential legal interviews differ. Lawyers seek more fact-based testimony. Still, they must also learn much about the human condition and there are many lawyers who write such as Kafka, Grisham and Kirstin Hannah.

Over thirty years as a family doctor I’ve been privileged to hear thousands of patients’ stories: surprising, enlightening, funny, sad, horrifying. More than once, I’ve thought them unbelievable. Fact can indeed be stranger than fiction. Lord Byron agreed. His poem Don Juan (1824) suggests putting more fact into novels would better ‘show mankind their souls’ antipodes.’ Just how dark these hidden souls can be I’ve discovered. Writing villains is definitely more fun!

Beyond the consultation room, we docs revolve through hospital clinics, meetings, teaching, interacting with colleagues in multiple disciplines and encountering rudeness, devious colleagues, prejudice, blunders and unexpected consequences. Excellent for plots!

Other workplaces doubtless have similar, but medicine has an edge: day on day dramas of life, death and grief with all human life and personality types exposing emotion, pain and panic. A perfect training ground for the novelist. Personally, I have a moral disquiet (and a fear of lawsuits) about memoirs revealing patient specifics. Though Oliver Sacks and others have successfully produced detailed non-fiction case histories, I have long been drawn to writing fiction.

But while voices and experience fed into my writing, it was a 2003 sabbatical year at Oxford University which made me objective enough to write candidly about medicine. Studying for a Medical Anthropology Masters assessing medical beliefs and practices across the world and in history to inform new avenues for health promotion, I discovered the ‘Medicine’ I knew was only a construct.

Patients ‘culturally’ present symptoms to ‘fit’ diseases doctors have invented. Diseases are named only to aid discussions of treatment and can change depending on cultures and era like the patient fearing evil spirits in the UK who’s diagnosed Schizophrenic. In Kenya? Normal. Or those fainting Victorian girls with ‘Chlorosis’, a redundant diagnosis lost in time. I graduated with my tutor satisfied I’d been ‘deconstructed!’

In retirement I drafted a medical novel exposing women’s inequality in hospital medicine. Finding it hard, I took university creative writing courses and discovered such niceties as characterisation, pace, dialogue, the essential art of ‘showing’ not ‘telling,’ and how to brutally edit by ‘murdering my darlings’ (a phrase attributed to Arthur Quiller Couch, 1814). My novel’s theme switched to medical students in the sixties after encouragement from fellow course undergrads. How did we socialise then without cell phones? Research without Google? Have sex without the pill?

So, book one became Not The Life Imagined, a pacey tale of surviving life as a med student and junior doctor in sixties and seventies Glasgow. Its villain, Conor, epitomises everything you wouldn’t want a surgeon to be.

Book two, Not The Deaths Imagined, has same character Beth, as a GP putting her family in peril as she attempts to whistle blow about a possible serial killer colleague. Murder just crept in to my writing. Unsurprising, since us docs know how death happens. Serendipitous, as research shows readers adore a good murder.

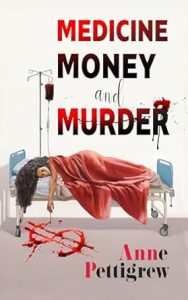

My third medical thriller (September 2024, Sparsile Publishing) is Medicine, Money and Murder where 1971 female Glasgow med students in a US hospital summer placement find blackmail, disappearing patients and murder. We privatize the NHS at our peril…

Why other docs write I know not, but my motive is primarily to record the multiple barriers women medics faced long before #MeToo. Women doctors are largely absent from literature except as tokens or historical figures. I also want to show how the General Medical Council tenets of care, compassion, competence, trust, and sexual propriety can be subverted. Sometimes easily. Not all medics are altruistic.

Mostly though, I want to entertain, serve a rollercoaster story involving humour, student antics from naive times past, some romance and a murder or three. Like Michael Crichton, I am happy being considered a holiday ‘read’ though pleased my themes have stimulated book clubs.

Yes. Medicine, Writing and Murder transition easily into one another. As do Medicine, Money, and Murder….

Dr Anne Pettigrew

Scottish author Anne is a Bloody Scotland Spotlight author. A former GP and journalist, she is a graduate of Glasgow (Medicine, 1974) and Oxford (Anthropology, 2004). Since retiring, she’s written three feminine lead sixties/seventiesmedical mystery novels and one teacher led murder mystery set in Oxford during the Iraq War. Her debut novel, Not The Life Imagined was runner-up in the Scottish Association of Writers’ Constable Silver Stag Award. Her second, Not The Deaths Imagined, is a murderous sequel highlighting the perils of whistleblowing. New editions have been republished by Sparsile Books. Her third medical crime novel, Medicine, Money and Murder, set in 1971 USA, is out in September 2024. The Oxford book, The Carnelian Tree, is published by Ringwood Publishing. She lives in North Ayrshire, loves travelling, food, and wine – and reader reviews which will help sell more books to benefit children’s charity PlanUK!

Sign up to her website: http://www.annepettigrew.co.uk

Facebook @annepettigrewauthor I

Twitter @pettigrew_anne

MEDICINE, MONEY AND MURDER

MEDICAL MURDER IN AMERICA

It’s summer 1971 in New Jersey. Scottish medical students Mhairi and Laura are on work placements in the USA. But very soon they realise all is not well in the outwardly peaceful and prosperous Ellis Memorial Hospital.

It’s summer 1971 in New Jersey. Scottish medical students Mhairi and Laura are on work placements in the USA. But very soon they realise all is not well in the outwardly peaceful and prosperous Ellis Memorial Hospital.

Though finding commercialised US healthcare alien to their NHS experience, they are more troubled by sinister incidents, strained staff relationships and the mysterious disappearance of a charity patient.

Just who are Dr Juan Mendoza’s Sunday Morning patients with their special nurses?

Why does the abrasive and aloof Dr Elias van Lindholm hold such sway?

And exactly what ‘research’ is Elias doing with their fellow student, Frankie Cooke?

When a patient vanishes, another is nearly murdered, and one of the students is killed, Mhairi and her US boyfriend John must unravel a web of lies, blackmail and murder, before the killer strikes again.

Medicine, Money and Murder leads the reader through a thrilling thought-provoking tale of crime, ethical dilemmas, romance and cultural clashes, before ending in a final explosive climax.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips