From Screenwriter to Novelist

I first wanted to become a novelist because I wanted to find out how it was done. I remember as a teenager being gobsmacked when I read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s last novel, Tender Is The Night, in an edition that explained how two different versions had been published, the second re-arranging the chronology of the story according to his posthumous notes. It opened my eyes to how even a ‘great’ and ‘classic’ author like Fitzgerald had been engaged in a process and gone on struggling with his book even after it had been published.

I first wanted to become a novelist because I wanted to find out how it was done. I remember as a teenager being gobsmacked when I read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s last novel, Tender Is The Night, in an edition that explained how two different versions had been published, the second re-arranging the chronology of the story according to his posthumous notes. It opened my eyes to how even a ‘great’ and ‘classic’ author like Fitzgerald had been engaged in a process and gone on struggling with his book even after it had been published.

That glimpse of a work in progress caught my imagination and never left. An English degree didn’t shed enough light on the nuts and bolts of how and where to start writing a novel, and I went into journalism where the ‘rules’ seemed fairly straightforward – or where, at least, I could learn quickly from my mistakes! I also began to write about decorative arts, fascinated not only by how potters, weavers, textile and wallpaper designers and furniture makers made things, but also how their work reflected their time and place.

I’ve always thought that crafting a screenplay or novel is like making a chest of drawers: it not only has to look good and be fit for purpose, but also function flawlessly; a good story, too, should slide along as smoothly as pulling out a drawer with one finger.

I wrote my first screenplay for the BBC nearly thirty years ago. It was a revelation. It helped that I’d come from journalism where I’d mastered deadlines, writing to length, tailoring each piece to a specific newspaper or magazine and also pitching ideas in the first place. I discovered that screenwriting was all that and more – and I loved it!

Since then I’ve contributed dozens of episodes to popular TV drama series, including The Bill, Wycliffe, Midsomer Murders and, with Jimmy McGovern, the BAFTA and International Emmy-winning Accused, and well as docu-drama, film and radio drama.

Writing a screenplay is like building a house rather than a chest of drawers: it has to meet the spec and be finished on time, everything has to fit, everything has to work and the client has to want to live in it. There’s a lot of brainstorming, meetings, chucking ideas out and re-drafting, notes and more notes, and, occasionally, rejection.

A screenplay has to be tightly structured because the story is going to be physically made. It’s going to be carved up by a small village of people into locations and casting calls and budgets, yet still has to work once it’s all put back together again. So the producers need to be as sure as they can be that their vast amounts of money and effort won’t be wasted.

But it’s huge fun, and there’s nothing more wonderful than watching a director and actors – and all the other essential crew – take my script and turn it into something so much more.

When I began writing novels, I was glad of the skills I’d acquired as a screenwriter – I now knew how strip down an engine and put it back together. Yet it’s taken at least four novels to realise that, even in crime fiction, too expertly structured a story is a drawback, that, over the much greater length of a novel, careful planning can become predictable and dull to write, and that the narrative works so much better when given room to breathe.

When I began writing novels, I was glad of the skills I’d acquired as a screenwriter – I now knew how strip down an engine and put it back together. Yet it’s taken at least four novels to realise that, even in crime fiction, too expertly structured a story is a drawback, that, over the much greater length of a novel, careful planning can become predictable and dull to write, and that the narrative works so much better when given room to breathe.

As a reader of novels I know I want to sit back and enjoy taking risks, ready to let a narrative to find its own pace and its own route to its destination – including slight detours; but I do dislike feeling lost, or experiencing a sense that my journey is irrelevant to the author. So what I hope I have brought from screenwriting to my fiction is a focus on my reader that urges me to create spaces in which she can ask questions, guess, wonder, be surprised, moved or shocked.

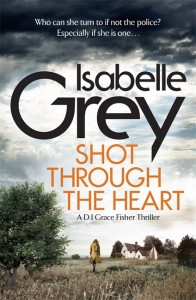

But I no longer plan my journey. Writing my latest novel, Shot Through The Heart, I found the courage to let go and, as I wrote, not always know where I – or my characters – were going. At first it was really scary to get halfway into the story – maybe two or three months of work – and wonder if it was ever going to turn out OK. But, with no reason to impose the micro-managing necessary to shooting (and financing) a film or TV drama, I have now learnt to enjoy writing under conditions of controlled panic.

Not even my editor wants to be told ahead of time how my story will end. I’m on my own – apart of course from all those unpredictable ‘people’ in my head! Yet what initially felt like a frightening void has turned slowly into a pleasurable and essential creative space. Without the punishing schedule of turning out successive scene-by-scene treatments and draft scripts, I can feel my way forwards more tentatively and explore directions that I might otherwise have rejected too soon.

I still love screenwriting, always will. But the experience of thinking like a novelist – of being inside the process I was so curious about when I was a kid – that’s pretty rewarding.

—

Isabelle Grey has written four novels published by Quercus. GOOD GIRLS DON’T DIE and the recently published SHOT THROUGH THE HEART are the first two books in a crime series set in Essex and featuring DI Grace Fisher. Isabelle grew up in Manchester and now lives in north London, near enough to Hampstead Heath to walk there regularly. Her writing is fuelled by chocolate and green tea.

Follow her on Twitter @IsabelleGrey

And on her blog www.isabellegrey.wordpress.com

Category: On Writing