How Stories Begin: I Was a Coward and Became a Writer

Stories, including those that develop into novels, begin in all kinds of ways. A real-life person you wonder about, a situation you read about in the paper, an intriguing name you feel would make a great character, something that keeps gnawing at your imagination—there are as many ways as there are plots.

Stories, including those that develop into novels, begin in all kinds of ways. A real-life person you wonder about, a situation you read about in the paper, an intriguing name you feel would make a great character, something that keeps gnawing at your imagination—there are as many ways as there are plots.

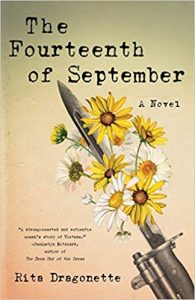

In my case, with my first novel, The Fourteenth of September, I’d always thought I knew where the story came from. I’d been on campus during the most turbulent years of the Vietnam War—1969-1970—the critical time frame of the First Draft Lottery and Kent State.

I knew it was an important piece of history. I’d mentally recorded dozens of “moments”—incidents, characters, and situations that were amazing illustrations of both the tragedy and absurdity of the times. A close friend had written me a letter after college telling me there was a story in those years and I was the one to tell it. I believed him and turned to this material once I decided I’d move into a second career as a writer.

My rationale seemed clear until I tried to put it on paper and it came out like recycled history: episodes strung together as if a theme or plot would emerge just from their painful retelling.

To help, I enrolled in a workshop at a major university to give me structure and decided that I’d use every writing exercise as something for my eventual novel. The first assignment was to write a prayer, which was odd but intriguing. Though I wasn’t at all religious, I remembered so many times in those days intensely “talking” in my head to some bizarre power to please make sure my boyfriend got a high Lottery number, that my linguistically gifted cousin would be assigned to a safe translator role in Europe versus action in Vietnam, that a close friend who’d chosen meth and starvation would fail his physical before he lost his mind.

I recalled an incident—the drama of which was fully formed—ready for the insertion of fictional prayer.

One night, I was in a classroom that had been taken over for a meeting to plan “action” to respond to the university administration’s efforts to close the campus after Kent State. It was the usual cast of characters representing various antiwar factions from the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War to the Students for a Democratic Society and the Young Socialists. But also, for the first time, there was an actual Vietnam vet in the room.

One of the moderators, trying to earn his radical chops, went after the vet, forcing him to admit that while “in-country,” he’d killed people. “We don’t listen to people who kill people,” the moderator said, whipping the crowd up to agree and taunt the vet. It was a shameless display of teenagers totally missing the point of the antiwar movement and taking it out on the very type of person they should be supporting.

I remember being dumbfounded, waiting—assuming—that any minute someone reasonable would stand and shut them up. No one did, and the vet rose, looked at us like we were the most ridiculous people in the world, and walked out of the meeting. I can still see it like it was yesterday.

For the writing assignment, it was easy to put Judy, my female character, into my place in the scene, “praying” in her head that someone would stand to stop the harassment. However, the scene only worked if there was more rationale—why was Judy so personally upset and intent as she yelled in her head, “Someone stop this…please stop this…” The obvious answer was that if Judy was violently hoping that someone else would stand up and do what she knew to be right, the tension would come from Judy realizing that she should do it herself but couldn’t. But how to make that believable? Why would she hesitate? Why would she think she should take responsibility?

I’d lived this scene over and over many times in my head over the years. I’d felt that it was because, although I knew Vietnam vets had been harassed versus thanked (as we would do today), this was the only time I’d seen it myself, and I shared the blame. Curiously, though the bones of the scene were based on reality, once I was into fiction I kept reaching outward and was stumped through many workshop drafts of how to make this scene—which I knew was fundamentally good—work.

Eventually, I had to uncomfortably put myself back into it, remembering what I’d been feeling personally, versus the bigger action of the scene. And, like Judy, I was reluctant to go there.

The vet was not the one we should be fighting, I remember wanting to yell, he’s what everything we’re doing is about. I knew I should stand up and tell them to stop; if ever there was a need for the confident voice of a leader, this was the moment.

But I faltered. I was afraid they wouldn’t listen to me, that they would even ridicule me. Why? Because I was a girl. Shamefully, I couldn’t muster the courage. I vividly remember the look of disdain on the vet’s face as he rose, turned, and walked out the door. My eyes followed his back. I felt…I felt like a coward. For the first time in my life.

I was a woman (a girl then) in a war situation where I couldn’t pull the trigger. That’s why this had been so hard to write. I’d stayed on the surface and kept myself from realizing why this scene had stayed with me. It was a mind-blowing (as we used to say) revelation. But digging this deep and painfully, I got my story. I understood that I wanted—needed—to write something that presented a female dilemma with the emotional intensity of the decisions facing the guys during that time.

The Fourteenth of September is about Private First Class Judy Talton, who is in college on a military scholarship in 1969 and has been having doubts about the war and her role in it. She risks future and family to secretly join the antiwar counterculture, and is ultimately forced to make a life-altering decision as fateful as that of any Lottery draftee.

—

Rita Dragonette is a former award-winning public relations executive turned author. Her debut novel, The Fourteenth of September, is a woman’s story of Vietnam which will be published this fall by She Writes Press. She is currently working on two other novels and a memoir in essays, all of which are based upon her interest in the impact of war on and through women as well as her transformative generation. She also regularly hosts literary salons to introduce new works to avid readers. www.ritadragonette.com

About The Fourteenth Of September

On September 14, 1969, Private First Class Judy Talton celebrates her nineteenth birthday by secretly joining the campus anti-Vietnam War movement. In doing so, she jeopardizes both the army scholarship that will secure her future and her relationship with her military family. But Judy’s doubts have escalated with the travesties of the war. Who is she if she stays in the army? What is she if she leaves?

On September 14, 1969, Private First Class Judy Talton celebrates her nineteenth birthday by secretly joining the campus anti-Vietnam War movement. In doing so, she jeopardizes both the army scholarship that will secure her future and her relationship with her military family. But Judy’s doubts have escalated with the travesties of the war. Who is she if she stays in the army? What is she if she leaves?

When the first date pulled in the Draft Lottery turns up as her birthday, she realizes that if she were a man, she’d have been Number One―off to Vietnam with an under-fire life expectancy of six seconds. The stakes become clear, propelling her toward a life-altering choice as fateful as that of any draftee.

The Fourteenth of September portrays a pivotal time at the peak of the Vietnam War through the rare perspective of a young woman, tracing her path of self-discovery and a “Coming of Conscience.” Judy’s story speaks to the poignant clash of young adulthood, early feminism, and war, offering an ageless inquiry into the domestic politics of protest when the world stops making sense.

Category: On Writing